Navigating narrative

The stories I believe can be shown to be correct, we can use them to make accurate predictions. That’s what the scientific method is all about : testable models. Definitely a huge win if we don’t want to be completely wrong.

But I’m not a Cosmologist, nor am I a Theoretical Physicist – and when presented with a model of how gravity works for instance, I’m being told a story. And in such my biological, or my psychological conditioning is exactly the same as that of my ancestors. None of us can ignore our evolutionary history. My brain produces an image of reality instinctively from the concepts presented. If it’s the classical Newtonian model of gravity taught in elementary school, I’ll probably conclude that gravity is a force acting at a distance, that planets are a bit like magnets.

Nowadays of course, thanks to Einstein’s model of spacetime, I’m imagining (as best I can) giant bowling balls moving around some sort of invisible multidimensional trampoline.

Something we’re all probably familiar with is the problem of Quantum. When Mr. Everyman is presented with concepts like quantum non-locality or Schrödinger’s superpositioned cat, opinions will instinctively be formed, conclusions will be made.

Gary vs. Fritjof

My go to example to illustrate this point is Gary Zukav. Gary wrote a most excellent book in 1979 called “The Dancing Wu Li Masters” in order to popularize the findings of modern physics. Forty years on, and Gary has become Oprah Winfrey’s favorite spiritual guru. Thanks to his understanding of quantum phenomena he now encourages us to engage in telepathic communication with Dolphins.

I’m going to go out on a limb here, but I’m pretty sure that nothing in Shrödinger’s time dependent equation : E=p22m+U(x,t) or anything similar, justifiably entails Dolphins or telepathy. But our brains are capable of making those epistemic leaps, apparently with the utmost ease. Our senses and our brains naturally lead us to make conclusions, from which we can further refine our experience of “reality”.

Fritjof Capra, is another author who wrote pretty much the same book, the 1975 bestseller : “The Tao of Physics”. His understanding of quantum phenomena never subsequently led anywhere near aquatic mammals. Mostly he stuck to boring stuff like encouraging a more holistic approach to Urban Planning and research into Ecology and Systems theory.

Zukav and Capra seem to be living in different realities. We are born into a world filled with stories. These stories condition our understanding and inform our actions – we look out at the world through a filter of knowledge. Gary for example was born in Texas and studied politics and sociology at Harvard. His life story gave him a different lens from Frijof, an Austrian who studied theoretical physics.

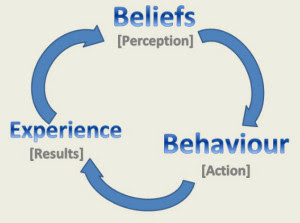

We are caught in a cycle of belief that affects what we see. A cycle because what we see confirms, and further conditions our beliefs.

Parochial vs. Universal explanations

Our tribe has become increasingly global, we are no longer hunters or farmers, our culture has changed : we call it industrialized, scientific. Logic and reason have caused a revolution in the stories that we tell each other. Once upon a time, in order to explain the world, all we had was our personal, subjective experience. We thought that the sun, the sky and the stars functioned like me and my kin. That the gods were just very powerful versions of us. That they pulled the sun across the sky or threw lightning bolts, for the same reasons we would, because they were angry, jealous or sad.

Now we aim for Universal explanations : models of reality that remain constant, irrespective of my personal opinion or tribal traditions. Models that remain correct and demonstrably so, whether we are on Earth or whizzing past Alpha Centauri. Which is great if we prefer beliefs that align as much as possible with actual reality. The stories may have changed, but I still have the same human brain. The cultural environment has evolved, and thus we have had to adapt the characters and forces at play within the narrative, but we continue to react to the stories in the same instinctive manner. Our evolutionary psychology is still at play.

The Map vs. the Milieu

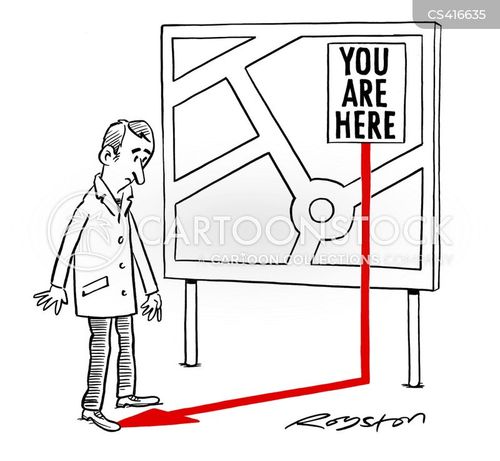

Which means that I still apprehend the world based on my story, my “reality”. Thus, whatever I see, whatever you say, will be a version of what I know. In a sense, we could say that I am not directly interacting with the world, rather I am interacting with my idea of the world. It’s a bit like using a map, a map which also includes myself – so it’s more of a GPS map where I am being represented by the tiny car.

This implies that my everyday experience always involves a challenge : the challenge of making the map coincide with actual reality, aka the territory. We may not always be aware of this conflict, but it is just a fact about maps.

This can become especially challenging when we try to communicate with other humans. On one level this can be challenging when their map appears to be wrong, or broken. At which point we are left with two choices : either avoid talking to this crazy person entirely (or just talk about the weather), or enter into debate mode.

What’s happening of course is that we have all got slightly different maps. And if we don’t belong to the same tribe or culture, the maps can vary wildly, or be completely contradictory. Just imagine a Democrat debating a Republican, a Hindu debating a Muslim. Imagine debating a flat-Earther. It’s painful, it’s emotionally taxing.

Often the problem, when we are addressing someone with an opposing worldview, is that we are overwhelmed by our own psychological resistance. The goal of understanding our interlocutor is completely sidelined. Communication is lost. We find ourselves merely reacting to the emotional disturbances that arise when we feel that our view of reality is being challenged. My emotional attachment to what I know far outweighs any desire to learn, to listen.

Bias & Identity

Remember the bit about how I am also being represented on the GPS map? I am an integral part of a much bigger story.

There are many ways that the separate tales, the individual myths bind together to make a whole. Firstly our shared stories unite us as a culture, as a tribe. Furthermore, all the stories that I believe combine to create the tapestry that is my worldview. And finally, by participating in the world that I see, I too am connected.

Not only is my character part of the narrative, I often feel like the central character. By which I mean that the image I have of myself : my memories, my achievements, my goals etc.. is also part of my experience of reality. Our myths transform my tribe and I into actors in the cosmic dance! It gives us leverage. By performing the correct rituals together, singing the right songs at the right time, we can influence the seasons, make it rain, ward off eclipses, bring back the sun from the depths of winter…

Take a sports fan, which is a modern example of what I’m talking about. My identity as a Manchester United supporter will affect what I see out on the soccer pitch. The social dynamics that come with being who I am : a Red Devil, gives rise to some powerful cognitive biases. The other team’s fans, players, and even the referee at times, seem to be blind, evil, dishonest or living in some fantasy world.

We might be amazed by the antics of frantic sports fans, but our psychological resistance to opposing views often comes up in everyday life. I had a halting conversation the other day that consisted mainly of : “yes it’s true” and “no it’s not” repeated. And this was with someone who was part of my in-group : our local weekly meditation circle.

For some reason I had mentioned that there were some pretty horrible instructions in the Bible, which my friend immediately denied, saying “There are no rules in the Bible”. I think she misspoke in the heat of the moment, she probably meant to say : “The bible is not a book of rules (from an omnipotent God)”. Which I agree with wholeheartedly, it’s an attitude I share. I certainly don’t live my life as if it were. She was talking about her belief about the proper attitude we should take towards the book. I was referring to the words written on the pages of the book.

Unfortunately, the conversation, which included other friends, moved on, and we were unable to settle the argument. We were left hot and bothered whilst sipping our tea.

This kind of thing happens all the time. Despite my intellectual understanding of our experiential relationship to narrative, I still get caught up in my automatic emotional responses. My ability to describe some aspect of our evolutionary psychology, does not negate the millions of years of conditioning affecting my genes, my brain and my cultural environment. At best, it allows the possibility of recognising its effects, whenever they occur. It allows for a broader perspective.

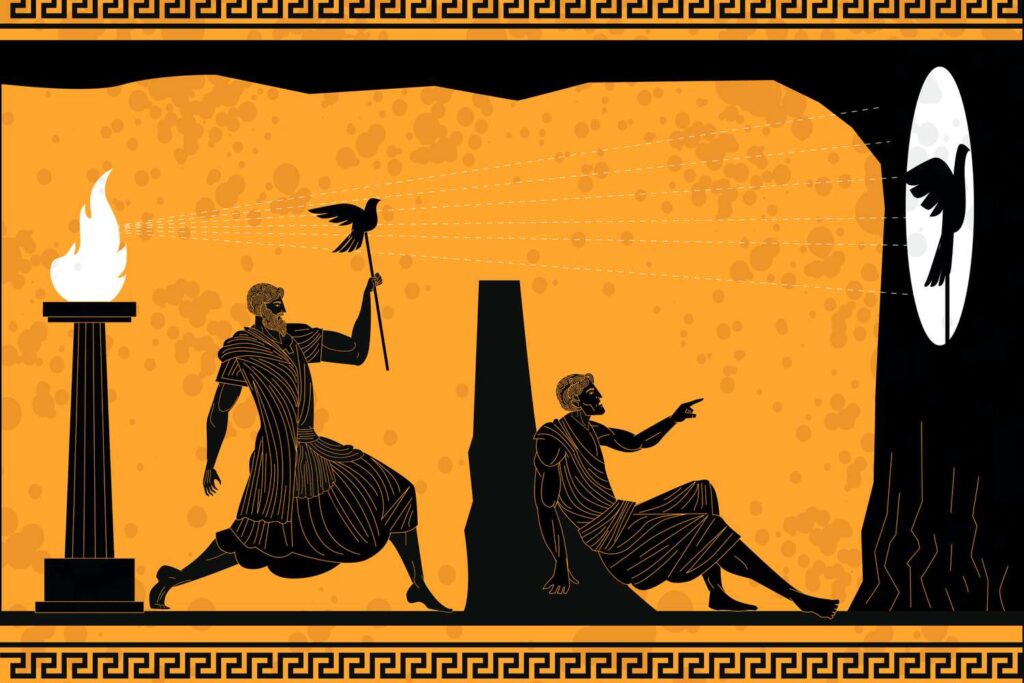

Shadows on the wall

If we consider Plato’s allegory of the cave, ie. The people reacting to the shadows of their own projections on the wall :

Allowing them a more complete picture of their predicament, changes their predicament. What they initially experienced as reality, is seen for what it is : a fragment masquerading as the whole.

Maybe this is a good time to quote Zizek : “The duty of philosophy is not to solve problems, but to redefine problems, to show how what we experience as a problem is a false problem”.

In other words, although we instinctively act as if our view of the world is fundamental, we are obviously ignoring the bigger picture . Our experience of reality is our ultimate authority, it’s the basis from which we react. Becoming smarter, for us humans, usually involves adopting better beliefs, more accurate models, which is laudable. But if we realize that we are conditioned psychologically, culturally to accept stories as truth, what happens then?

Can seeing the bigger picture, ie. that we are being mechanically driven by our experience of the world – just like any other animal, provide us with some wisdom, some respite? We are, allegedly, a very special animal : self-aware, able to apprehend complex concepts.

It’s tricky of course, very meta, because you are essentially being presented with another story. A weird self referential story.

The basic question implied by all this is simply : Is it possible to be free from our psychological imperatives when looking and listening? Can our relationship to conditioned beliefs be transformed? Or must we remain slaves to thought, always reacting emotionally, tied to our subjective, tribal narratives?

Is it possible to resolve cognitive dissonance, the emotional pain and confusion we feel when our identity and values are being threatened? Or is the feeling that our worldview is an exact reflection of actual reality too powerful?

We feel certain that our subjective experience has some sort of existence in our absence, that our model of reality exists somehow outside our brain. This is the principle of authority that drives us : what I know is reality, the stories I believe are true. By seeing this authoritarian principle at work within us, is its grip at all loosened?

There is nothing to indicate that this universe was designed specifically in order to be perceived accurately by its inhabitants. Nor is it obvious that any of our senses and brains were designed to detect fundamental truths. Maybe the idea that we could experience objective truth is not even a cogent concept. The quality of our understanding may only be measured by how well we can formulate it. Which in turn depends on our prior experience, stored in the brain as narrative. Is freedom from this narrative framework possible?

Whether or not some insight into the processes that drive us is possible, maybe it is possible to agree on the following : Relax. Our beliefs need not be weaponized. We should be kind to fools, like us, they have no choice in the matter.

No need to come to conclusions now. Next stop on this inquiry into who we are : Donald Hoffman, a cognitive psychologist with a great take on reality and perception.