Let’s imagine you were stranded on a desert island.

You’ve made a little shelter for the night, you’ve managed to gather some food, you’ve sharpened a stick to keep the beasts at bay. The thing to do now of course would be to light a little fire.

We definitely know how to do that : we’ve all read the books, and even watched the chaps on reality TV rubbing sticks together for hours on end. Hours and hours of rubbing – the chafed hands, the aching muscles – but oftentimes, not even a whiff of smoke. There are people that can do it easily – a few seconds with some twigs and presto! Fire. These would however be people with know-how, born and bred in the bush, or trained adventurers. For most of us, even though we have a rough idea of the techniques involved, the task of lighting a fire with just a couple of sticks would be near impossible.

So my question is : How on earth did anyone come up with this incredible idea?

Presumably someone invented this procedure. Top marks to them! This strikes me as quasi-miraculous – and I’m not the only one: see Prometheus’ story (nb. the guy who stole the secret of fire from the Greek gods).

In my mind, Einstein’s got nothing on our first anonymous fire starter. The God of genius must have somehow been involved.

With my cultural bias and modern-day IQ, I can relate to young Albert grappling with scenes of naive occupants in a falling elevator. This is probably because Albert and I are, as they say, standing on the shoulders of giants – I may not really understand the meaning of E=MC2, but I get the idea of stuff like cause and effect, narrative or logic.

Our prehistoric genius however, was stranded in a wilderness where fire only appeared as if by magic. Technology, for the last million years, consisted of banging rocks together in order to squash stuff. What happened was obviously not due to intelligence as we tend to quantify it: we’re not talking about IQ. Logic, reason or a vast library of technical knowledge won’t help us here.

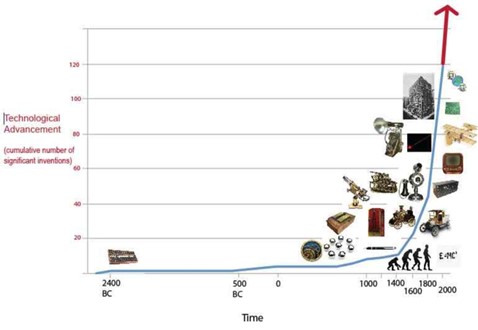

Sticks + Friction = Heat. Heat + combustible + oxidant … Forget it. (Innovation, discovery as a concept only really began to take off in the 16th century)

Our prehistoric inventor was obviously some kind of demigod, blessed with incredible powers of vision, clarity and pure creativity.

I would like to describe this scenario again if I may: Our ancestors liked to burn things. It makes stuff taste yummy, it keeps us warm, we can see in the dark, we can stare into it for hours – all this fantastic stuff and probably more. What more do you want you might ask – it makes life worth living and some say that it fundamentally changed who we were and the planet we lived on. That it may have led to the development of the modern human brain, thanks to the extra nutrients from easily digestible cooked food, sounds like a tenable hypothesis. (Some anthropologists posit the hypothesis whereby big brains started to develop in areas with access to volcanic activity) That it changed our internal microbiome, and at the same time the environment we lived in – due to the resulting population explosion from all that good food and people setting fire to stuff all the time – sounds completely legit.

So we generally agreed that fire was great. It was probably part of the Prehistoric mindset, along with food, sex, itching and wild animals. The ability to control and handle fire was certainly part of everyone’s skillset, local taboos notwithstanding. Finding fire, caused by lightning, would have been a thing. Transporting it back to camp and keeping it going, another thing.

But wanting to be able to start a fire from scratch, was that a thing? If so, this means that we’re going to have to assume a few characteristics about our hypothetical protagonists. Like for example that they were modern homo sapiens with a brain similar to ours. I say this because these bad boys (and girls etc.) were going to have to imagine something abstract, something that did not exist. And not only that, but to imagine that creating some non-existent thing, at a time when no one was doing stuff like that, was even possible.

Serendipitous Exaptation

Anyway, the most popular, or obvious answer to the fire question: “How did we discover that we could start a fire by rubbing sticks together?” is Serendipitous Exaptation. That’s a fancy expression (I may have just made up) which means discovering something accidentally thanks to an invention meant for something else.

The word Exaptation is used when biologists talk about the evolution of things like feathers. This is due to the theory that feathers did not initially evolve because they were so useful for flying – but rather that they were initially useful just for showing off (for sex and fighting) and for keeping warm. The first feathered creatures did not fly – and they only further evolved into proper flying feathers when crazy jumping and gliding creatures found that they were really practical for the long, long-distance jumps. Exaptation is a bit like adaptation, except that instead of just getting improved upon, it gets used for something completely different.

The claim is that people did not decide to rub bits of wood together because they thought that it would start a fire – they were rubbing bits of wood together for a totally different reason: maybe they were drilling holes.

Sometimes we need holes. And a good way of making holes in stuff is to use a sharp pointy, hard thing and shove and twist it into a softer thing – like a big thorn or a big bone fragment that could be used to puncture some animal hide. In this case, we need a hole in a piece of soft, pliable wood. The best way of making one back then would be to use a pointy stick of harder wood. (Because you didn’t happen to have a pointy rock or some pointy bits of ivory) You can make pointy sticks yourself.

Anyway, once you get really good at rubbing bits of wood together in order to drill holes, you notice the unmistakable signs of fire – the familiar smell, the charring, the smoke – and seeing as rekindling fires from embers every morning has always been part of your life: you know what to do. From urgent need and familiarity, you have managed to start a revolution that humanity and the planet are still feeling today. From desire and clarity, you have uncovered and mastered the unknowable.

Gaïa’s mentation

Stuff happens. Change is happening all the time, we all participate in moving things along. But sometimes we can point at the main instigators and say: “Look at them! Stirring stuff up.” Like the ones that rustled up all the planet’s oxygen; or the ones that killed off all the dinosaurs (cyanobacteria and asteroids).

Us humans have been the main instigators of planetary change for a while now. Anthropocene is what we have named the human epoch – so we are well aware who’s in charge – and for the first time the Biosphere might well be in the hands of a self-conscious pilot – we just want to know: In charge maybe, but are we in control?

If we are going to be the planet’s eyes, ears, hands and brains from now on – this is a huge game changer – a huge promotion. If we are going to rise to the task in a competent fashion – this will call for a revolution in humanity’s identity and the shouldering of great responsibility.

The driving desire as always, is still survival and wellbeing – no worries there – the question is whether we are sufficiently malleable and pragmatic for this psychological evolution? As our destiny is to become Gaïa’s mentation – can we still afford to be worrying about whose alternative facts we should believe? As we are being called upon to form the Noosphere, to function as an integral part of a superorganism (ie. Planet Earth) – can we still afford to react from self-centered confusion and conflict?

A change is a gonna come, always has done – no doubt there. The only question is whether humanity is going to be around to participate in that change, and if so, are we going to do so driven by fear and confusion, or with clarity and acceptance?

Just to be clear, I’m not only talking about reason and logic. Luckily, smart people exist – and we can put them in school to make Cosmologists, Astrophysicists, Meteorologists, Biologists etc. Thank God for smart people – if only for the invention of the washing machine and running water. (And all the yummy food, hospitals, and not dying all the time etc. etc.…) I also like that we have been to the moon, and even checked out our dead neighbors : Mars and Venus.

These people are, of course, essential. They can give us a heads up on what happens, for example, when we press this button, or when we acidify that ocean. They might even invent our replacements: an AI smarter than us.

What I’m talking about is fulfilling our potential. We have been blessed with an unparalleled capacity for shared imagination and belief. This can lead to amazing creativity like discovering how to control fire, or to splice genes. It can also lead to believing in demonstrably fallacious and harmful stuff (insert your own example here).

I would like to inquire into how this all works. What inhibits clarity, and why we fall prey to confusion? What are the traps and pitfalls that lead us astray from our human potential?

2 Responses

COMMENT DIABLE QUELQU’UN A-T-IL EU CETTE IDÉE INCROYABLE ?

Propositions:

– et si tout d’abord, personne n’a EU cette idée? Si l’humain n’était pas la source des idées, mais plutôt son réceptacle?

– et si frotter ensemble deux morceaux de bois ( si le principe de la friction ) n’était qu’une “propriété naturelle” de cette dimension; au même titre que la gravité par exemple? Car dès lors où il y a densité et loi d’attraction/répulsion, comment échapper à la friction?

– et enfin, si le feu était la “manifestation physique” de notre part spirituelle? Car le feu n’est-il pas soumis à la gravité, l’attraction terrestre, comme tout en ce bas monde? Et pourtant sa flamme se dresse irrémédiablement à la verticale à l’inverse de la loi implacable de la gravité, vers l’infini…

Salut Is a bell,

L’hypothèse est bien que la découverte dépend de l’observation des phénomènes physiques (la combustion du bois par frottements dû à des activités distinctes de la volonté de faire du feu).

Si j’ai bien compris votre proposition : que les idées existent en dehors de notre cerveau, et que nous ne faisons que les capter. Ma première question serait : est ce que l’ensemble de ces idées (dans l’éther) est constitué des idées fausses comme des vraies? Et comment expliquez vous le fait que nos idées/croyances changent en correspondances avec la culture/société dans le temps?

Finalement, je dirait que soit tout est manifestation du divin, soit rien ne l’est – les différentes relations que les choses ont avec la gravité nonobstant.