The Present is a record of the Past

When I first came across Joseph LeDoux’s book, The Four Realms, I wondered for a moment whether we were covering the same ground. For instance, this blog is an inquiry into the question of who we are, and his book is subtitled : A Theory of Being Human.

One way to define something is by describing its function. For example : what is a vase? Answer: it’s a decorative object often used to display flowers. Under this view, humans are simply primates that love to eat hamburgers and play video games; or who crave security and pleasure and making babies.

Another way to describe something is to identify the forces at play in its formation. Which is to say the object is the expression of the processes that cause it to be. A ceramic vase would be the result of the wet clay, the spin of the potter’s wheel, the desired image in the potter’s mind, the constraints exerted by the craftsman’s hand, the heat of the kiln etc..

Similarly, a Christian, thanks to their understanding of creation, can make the claim that our existence is a manifestation of God’s will

In both cases, the thing being described—whether a vase or a person—is understood through the dynamics that shaped it.

Professor LeDoux, like the Christian, is using the second method. He presents us with the dynamic processes that embody what we are. We don’t get to meet any hypothetical, invisible creator gods, instead we are taken on a journey. In this model we are the expression of life as it has been conditioned over deep time. We are the product of our evolutionary psychology.

LeDoux is a psychologist and neuroscientist. Like his colleague Anil Seth, he studies the measurable mechanisms of consciousness, rather than its metaphysical mysteries.

The “4 realms” of being human that he is proposing are : the biological, the neurological, the cognitive and experiential.

In other words we are living organisms with brains that conceptualise what we perceive – human consciousness is defined as our particular experience of those concepts. Consciousness is likened to a story we tell ourselves.

Evolutionary psychology is a school of thought that fascinates me. It resonates perfectly with my own worldview – which has been largely influenced by zen Buddhism and the work of J. Krishnamurti. Since these can easily be viewed as rather fuzzy philosophies, I am always on the lookout for scientific or scholarly validation.

Krishnamurti spoke often of the deep conditioning—biological and psychological—that shapes our behavior.

Buddhist teachings insist that our experience of selfhood is merely a sensation that arises from the interaction of the brain and our sensory apparatus.

This seems to reflect what “The Four Realms” is about : how we, or our beliefs, sensations, identity and attitudes are a cumulative expression of the past.

Of course, I’m aware that evolutionary psychology is not without its critics. It has, at times, been used to justify questionable claims or agendas. For instance, arguing that our natural tendency to cooperate means we should all be Communists, or that selfishness and jealousy are biologically ingrained and thus morally acceptable. These examples conflate descriptive facts with prescriptive ethics—a classic “is” from “ought” fallacy. Just because something is the case, doesn’t mean it should be.

It would also be a mistake to assume that humans are only affected by their genes or their basic instincts. We now have this behavioural force called culture. We could say : both genes and memes are driving our behaviour – and sometimes in opposing directions.

Anyway, as long as we accept that we are the result of natural selection, and that the brain has been conditioned by this process as much as the rest of the body, we’re good to go.

The feeling of being Me

Joseph LeDoux starts by considering what we call the self.

What do we mean by “me”? Are we an actual entity with agency? Or some kind of psychological phenomenon – more akin to a sensation?

The classical definition is something along the lines of : what I identify as being me, as opposed to the rest of the universe, which is not me. Dictionaries point to the characteristics or personality that are mine, that set me apart from everything else.

More precisely we could define it as our conscious, first person perspective. What it is like to be this highly precious, central agent looking out at the world. This experience includes an apparent constancy over time – I have the impression that I am, and have been the same me for as long as I can recall. It also includes an apparent division between myself and what I see – I, the observer, feel very different and separate from the stuff that I observe.

This basic sensation of being me is accompanied by a further sphere of existence that I see as somehow a part of me or as mine. My body for example is mine and in a way me at the same time. Likewise, possessions such as my house, my car or my achievements somehow determine who I am. My social status definitely seems to play a part in my self image. Finally my thoughts, beliefs and emotions seem to both define me and my relationships. I feel like it is me that is thinking the thoughts, but at the same time the thoughts have a certain authority over me and my actions and emotions and how I view reality.

In any case, this dynamic network or system of concepts and sensations mutually affects itself in such a way as to produce the feeling of being me. Our personality, how we present ourselves to the world, and the relationships we have, emerges from all these parts – the senses, the brain and its projections – working together.

What we are calling “me” then is not so much an independent agent hidden somewhere in the body, but rather this experience of selfhood – the persistent sensation that I am a central, autonomous subject around which reality revolves.

This impression that I am the main, most valuable character in the universe ultimately serves one essential purpose : survival.

Without a self there is no such thing as self-preservation or self-actualisation. Self-consciousness provides an extra emotional dimension to the biological imperative of replication, it adds to the fitness of our genes (so far, fingers crossed).

Without me, there can be no “I want” or “I don’t want”. And this dynamic of likes and dislikes, naturally inherent from birth, energizes our efforts towards security, pleasure and progress.

This mental, emotional and cognitive process we call the self is the psychological expression of being human. Our memories, thoughts, needs, choices etc are habitual, instinctive reactions or reflexes that arise naturally, often subconsciously, from the organisms that we are.

What our brain does is necessarily dependent on the type of brain it is : primate brains do primate type things, octopus brains do weird stuff etc.. We have human brains.

All types of brains are the result of a long evolutionary history. Ours behave similarly to those of other primates. And modern primates behave similarly to more ancient primates, whose inherited physiology and behavior came from their ancestors (ie. probably tiny lemur-like creatures).

And as we are the result of prior psychological and physiological conditioning, one could argue that we aren’t truly autonomous agents at all.

We do not choose how to feel or what to do, since we did not choose our evolutionary history. Every creature alive today has been conditioned naturally over time, either genetically or culturally, to act mechanically, or instinctively in certain ways. Just as rabbits don’t decide to be vegetarians, or Hindus don’t choose to picture some of their gods with blue skin – I don’t get to pick my next thoughts and wants. So hopefully that’s agency out the window.

We can of course still consider a person as an independent entity. This can be useful for communication purposes if we are describing some model or situation. But a person can just as easily be defined as a constituent of a larger organism, like for instance the society they form together, or the network of life on the planet, the biosphere.

Each organism or person can of course only be considered independent in a theoretical sense. In practical terms we only survive or arise as part of a larger process, or symbiotic relationship. Think sunlight, air, food, family, community—life is a network of dependencies, not a solo act.

Similarly, if we look down a microscope in the other direction and examine the constituent parts of our anatomy, like the cells, again the notion of independence fails. Science tells us that around half of the cells inhabiting our body, keeping us alive and healthy, are non-human – eg. indigenous bacteria, yeasts or protozoa. So not only is the so-called individual part of a larger ecosystem, it is itself a kind of walking, talking ecosystem.

Repetition and Recognition

The story of life and how it behaves starts with these tiny basic units : the cell.

They lay the foundation of our most basic driving force, our binary relationship with reality – which can simplistically be described as the movement towards good and away from bad. As stated in a previous chapter, our ancestors – ie. the primitive unicellular life forms that survived or the behaviour that was selected – moved towards sustenance and away from destruction. If they were attracted to hydrogen and repelled by ultraviolet light, and managed to reproduce, this motivational dynamic (of attraction and repulsion) was passed on.

Fast forward a few billion years down the evolutionary timeline to reptiles for instance, and this dynamic is still directing behavior, but now via nerves and muscles. Reptiles are said to react instinctively.

Another 100 million years later, mammals with brains awash in neurochemicals were able to graft emotions onto the basic momentum of repulsion and attraction. The extra impetus of feelings thus reinforcing and adding complexity to this successful binary dynamic, which we can now call : fear and desire.

The most recent addition to life’s basic existential preoccupation is the conceptual conscious experience. Stuff like thought, ideas, imagination, belief, memory. Homo sapiens being the undisputed champions by far of this new, and highly rare psychological realm of existence.

As we have already said elsewhere, conscious mental and emotional states are not the norm for living creatures.

The behavior of primitive animals, such as woodlice, crickets or moths, is affected directly by perception or sensation. If something essential stimulates the sense organs, a reflex action is provoked, without any need for some subjective cognitive experience. If sunlight is detected for example, I will immediately start crawling or flying in a particular direction despite having no idea or even any visual image of the sun, or light, or myself and the meaning of all my agitation.

Importantly, LeDoux reminds us that even among the few species with subjective experience, there is no shared sensory reality. Each organism lives in a different perceptual universe, shaped by its own sensory tools and neural architecture.

Bats and Tigers would not recognise each other’s perspective of the same environment.

And our perception of the world, and thus our attitude towards that world, also changes over time. These can be due to the normal physiological or hormonal alterations over an animal’s lifetime – eg. sexual development or parenthood.

How I relate to men, women, or infants is not the same now as it was when I was a child myself, or as a teenager.

Simple accumulation of experience also determines how subsequent events are interpreted. Memory of prior events conditions future experience. For example, my relationship with a 10 kilo dumbbell progresses as I work out at the gym. People who saw Jaws (the movie about a man-eating shark) early in life might never swim comfortably in the ocean again.

I can’t tell the difference between all the tonal variations in some Chinese languages – in the same way a Japanese person finds it difficult differentiating our L’s and R’s. There’s a huge correlation between familiarity and “normal”. Repetition and habit seems to dictate what feels correct and “true”.

This conceptual or cultural aspect of our relationship with reality is very modern and unique, and it adds seemingly endless complexity to our lives.

Our perception of “self” or the feeling of being me, introduces a psychological dimension to our existence. The relationship between subject and object is no longer driven only by primitive reflexes and sensations, but also by emotions and ideas about the interaction. We no longer just respond to stimuli—we respond to our conceptual images about the stimuli.

My behavior, faced with an ice cream for instance, is no longer merely based on yummy or not yummy, but also on my self-image. How I treat you depends a lot on our cultural identities : are you a Communist? Am I? What is your social status compared to mine? Are we part of the same tribe?

Complexity and choice

Although the world can seem more complicated due to all these, often contradictory, perspectives we hold, there are potential benefits.

The major one being : foresight. Our ability to build mental models helps simulate possible future outcomes.

The theory goes that our ability to anticipate allows for a more efficient use of energy. For example, based on spatial mapping or our visual memory of the local environment, we can forage in a predetermined manner rather than just aimlessly wandering around. Or we could decide to build up a storehouse of food in the event of some hypothetical future scarcity. We can plan.

The fact that we recognise and categorise things as independent entities with distinct characteristics was probably an essential part of the development of language. Because we saw the world as composed of distinct things, we created words—symbols to represent those things and their meanings. The theory being that language arises out of all the ideas we want to share. In order for language to evolve we first need something to say.

Anyway our communication became more precise, cooperation more sophisticated, and social bonds more resilient.

Overall, this conceptual and psychological existence seems to have been a huge success – in terms of fitness at least : we have gone forth and multiplied.

The vast proposition of complex choices that our brain can effortlessly concoct means that we exist in a space of huge potential and possibility. But with great opportunity comes the cost of great confusion, hesitation and the potential for really stupid choices. As Spiderman’s uncle once said : “With great power comes great responsibility”

Memory, motivation and meaning

Reality, for us humans, is inextricably linked to meaning. Things are inseparable from their conceptual significance – which is basically all the characteristics we associate with whatever that thing is. A tree for example has a species name, is made of wood and other stuff, is useful as lumber, gives shade and shelter to a host of other critters, has provided me and my kids with hours of fun etc, etc…

Hopefully it’s obvious that phenomena itself is void of intrinsic meaning – meaning is learnt. Meaning resides in memory.

Letters, numbers and cats for instance have no initial significance on their own – meaning is not in the object. If this isn’t obvious, keep in mind how the symbolism of any object changes across cultures and eras. Cats are sacred in ancient Egypt, companions in modern America. Cows are holy in some places, hamburgers in others. Clearly, meaning is fluid—shaped by context, not innate.

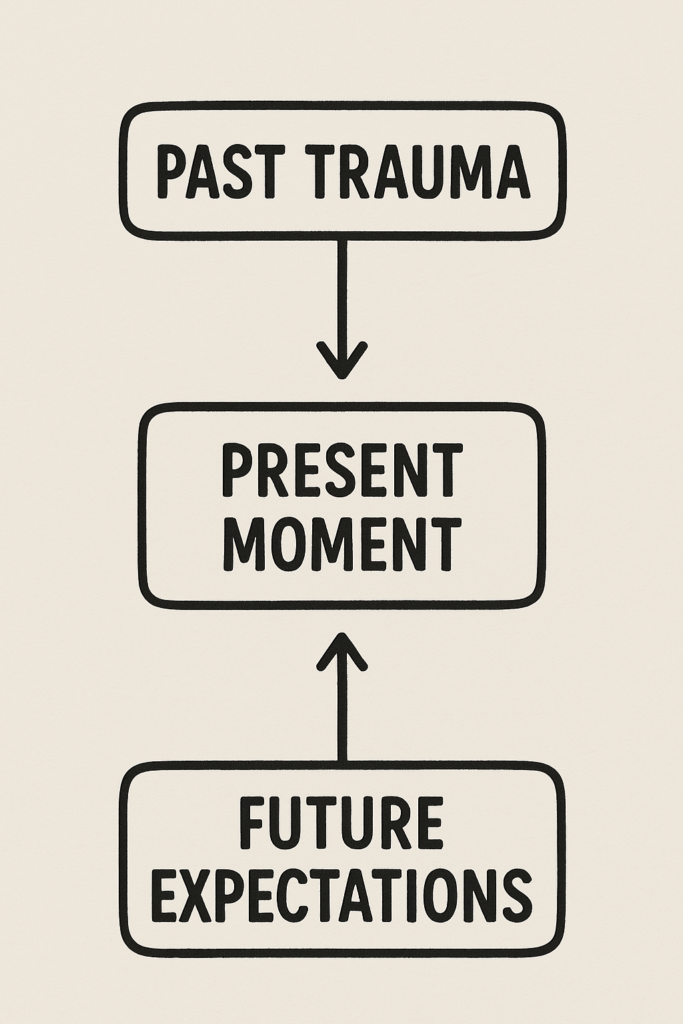

Therefore, since what we see is systematically colored by our prior educational conditioning – ie. viewed through a filter of cultural indoctrination – we can say that present experience is based on past experience. Expectation predetermines what we see.

Dwelling a moment on this issue of prediction and expectation, just to belabor the point about how time influences our relationship with reality : When Pr. Anil Seth calls the brain a “prediction machine” he is mainly referring to how prior events influence our perception of the present. But it goes further: our apprehension of each moment is also automatically colored by future expectations.

We mentioned earlier how our conceptual modelisation of our environment is ultimately a way of predicting beneficial outcomes.

Perceived phenomena, in other words : how we perceive ourselves and the world around us, is affected by both past impressions and future aspirations. Our worldview is the product of both trauma and ambition.

The world as a story

My brain is constantly and automatically judging and categorising the world based on memory. Everything my senses detect is immediately associated with past knowledge. Perception and interpretation seem to be inseparable. This is how we are presently defining consciousness, or the contents of consciousness, for humans at least. This is what it is like to be me : this moment to moment experience of the interplay between memory and phenomena.

Our brains are providing us with a narrative. This narrative, which is a story about the central character : me, having adventures in a universe full of secondary characters and concepts, is what we call reality.

Our experience of this reality is what we call consciousness.

This consciousness includes a huge psychological landscape that affects our everyday life. Our imagination, our feelings and beliefs about ourselves and others, the specific hopes and fears that this mix of mental content engenders. They all contribute to how we view our existence and shape the society we live in. Societies where the whole gamut of human behaviour plays out, in acts of friendship and invention, but also violence and segregation.

Anyway, the upshot is that our experience of the world is largely a conceptual construct. Consciousness is our experience of the meaning we project onto the world.

Consciousness is what it feels like to be this central character in the narrative we have built around ourselves – a neurological projection based on millenia of conditioning.

One response to “Evolutionary Psychology”

-

Does every living ‘thing’ have this feeling, sensation of ‘I am’? That apart from the ‘thing-ness’ of the physical: the body, the tree trunk, the fish, the insect, the flower, etc, etc…. there is this ‘I am’? Krishnamurti has suggested that that ‘I am’, ie., naked awareness, consciousness IS what we are. Not a ‘thing’ at all. No-thing. That the big-brained human thinking himself/herself to be an ‘individual’ was a result of identification with his/her thing-ness? A turn in a wrong direction? Unfortunate for us because ‘becoming’ more, which was / is necessary to the brain for its need for security, meant maintaining and burnishing this image of an ‘individual self, at the same time keeping itself in the past and projecting itself through the present and into a psychological imaginary future and keeping itself from a potential ‘blossoming’.

Enjoyed reading your work Doug and look forward to rereading the first two.

Leave a Reply