Idealism vs Materialism

Let’s start again with a couple of quotes that should now sound familiar. The first is from Albert Einstein: “Space and time are modes by which we think, not conditions in which we live.”

The second comes from Ikhwan al-Sufa, an Arab philosopher who lived nearly 3,000 years before Einstein: “Space is a form abstracted from matter and exists only in consciousness.”

For the record, I didn’t pluck these quotes from my Grandma’s facebook page – they’re from a Stanford University website dedicated to Einstein and Gravity.

Stanford University will also be helping us define some philosophical concepts – thanks to their excellent Encyclopedia of Philosophy – – because we’re going to take a quick dive into “Idealism”.

Donald Hoffman is an Idealist. His Interface Theory of Perception (ITP) postulates that we interact with reality via the mental interface of our experience, which is being provided by our brain. This is pretty much a description of what’s known as : Epistemological Idealism. Defined by the Stanford Encyclopedia as follows:

“Everything that we can know about reality is presented to us by the mind”.

Everything we experience and know is a mental projection based on sense data and memory. Hopefully, after the last few chapters, this should no longer be a hazy concept – but no worries, we’re about to look at our relationship with reality once again from two different perspectives : philosophy and neurology.

So, are you a materialist or an idealist? Where do you stand, philosophically speaking?

Do you live in the real world of solid things separated by empty space? Are you and the world really as they appear to be? Or are you stuck in some fuzzy wuzzy mental projection? Are you and your world a product of your own imagination?

Obviously, it feels like the world we experience is real – we behave like materialists (or Realists, a similar worldview). But, spoiler alert! Despite materialism being the dominant consensus model of reality for the past century or so, even materialists must accept “epistemological idealism” and reject “naive realism”.

The naive notion that we always perceive life “out there” as it really is, doesn’t hold up. Because of visual illusions for example, or because the reality we see is nothing like what physics tells us. Or simply because we don’t all have the same experiences, and though we may all be wrong, we can’t all be right – especially when these experiences are contradictory.

And if we accept the current neurological model of consciousness – we’ll get to that in a bit – then we must accept that experience is mental.

If we accept that our experience of a material world is actually a mental state, does this mean that we can conclude that actual reality is fundamentally something mental? If my experience of reality is happening in my mind does this necessarily mean that the universe is made of mind, spirit, or pure consciousness?

No – that would be a huge (illogical) leap. Like a fish swimming in the sea who concludes that the whole universe must be made of water.

Nonetheless, I do get the impression some people are making that claim : that reality is fundamentally some sort of immaterial mind stuff.

These folks are ontological or metaphysical Idealists. They espouse what could be called Hard Idealism, as opposed to its softer cousin : Epistemological Idealism.

Before we explore the reasoning behind their worldview, let me just stick a pin where the main point of confusion arises :

When we say : “reality is fundamentally a mental construct” everything hinges on what we mean by “reality”.

Do we mean “what we see when we look at the world”? Or do we mean some fundamental hidden truth about the world that exists independently from us?As we look at the arguments, we need to keep this dichotomy in mind, in order to spot any sudden bait and switch between these two concepts.

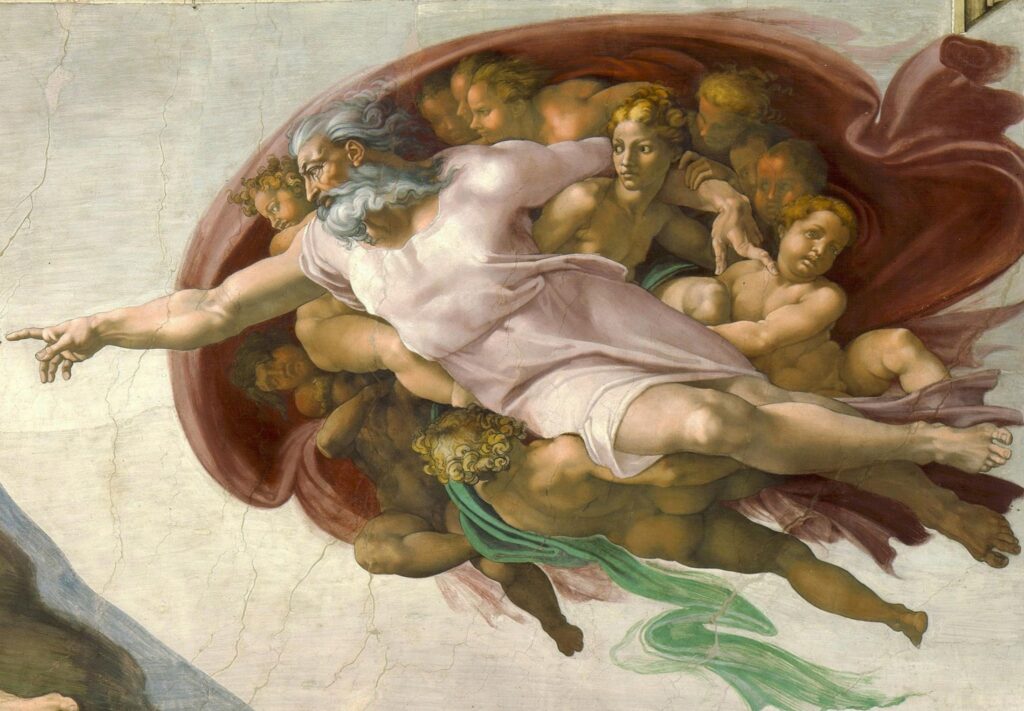

Insert God here

Maybe I’m poisoning the waters before we even dive in, so apologies, but there’s something else I’ve noticed about the people who identify as hardcore Idealists. They’re biased. Which doesn’t mean that Realism wins, because let’s face it : we all are.

We’re all born into a particular culture, and many of us on both sides of the realist vs idealist debate have been bathed in some version of Platonic idealism. This is the idea that matter is somehow less than its essence. Matter is somehow corrupted, less pure than its essence, which is some sort of ideal, perfect, timeless immaterial “form”.

We feel that our “spirit” or “soul” is who we really are. That our spirit is somehow superior, more essential than our material incarnation.

So when Idealists argue for the primacy of consciousness over matter, they are often defending a religious indoctrination. When they speak of consciousness as the “immaterial ground of existence”, they’re actually talking about God.

Donald Hoffman’s father was a Christian preacher of the fundamentalist, new Earth creationist flavor. So basically all in, a Bible literalist. Even if Donald struck out on his own, becoming a respected scientist, he was born into a world where God was ever present – at home, in school, in church. So when he insists that consciousness is in some way more fundamental than its contents – contents like spacetime and the objects we perceive for example – with nothing to back up his claim, I get suspicious. I’m thinking : presuppositions!

Since I’m sharing my suspicions rather than simply laying out the arguments – I might as well come clean : I can’t stand Bernardo Kastrup! Or at least I can’t bear listening to him or reading his stuff anymore.

Bernardo appeared on my radar as the prominent defender of modern idealism, and so I listened to him. I read his book of published papers : “The Idea of the World” – and slogged through it multiple times, mostly failing miserably to understand what he was on about.

Failure is painful, and so now I’ve become somewhat resistant to Mr. Kastrup. I’m suspicious of his cleverness, suspicious of his mysterious statements that remain mysterious however many times I try to engage with them. This of course may be entirely my fault – my difficulty comprehending complex math doesn’t mean that trigonometry is a load of nonsense.

Anyway, you have been warned. In spite of all that, I’m still going to present what little I have managed to grok from Kastrup’s book.

The Idea of the World

Bernardo begins helpfully by framing the materialist vs Idealist debate in two simple questions :

Are mind and matter polar opposites? Or does one arise from the other?

If we’ve never really explored this subject, these might seem like silly questions to ask. Are mind and matter opposites? We might say “of course they are! – that’s what we mean when we say those words”. Thoughts and ideas are not at all like hard solid objects.

But apparently thinking about this kind of stuff confuses the issue somewhat. It tips our familiar conclusions upside down – it challenges our normal experience.

Both sides in this debate actually agree that mind and matter are very much intertwined. Both assert that one arises from the other – that’s not where the disagreement lies. Materialists might insist that we have demonstrated extensively that consciousness is an emergent property of the brain. By fiddling with brains we can directly affect mental states. Idealists will reply : “it’s all in your mind dude – even your experiences and ideas about brains”.

Bernardo says : “we do not – and fundamentally cannot- know matter as confidently as we know mind”. By which he means that our experience of a material world is an inference based on our interpretation of sense data and memory. The “screen of perception” he calls it. Which sounds a lot like Hoffman’s mental Interface of perception.

“We cannot know matter as confidently as we know mind, because our knowledge of the world begins not with matter but with perception”. This is basically epistemological idealism.

The experiences we have of the world feel so real to us, that we confuse that experience for truth. When I stub my toe, the pain I feel is a hard solid fact. When I look at the sky, the blue I’m seeing seems to be happening “out there”. We can make accurate predictions about the world out there, we can navigate that world effectively. All of which creates the impression that we are directly perceiving reality. We forget that what we are directly perceiving is a mental experience.

In much the same way that we don’t usually realize we are dreaming when we’re dreaming – dreams feel real.

Materialism is basically the failure to understand that the material world is a cognitive construct. We interpret sense data, we are not directly perceiving reality as it is. Matter is an inference, thus mental – mind is the only certainty.

That last bit : “mind is the only certainty” is very much in line with Descartes’s : “cogito ergo sum”. Descartes’ statement being the finality of “radical doubt” – his conclusion being that the only thing of which we can be certain is the mental experience.

Anyway, the idealist concludes that what we call the “physical world” is more accurately defined as the “contents of consciousness”.

Obviously all that we can experience of reality is necessarily a mental state. But if an idealist is correct in asserting that we cannot be certain that the world is physical, on what basis can we assert that the totality of existence is exclusively mental?

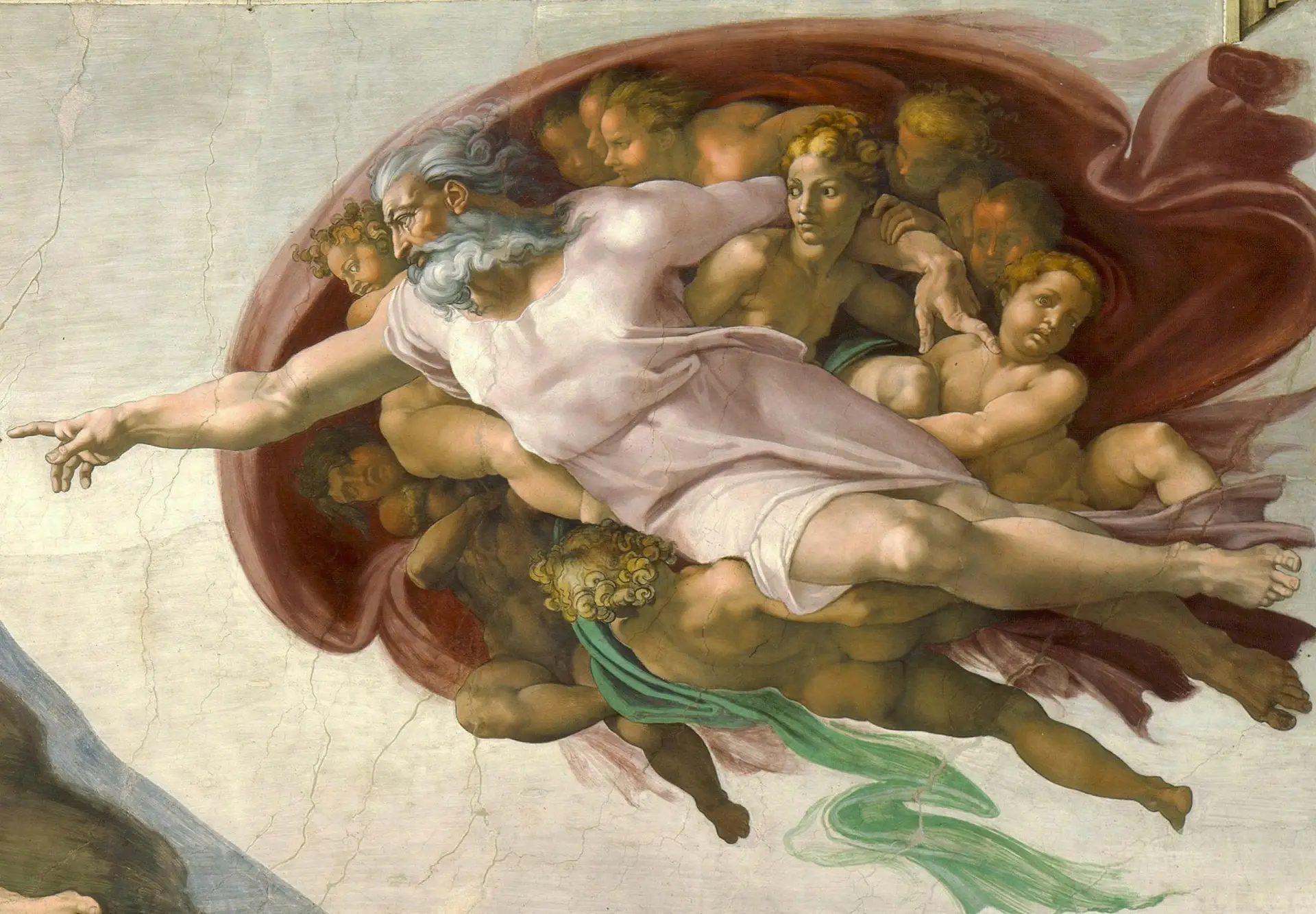

Bernardo does seem to assert that. He believes in a “universal mind” as the ground of all being. In his words : Universal mind is the “ontological primitive” (because he’s a philosophy guy) – which just means : that from which everything else arises, the source of the whole shebang.

He posits that reality is basically the expression of this universal mind, and that our subjective experience, our personal minds are like little pockets of consciousness. He believes that the one universal mind has somehow dissociated itself, and that this dissociation or segregation is responsible for all the seemingly separate identities that exist in the world.

Unfortunately, as I have already said, I don’t see why – I don’t see the logical steps or reasons that lead to his conclusion.

To back up his idea that our subjective experience is a dissociated bubble of the universal mind, he points to the mental health condition known as “Dissociative identity disorder” (DID). Which is just sad and troubling, and in no way an argument for his hypothesis – other than to say “hey! these things happen, it’s not impossible”.

As for his main reasons why we should believe that fundamental reality is necessarily mental, you’re going to have to ask him. As I said : I don’t get it – and I give up.

But let’s just end with some of the arguments that I did manage to grasp :

- If we were not conscious we wouldn’t even be able to deduce that there was a material world.

Our experience of the world is a mental state, and the material world is merely an inference within that mental state. So we can say stuff like : the mental state is fundamental, the material world is a secondary inference. At which point we are invited to commit one of 2 fallacies. The Definist fallacy, where we have used the word “fundamental” to describe our mental experience of the world – therefore Gotcha! fundamental reality is mental? Or the fallacy of composition, where we conclude that the whole of reality is mental because the only bit of reality I can be certain of is mental.

- If we accept the primacy of the mental state, and that the objects we experience are mental constructs – then to claim that consciousness emerges from matter is a supposition contrary to the fact.

Claiming that consciousness is an emergent property of the brain is wrong, because we can only be certain of consciousness ie. cogito ergo sum. Brains are merely part of the conceptual content of consciousness. Scientists demonstrating that human consciousness is tightly correlated to human brains are missing that important point.

The main problem with this argument is that it’s not an argument for anything – it’s an argument against the opposing camp at best. Unfortunately, even if we manage to prove conclusively that all Materialist claims are wrong, this does nothing to prove that Idealism is correct or even possible. For example, if you can prove that abiogenesis and the theory of evolution are wrong, we still cannot be certain that God did it.

- The observer principle (in quantum physics), which is about how a given situation is affected when we interact with it – via measurement or perception.

Bernardo presents this as an example of a spooky “mind over matter” event – as in the power of awareness or consciousness to transform material reality. But this is a rather personal interpretation on his part – and in no way representative of the scientific consensus. And even if we accept his definition as correct – then we would also have to take into account all the scientific demonstrations to the contrary. For example, how conscious experience is dependent on brain states – ie. that consciousness is determined by matter.

Bernardo also makes an argument from Jungian Archetypes. Which is about how our collective consciousness manifests in the material world. For example, our belief in concepts like money, or human rights, become actual objects in the real world as dollar bills or legislation. Make of that what you will.

At which point Dr. Kastrup feels comfortable enough, having shown that he is no fool, to sign off with a couple of religious statements that he feels are appropriate. So let’s just repeat them here :

“The world is the thought of God” Thomas Aquinas & “To see god is to be god” Sri Ramana Maharshi.

One response to “Idealism”

-

UteS

Hi Douglas, great topic, thank you.

The idea of introducing God as a kind of explanation for everything sounds kind of daring. Maybe it’s due to our authoritarian way of thinking?

Albert Einstein: “Space and time are modes by which we think, not conditions in which we live.”

What do we know about the circumstances of our lives without thinking, without knowledge, without theories about them? Is it not only through thinking (and what Krishnamurti called becoming) that the impression of time and space arises in the form of movement towards a goal, planning, past and future, from here to there?

We did not create our way of consciousness and thinking ourselves (how could we?), but it has developed over time like the rest of nature. This seems to be a phenomenon that, like everything else, seems to arise from nothing.

Leave a Reply