“Stories are the way we make sense of the world, the way we find our place in it, the way we connect with each other.” – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, author.

This is pretty much the idea I would like to get across in the next few pages, here’s another great quote :

“The human mind is a storytelling organism. It craves stories the way the body craves food or water. It needs stories to survive.” – Jonathan Gottschall, literary scholar specializing in literature and evolution.

Our relationship with the tales we tell ourselves, the narratives we believe, is fundamental to how we view reality. What we call reality could in many ways be considered a story.

How we vote, the wars we wage, our fears, these are all intrinsically linked to stories. Even our idea of who we are, is essentially a story. By which I mean the memories of everything I have achieved, all my adventures, the image of the person I identify as.

The rise of the LLM’s

When ChatGPT was released to the world in 2022 many of us were astounded. IBM’s Watson had already won at Jeopardy (beating all the human champions), and Deepmind had beaten everyone at Chess and Go. So why were so many of the world’s intellectuals shaken by a Chatbot?

Obviously because this Chatbot had crossed a line.

The Turing Test is a story that has definitely become a part of modern culture, and this was Chat GPT’s major achievement : its ability to carry its part of a conversation like an intelligent human.

Pretty much immediately, over a 1000 signatories, mainly engineers, tech entrepreneurs and scientists, symbolically called for a pause in AI development to highlight what they saw as a potential catastrophe in the making.

Meanwhile, Yuval Noah Harari (Historian and author) made the rounds on podcasts and talk shows calling the event “the end of human history” – meaning that history, both the subject matter and the events that constitute it, would no longer be a purely human endeavor.

He also notably insisted on his rather quirky claim that AI was on the verge of “hacking into Humanity’s Operating System” (OS).

The advent of Large Language Models (LLM chatbots) was essentially a wake up call to address the worrying state facing our civilization. A problematic situation that we have been knee deep in for a while now : Post truth.

How does technology hack into our OS?

It’s complicated, but to quote Mr Harare : “our brains are constantly producing stories, stories which come between us and the world”.

The implication being that our biases condition our worldview, and our worldviews inform our actions.

Now if the Algorithms that track and exploit our biases (on Facebook or Google for example) can be combined with the storytelling capabilities of LLM bots, to confirm and direct those biases, this could be catastrophic for a primitive society dependent on narrative (like ours).

Just to balance out this rather worrying hypothesis, the argument has been made, notably by Mr Bot in the Economist (August 2023 article), that we might be undergoing a sort of Fake news burnout. Meaning that the constant barrage of misinformation has rendered us increasingly immune to novel ideas of any kind, whatever the source (AI or human).

By living under a continuous avalanche of misinformation we have been inoculated against it. Unfortunately this inoculation has further reinforced our initial biases – we seem to be even more polarized along tribal/political boundaries.

That’s a quick snapshot of our current imbroglio with information. Now let’s keep that in mind as we look at some scholarly research into our enduring fascination with fables.

Polyphemus the Cyclops

The following is a summary of Dr. Julien d’Huy’s book “Cosmogonies”, in which he traces a genealogical tree around the ancient Greek story of Polyphemus, the cyclops.

Julien d’Huy is a history professor, and his book addresses the question of why similar stories exist all over the world in completely different cultures.

Carl Jung famously formulated a popular claim about this question with his idea of a “collective unconscious”. The idea being that the same legends appear in distinct, distant civilisations due to the fact that all humans share common experiences and emotions.

This is not the case presented in Cosmogonies – the thesis is flipped, in that our shared mental archetypes find their source in the stories that we have been telling each other since the dawn of language and culture. Since we first sat around the campfire, peering into the darkness, trying to find some sense in what we saw.

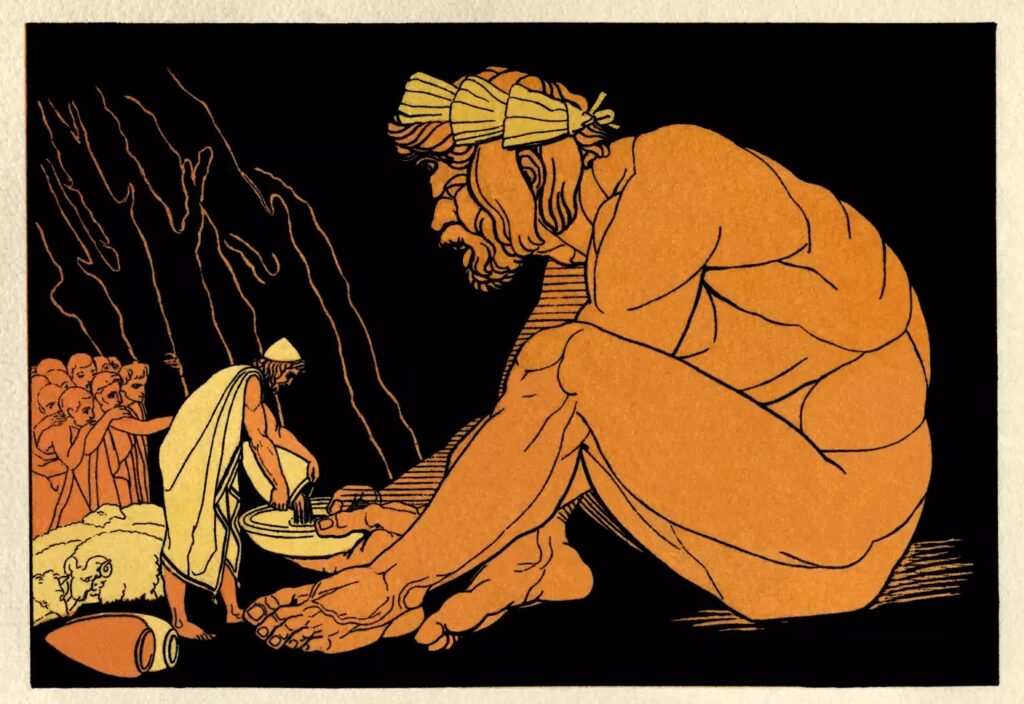

Dr. d’Huy presents his case by constructing charts that highlight the relationships and similarities between groups of myths from all over the world with common themes and characters. Very much like a Genealogist would construct a family tree. The idea being that if myths evolve, like biological organisms, we can draw a family tree where each story is slightly different but related to its predecessor.

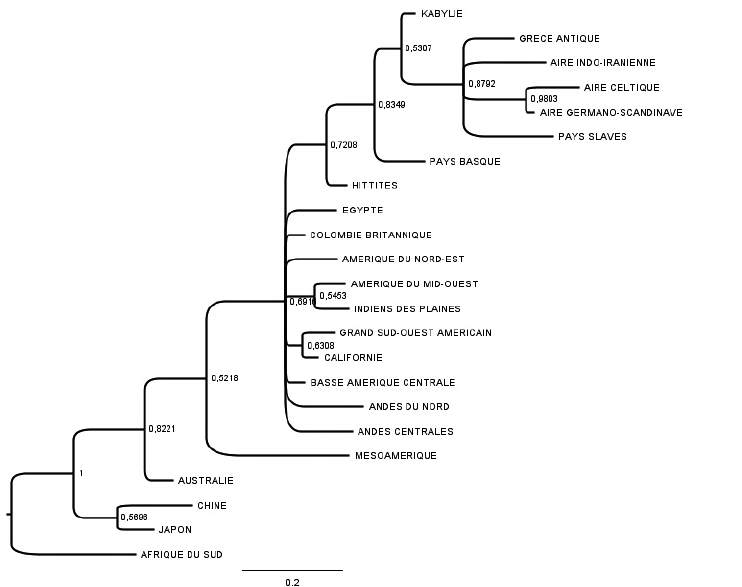

He then compares the chart with what we know about early human migrations out of Africa and their subsequent spread around the globe. Knowledge derived essentially from archeology, genetics and the history of languages.

And if the data matches up, Voila! Evidence that we carried these stories with us to our new homes – whilst simultaneously thwarting any assumptions that the sharing of these stories might be a modern phenomenon (eg. due to colonization or globalization) or due to some ancient worldwide revelation. If the chronological evolution, ancestry and spread of these myths happened in sync with early human migrations, then they obviously neither appeared at a later date nor all at once.

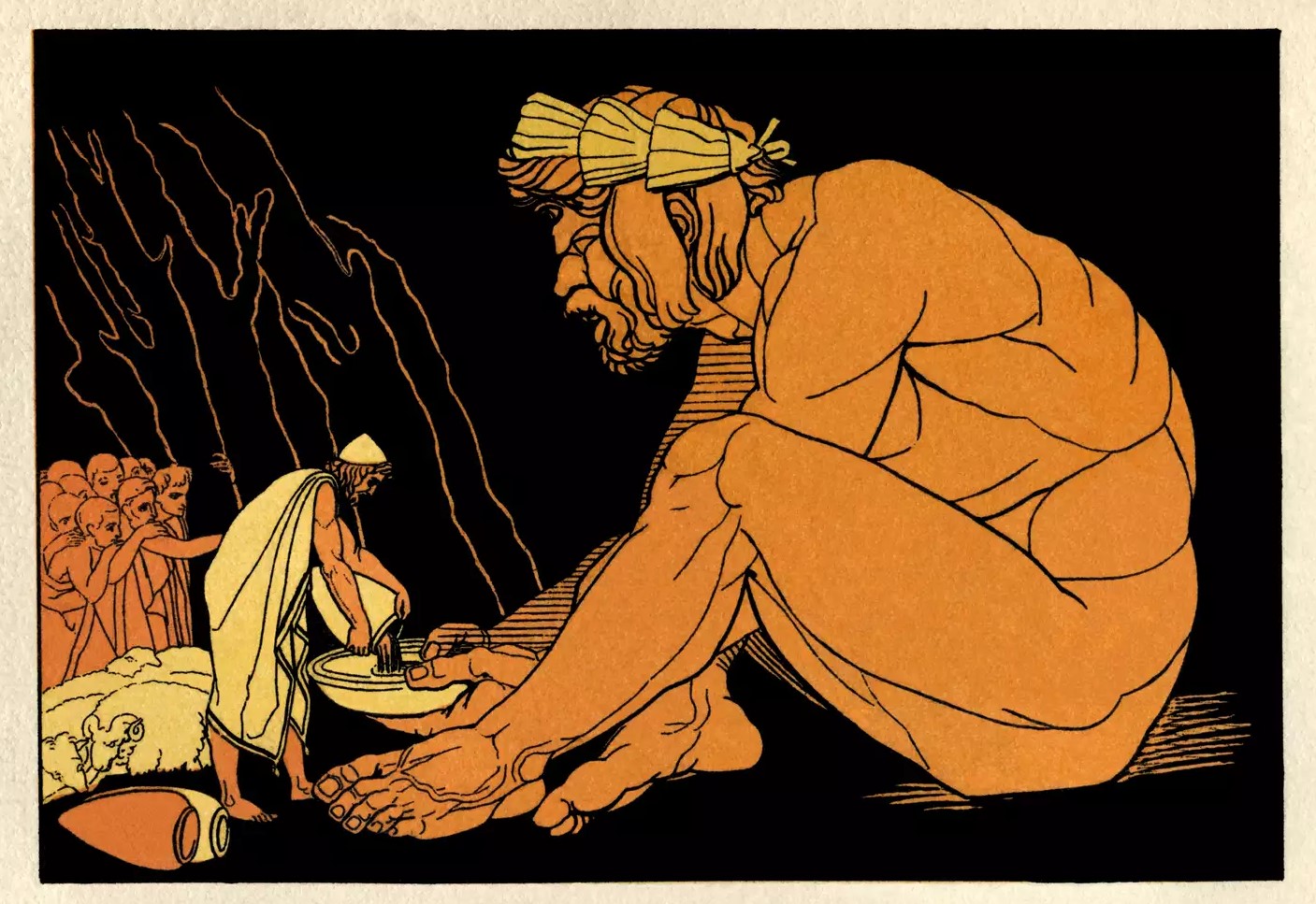

So, anyway… Polyphemus was a Cyclops (a one-eyed, man-eating giant) who lived on the island of Sicily. He was a brutish demi-god, whose power over nature yielded a bountiful supply of food at will.

One day, the hero Ulysses, on his way back from the Trojan wars, comes ashore looking for food. Which, it turns out, was a bad move. He manages to get trapped by Polyphemus in the cyclops’ home, a cave which he happens to share with a flock of sheep.

Fearing for his life, and accustomed as he was with various feats of derring do, Ulysses fashions a rudimentary spear, which he then uses to blind his foe, and finally makes good his escape by hiding under the aforementioned sheep as they are let out to pasture. The end.

This is a familiar story to many of us, mainly because it was written down when the ancient Greek civilization was flourishing, most famously by Homer (nearly 3000 years ago). But folktales, very similar to this Cyclops story, have been told all over the ancient world. More than 200 different versions have been identified, from around 25 countries ranging from Iceland to Africa, and from Turkey or Ireland to Korea.

The scholarly consensus is that many of these Polyphemus type legends predate Homer.

For comparison, here’s the summary of a similar story from North America :

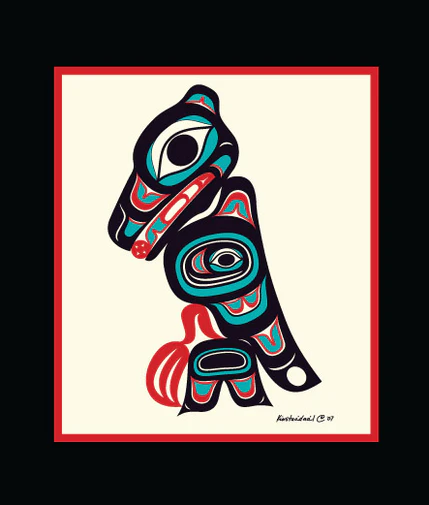

Raven (a man/bird hybrid trickster entity) hides some buffalo in a cave. He is forced to reveal their whereabouts but refuses to set the buffalo loose. Two local heroes manage to get into the cave and create a stampede. And they get past Crow, who is guarding the entrance, by hiding under a buffalo skin as the herd charges out to freedom.

Unraveling the mythological roots

The central theme of the story is as follows : a hero visits a dangerous creature, a sort of primitive ruler of animals, and has to escape with the help of those animals, or by disguising himself with their fur.

If we collect all these stories from around the world and compare them, we can further organize them based on the frequency of any other narrative details they may share. For example, the names, descriptions, motivations, attitudes or number of protagonists involved. Or the tools and/or methods they use, or the geographical features mentioned etc..

By comparing the similarities between the versions we can figure out how they are related to each other in space and time. These relationships are confirmed somewhat if they mirror the historical data about human migrations and conquest. For example, 2 very similar stories from Iran and Mongolia could be explained by the fact that the Timurid empire, which was basically a dynasty with direct Mongolian origins, ruled over Persia (aka modern day Iran) for over a century.

The family tree that Dr. d’Huy manages to build around the cyclops story mirrors humanity’s initial migration out of Africa. His findings are very much in line with previous research on the subject (by Andrey Korotayev and Darla Khaltourina in 2011).

Korotayev et al. states that the Cyclops story is related to an ancient myth about how all wild animals were originally kept in one place before being liberated and dispersed around the world. They also insist on the correlation between the spread of these myths and human migrations in the late paleolithic; specifically that the stories were disseminated along the same lines that our mitochondrial DNA dispersed from central Asia. Places near the point of origin (eg. southern Europe & central Asia) thus sharing more narrative details than those further afield (eg. America).

Information being subject to change, and civilisations subject to collapse, some versions of the myth have vanished completely, and in some places only a kernel, alluding to a king of all the wild animals, survives. As most of what we are dealing with here happened in pre-literary societies, it’s amazing that any of these tales are still around today.

Let’s now take a quick look at how these oral traditions succeeded at all in passing these stories along to us, from 60 thousand years ago. Hopefully we can look at a couple of other versions of the story, and finally circle back to what effects these stories might still be having in our modern beliefs and behaviors.