Complexity vs Confusion

“Philosophers have only interpreted the world… The point however is to change it” (inscribed on the grave of) Karl Marx.

I’m going to agree with the sentiment. It resonates pretty well with what an understanding of the world entails : we act in accordance with our deeply held beliefs; the societies we create are a reflection of who we are. I’m more concerned with our actual responsibilities and well-being, and less interested in debates that seem too far removed from our shared reality.

What we are exploring here would be more akin to ethics and existential clarity than metaphysics. We’ve been looking at what it means to live a good life and why we keep failing to do so; and not so much wondering about the exact details of fundamental reality, the size and shape of souls, or other stuff slightly beyond our ability to address meaningfully.

That said, I’m not a Marxist – and changing the world, rather than merely interpreting it has arguably led to massive harm, as demonstrated by Marxist revolutionaries worldwide. So what gives? Where’s the glitch?

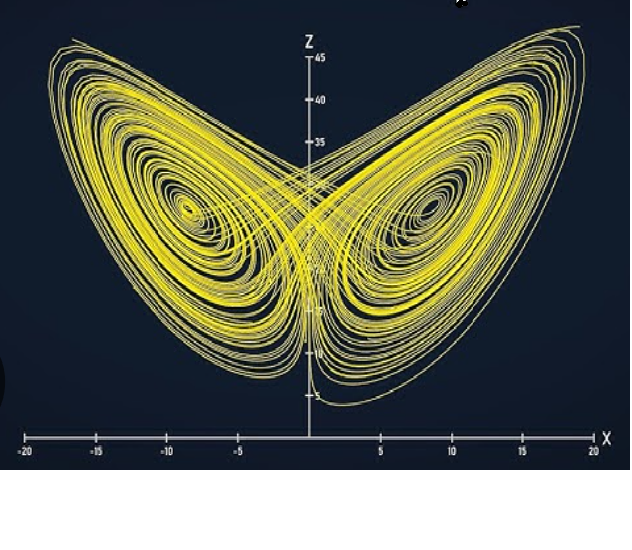

We could say that everything is overdetermined : hurricanes in Florida aren’t just caused by a chaos butterfly flapping its wings in the Amazon. There are a huge array of different correlated phenomena, like the interactions between the sea and the sun, that are all playing a part in the process. Thus any action based on incomplete – or erroneous – information, could so easily backfire.

For example, killing butterflies in the Amazon will certainly affect the local ecosystem, but it probably won’t impact the tropical cyclone situation one bit. Blocking out the sun or drying up the ocean might work better, but catastrophic outcomes tend to be considered a fail when problem solving.

When it comes to revolutionaries trying to impose the “good” (i.e. the utopian political structure) by whatever means necessary, we also have to address the issue of violence as a strategy.

Forcing our worldview onto others – especially if it’s wrong or incomplete – is basically just a form of bullying. It’s a bad start and there’s no reason it should end well either.

We can say : violence + confusion = bad. Violence and confusion, as a way of achieving potential future “goods”, are ineffective, even counterproductive.

That the means of production are being controlled by a small number of rich people might be a fact. Capitalism may also be a self-perpetuating cause of systemic inequality. And thus it may logically follow that equality can be achieved by elimination of the wealthy. However it does not follow that we should immediately start forcing our preconceived dogma down everyone’s throats.

Logic is a great tool for avoiding nonsense, but it cannot guarantee outcomes in the real world. Ideas need to survive confrontation with the world, they need to be tested before being accepted as accurate.

And three simple ideas about wealth, equality and the means of production are far from a complete picture of our economic interactions. Our lives seem to be enmeshed in a complex web of interdependence. True isolation doesn’t seem to be a viable option.

So before throwing out the capitalist bathwater we might want to explore our basic concepts further : how deep is our understanding of wealth and inequality? How is wealth being created? Is it a zero sum game? Do I have any biases? What does the actual data show? Have I considered how psychology and fear drive both greed and reform? etc. Maybe we could start with some practical experiments – rather than behaving as if our subjective takes on Marxism were gospel?

So there’s the degree to which our theories accurately reflect the world, and the extent to which the effect of our actions ripple out into different areas of our lives. But there is the further question of whether we are actually addressing root causes. If we are only dealing with symptoms at a surface level – it’s probably because we’re unaware of or reluctant to face the core issues. If we’re constantly getting headaches we should find out why, rather than relying solely on Aspirin.

The Structure of Society

Laws and institutions that regulate societal interactions may well be of practical necessity, but the reason I avoid trespassing for example, is due to my own inner narrative. It may be due to a form of cultural conditioning, which may be shared, but which has become part of my personal psyche. Like putting on my seatbelt, saying hello, or when to cross the street : no police necessary. I’ve already got a tiny supreme court judge living in my head.

Society functions thanks to the attitudes and behavior of its constituents, the citizens – there just aren’t enough police to go around.

Marxist ideology is an attempt to solve our problems by reworking the structure of society. But no matter how lovely the architecture or how clever the engineering, we cannot afford to ignore the quality of the raw materials. In other words : us and our deep seated drives. Our behavior determines outcomes, at least as much as the political and economic infrastructure. It’s people who will be pulling the levers of the guillotine. It’s people who will make up the cheering crowds. It’s people who will be the new bureaucrats in utopia.

When Capitalism is keeping profits high and wages low, or undermining workers rights – how much of this is a result of the economic system, and how much is due to base human psychology? And by tinkering with our political and social structures, does this in any way affect our deep seated motivations of fear and greed?

Even as we try to regulate the worst of human behavior by social engineering, we have to recognise that society is an expression of its people, and that we are motivated by our psychology. So any effective transformation of society, whether from the top down by changes in legislation, or from the grassroots, via an evolution in the minds of its citizens, requires a clear picture of those psychological processes.

Religion, Philosophy & Therapy

It might help if we consider 3 different ways in which we have historically tried to make sense of our place in the universe : Religion, Philosophy and Psychotherapy.

What we call religion, perhaps the most primitive (or primal) of the lot, might also be the most ambitious. It provides an immediate and complete response to the totality of life’s inevitable lot of meaningless struggles. Meaningless in that all our efforts inevitably end in failure (i.e. death), with the only potential consolation being that we pass the torch on to those that remain (i.e. future generations).

The absurdity of life is resolved through the contemplation of some “higher power”. By virtue of a “relationship with God” or a sense of “unity with the divine”, the suffering is dissolved. God provides a Christian with the means to temporarily unburden themselves of their mundane anxieties. Their insurmountable problems can be viewed as something tiny now in the care of the all powerful mystery. The absurdity of existence as this tiny struggling self disappears as we surrender and disappear into the divine.

That kind of spiritual mumbo jumbo not making any sense? Maybe you’re a philosopher.

A philosopher being someone trying to get to grips with the world by getting to grips with the best ideas, or best ways of thinking about the world. Best usually meaning most reasonable. Are we just spouting meaningless nonsense? What do we mean by self? What do we mean by the divine? What does it mean to be in a relationship with a mystery?

The highest power in this field of inquiry is rational thought. Which allows us to ask the question of how wisdom is related to thought. Does living the “good life” mean having the best ideas?

The answer to this question might become apparent if we look at the current state of the discipline after thousands of years of debate. Nothing appears to have been definitively solved. We still aren’t quite sure about what’s going on.

So : No. Winning in philosophy does not mean “having the best ideas”. Finally coming to conclusions about the “ultimate truth” would be the death of philosophy.

So maybe the “best way of thinking” is to not let thought become a barrier to discovery. If we want to continue as philosophers we must be careful not to allow too many conclusions to crystallise into dogma. We must not let ideas be our prisons.

The third method mentioned was Psychotherapy. This refers to a variety of ways of dealing with the mental and emotional aspects of trauma. A whole array of proposed solutions including drugs, visualisation, analysis and even simply providing friendly, safe human relationships – all in the hope of beneficially influencing our attitudes and behavior.

Its main value lies in its availability as a way of addressing emergencies – in the case of mental breakdowns and burnouts – when a loving hug is either insufficient or unavailable. Although these days some forms of “humanistic” therapies aim to develop the “full potential of self” – whatever that means – so not just dealing with burnout.

Therapeutic methods of mitigating harm; a religious mindset that allows us respite from the human condition; and a brain that remains spontaneous and adaptable, rather than becoming petrified by its own thought. These are definitely most excellent!

And if these practices could somehow allow us to act more intelligently and compassionately – even more excellent!

Of course there are inherent dangers with depending on thought and narrative, be it the Christian narrative, or on any narrative, be they Marxist, Hindu, Buddhist or Jungian.

The danger of conflict for one, when contradictory dogmas come into contact with each other. The danger of being bound by certain ideas, and thus missing out on anything outside the confines of our adopted narrative. All of which pretty much cuts us off from compassionate and intelligent action.

Dogma is a barrier to discovery.

We are so easily led down a path of rational conclusions and behaviors that seem convincing based merely on consistency within a particular, narrow model. If this is true, then it follows that this is true, and therefore this next thing must also be correct. And before we know it we’ve become bloodyminded and righteous – forgetting the all important if at the beginning of our intellectual and emotional journey.

Here’s a “rule” that might be helpful : information or data is only potentially practical in so much as it accomplishes some goal.

Models or beliefs, if at all useful, are necessarily contextual. They cannot be a reflection of every moment, because the current “truth of the matter” is never static.

Without an understanding of our motivations and blindspots, despite genuine goodwill, we have no way of evaluating our progress. No way of knowing if we’re heading towards or away from the cliff edge.

Like a child who knows nothing about the metabolic effects of sugar trying to judge what best to do with a ton of sweets. The same way a toddler pricked with a needle for a vaccine might come to the wrong conclusions about their doctor.

As promised, we will be looking at some ways that these issues have been addressed. Three to be precise : the work of David Bohm, Jiddu Krishnamurti and the zen school of Buddhism. Admittedly because they have been a part of my life for as long as I can remember, but more importantly because they are simple, practical and potentially revolutionary.

Not revolutionary in a political sense, more in terms of revolutionising our relationship with reality – freeing each of us from our own delusions and shackles.

Also it might seem strange to call these teachings simple, especially when faced with seemingly illogical and incomprehensible zen riddles. Or the puzzled faces of the audience at a Krishnamurti talk.

By simple I mean in terms of their focus on a single point : our experience of reality. And the simple practice of how one might understand and address the problems of our relationship with reality : namely via care and attention towards our lived experience.

It’s simple in the sense that an honest appreciation of our own everyday existence is all that is necessary; there’s no need for specialist knowledge. Nor are there any hidden phenomena or complex concepts that need to be uncovered and unravelled before the inner revolution can take place.

Any difficulties we might have when grappling with notions of selfhood are probably due to a lack of familiarity with ourselves. Which is a weird thing to say considering how often we are ourselves. However I’m rarely curious about being me – all my attention is taken up by what I want. Our eyes are on the prize, we are constantly preoccupied with fulfilling our needs, with hardly any curiosity towards the hole that needs to be filled.

We also struggle with new ideas when they clash with beliefs we’ve already accepted as true. A form of intellectual and emotional resistance comes between us and the threat to our current worldview that these new ideas represent.

Simone Weil

Reading up on the history of philosophy and religion as I have recently (for this blog), I came across a couple of things that may or may not be helpful, but are related to what we’re discussing here. So before we get into David Bohm, whom I’ll be presenting in the next chapter, let me tell you a story :

Once upon a time there was a little jewish girl named Simone Weil. She grew up to become a famous French philosopher despite dying aged 34 during World War 2. Not only did she die young, but she hardly published anything whilst she was alive – yet there she is, cited in nearly every list of notable modern thinkers (at least in France anyway).

Her notoriety seems largely due to how she lived : as an outstanding example of integrity.

She famously denied that philosophy was all about acquiring knowledge or constantly refining our theories. But rather that it meant living in truth; that there be no separation between truth and action.

Already at university, in order to align with her beliefs about education and democracy, she organises her fellow students into a Social Education Club. The group basically spends its weekends giving free classes in French, Maths, Physics and Social Ethics in poor neighbourhoods.

When for a short period she becomes a big fan of Marxist theory, she gives up her job as a teacher to go work in a factory.

During the Spanish Civil war her Pacifist and Anarchist convictions prompt her to travel to Spain and volunteer – she ends up fighting to save the lives of prisoners of war.

She is taken to hospital in London in 1943, suffering from Tuberculosis. Exhausted by her work for the French Resistance, weakened by her refusal to eat in solidarity with everyone back in France under Nazi occupation, she dies shortly afterwards.

Her self-sacrifice was astonishing. Reading about her in the Big Dictionary of Philosophy at the local library, I might even have shed a tear. Which is probably the first time I’ve cried over a Dictionary.

Speaking of sacrifice : she is also considered by many to be a Christian mystic. She wrote extensively on religion, and had various mystical insights or religious experiences. But refused to convert, preferring to live her love of Christ freely, outside of any Church. (This is similar to her politics, refusing to become a member of the Communist party – and subsequently one of the first to point out the flaw in rule by bureaucracy)

Anyway, her writing is published posthumously. Other, more famous philosophers look at her and go “wow!” But the question arises : was she a genius, a mystic? Or living in cloud-cuckoo-land? Or a bit of both maybe?

Yes, she scaled intellectual heights with ease, over a wide range of topics : in the philosophies of religion, science and politics. Her intellectual honesty and fearlessness in thought and deed were astounding and rare.

But wasn’t her death a bit dumb? Couldn’t she have achieved more by staying alive?

Maybe my questions are missing the mark. It’s hard to judge the inner life of other people. Perhaps a life is better judged by its brilliance than by its length – could Jesus have achieved more by staying alive? Is an existence lived fully not worth living?

Would more self-concern and fear have led to a better life?

Is it possible to live an honest life of care? Simone Weil indicates that it might.

Was she being true to a bunch of ideas? Or was she fearless and caring enough to allow for all insights? We cannot know her mind. Can we know our own?

6 responses to “Change without Carnage”

-

Adeen

Krishnamurti comes closest to psychotherapy, but for Krishnamurti thought or analysis is not the right tool to experience what he says. In that sense he is completely experiential and not ideational. As he negates thought as a tool, what he is saying cannot be converted to an idea to be implemented within the structure of thought. Thought or analysis creates division and also leaves a psychological mark on the brain. The division creates conflict as me and the other, thinker and thought, observer and observed image. It is the self or sense of me. It has created the ego identity that divides itself from the rest of the world and therefore is responsible for all the conflicts in the world. To go beyond oneself is not an act of thought. If thought as a tool of the brain is not active then mental division ends. Then there is space for everything to flow. The space has no me. You can call it choiceless awareness, awareness without sense of me. It is not part of conditioning and leaves no psychological mark on the brain. It is liberation or freedom. So Krishnamurti is completely experiential and not ideational. Now what brings about the step where thought as a tool is no longer active? It is completely experiential, so direct living and experiment reveals this. Krishnamurti might be a pointer, but the experiencing happens directly. As he says the word freedom is not freedom.

-

macdougdoug

Thanks Adeen – trying to describe what’s special about these teachings or practices (ie. zen, dialogue & Krishnamurti) is definitely something worth getting into – it’s been on my mind a lot lately – K talks about the religious mind, but rejects religion; He says meditation is essential, but rejects any traditonal methods. And keeps pointing at the mechanical workings of our psyche for sure. Contemplative, Transformative Philosophy of Awareness ?

-

UteS

“It’s simple in the sense that an honest appreciation of our own everyday existence is all that is necessary; there’s no need for specialist knowledge. Nor are there any hidden phenomena or complex concepts that need to be uncovered and unravelled before the inner revolution can take place.”

It is quite astonishing that only Krishnamurti, Bohm, and Zen Buddhists have identified thought as a cause of our contradictory and conflict-ridden way of life.

I didn’t even realize that I was constantly thinking until I tried to stop (this will probably also happen to people who start meditating in the conventional sense).

Reading Krishnamurti and Bohm, the whole dimension of thinking opened up, in particular the creation of a kind of reality that one considers to be actual, objective or undoubtedly real. Without realizing that it is based on thinking in the form of evaluation, comparison, personal or social standards. What I see seems to be what I think about it. This part may be experienced – to notice that you have prejudices, for instance.

The further dimension is Krishnamurti’s statement that the thinker is thought, which contradicts the feeling that it is me, the thinker, who applies and controls thought – I myself as a construct of thought, or even just as a momentary thought passing through the brain, generating feelings…somehow that seems to be the case? -

macdougdoug

The effect of identity and identification on our behavior is powerful – that much at least can be seen I reckon. And thats already great. Seeing through the whole illusion of self is a lot to ask of us poor humans.

-

Adeen

Just to see that thought is not the way forward, I feel brings about a transformation. No matter what feeling or thought arises both in me and outside as expressed as others, if thought is not the way forward, there is no reaction as thought to it but just choiceless awareness of whatever is happening without further reaction as thought. That way thinker which is just a reaction of thought is eliminated. This silent choiceless awareness is just passively aware without thought reaction. That awareness is sensitive, unconditioned and reveals what is happening

-

macdougdoug

Yes, to see that our relationship to thought was problematic does sound potentially transformative. I always wonder though if there is anything we can do in order to come to a point where our understanding of the problem of self or thought becomes unavoidable. It seems that there’s a whole network of causes and conditions that are needed to bring about a choiceless revulsion towards the pettiness of self-concern.

-

Leave a Reply