Perception vs. Reality

Donald Hoffman’s theory goes roughly like this :

Our senses help keep us alive. They help us avoid tigers and snakes, or getting run over by buses. They make us gag and heave at the smell of rotting food, they make chocolate taste delicious. That’s what our eyes and ears are for, it’s their whole purpose.

Our senses allow us to discriminate between this and that, in order to react if need be.

And these abilities : to distinguish between red and green, between a hiss and a grunt, were honed by Evolution. Our ancestors : the creatures who acquired these particular skills, survived. They survived and passed on their genes.

Thank you very much. Thanks to my ancestry, I see the world in a way that improves my likelihood of survival – or at least in a way that has been useful so far (Oups! Sorry, I added that last remark – not sure it’s actually in the book).

Now, we assume that our senses are telling the truth, that they are providing us with an accurate image of reality (note from me again : the folks that didn’t assume as much probably went extinct). In fact, we very much expect that the more accurate an image is, the more useful it will be. As in : information that is correct increases my chances of staying alive, and incorrect information will get me into trouble. Sounds like simple common sense.

Hold on a second there! (says Hoffman) Unsubstantiated claim! Where’s the argument leading to your conclusion?

Just because I avoided getting run over by the bus, doesn’t mean the bus is actually as I perceive it to be. Just because what I see helps me stay alive, does not guarantee I am not being deluded.

In life and death situations, it’s what I do that counts, not what I think is making me do it. The scarier the thing appears to me, the faster I will run. Subtleties like truth or accurate perception are secondary.

For starters, hopefully we can all agree that we don’t really see a complete picture of the world. Some things are just too small, or they’re too far away, or they’re in the wrong wavelength – we can’t see them.

Also, if we were paying attention in Biology class, we know that our eyes and ears do not provide a direct window onto the outside world.

For those of us who were being befuddled by puberty at the time, here’s a quick reminder : Our sense organs provide the brain with electrical signals. Our brain then interprets those signals in order to create a visual, auditory and emotional experience. Our conscious experience (what we call reality) is a projection happening in our minds.

Fitness Beats Truth

So the hypothesis we have to defend here is that our brain is trying to get us to make babies, it’s not trying to reveal fundamental truth. Let’s call this hypothesis : Fitness Beats Truth (or FBT).

FBT states that our senses have evolved in order to give us what we need, it’s not concerned with painting a true likeness. It even states that a complete or complex picture of reality would actually be a handicap. Experience is about usefulness not truth.

Straight off the bat our hypothesis wins 10 points, because it aligns nicely with the theory of Evolution and Natural Selection. At least the bit about how our physiological characteristics, like our eyes and brain, are selected for based on how well they help us survive.

Being in line with established theories like Evolution is fine and dandy. But providing evidence for your own claims is even better – it doubles your points.

Hoffman does this by getting his students to run survival games on a computer, using principles from Universal Darwinism and Game Theory.

Universal Darwinism describes the mechanisms affecting evolution, like genetic diversity, natural selection and heredity. It’s universal in the sense that these mechanisms can be used to explain any phenomenon that evolves. Not just biological species, but also how societies end up in particular configurations. Or why human psychology or languages or economic systems appear the way they do.

Game theory is the study of strategic interactions between agents – like when people play chess against each other. It determines outcomes based on the strategies used (usually in competitive – but sometimes cooperative situations) – like a simple chess bot would.

By programming a game with these principles we can see what works best : accuracy or fitness. In other words : we use evolutionary game theory to run a computer simulation, and we look at what kind of creatures survive.

And the answer is always : those that perceive utility.

To be clear, we create an artificial world, on a computer, in which entities with random abilities are let loose. These abilities are things like : what they are able to perceive, how they move, what they can eat. The digital creatures that manage to survive the best are kept and bred for the next generation.

What we find is that the perception of the creatures that survive increasingly evolves towards identifying what is useful. In some rare cases accurate perception persists, but only if strongly correlated with fitness.

Pattern recognition monkeys

Of course, some of us might not be happy with this so-called evidence. Proof by computer games? Nonsense! That’s not a thing – it’s just math, logic and a bunch of 0’s and 1’s in a machine – you don’t get 10 points for that! What about some real life evidence?

Well, we could look at a common trait shared by many animals (including us) : Risk aversion. Risk aversion simply means that we have a strong tendency to avoid really dangerous situations; that we prefer less risky situations whenever possible. It’s a tendency even relatively primitive animals have, so it’s been around a long time. And the fact that it’s also one of the most widely observed behaviors in the animal kingdom, leads us to suspect that it must confer a certain evolutionary advantage.

The point that interests us is that our tendency to perceive and avoid danger may help keep us alive, but that it isn’t accurate. Or that accuracy is besides the point. Or that any desire for accuracy can in fact have negative consequences.

Consider this popular explanation of how we humans came to be pattern seeking animals. “Pattern seeking” in this case, refers to our bias towards assigning meaning, agency or connections without good reason.

The story starts way back when our ancestors were wandering around the savanna in search of subsistence. We were meek and mild mannered folk back then. These were the good ole days when we recognised our proper place on the food chain (ie. somewhere near delicious suckling pigs). No AK47s nor bows and arrows were available. In those days when we noticed some rustling in the bushes nearby, we would scarper.

That’s because we are the descendants of other scarpering animals. Tiny delicious mammals that do not scarper, maybe because they want to know for sure what’s moving in the bushes, don’t make babies, don’t have descendants. They get eaten. Maybe they don’t get eaten straight away, and maybe they can take pride in their more accurate view of the world. But they don’t survive as long as their friends who think that saber-toothed monsters are hiding behind every bush. Our ancestors may have been wrong 99% of the time, but they survived to be wrong another day.

Fitness dictates that it’s better to flee unnecessarily from a potential threat that isn’t actually there, than to hang about and check whether we’re mistaken.

Action or accuracy?

Moving swiftly along, here’s a little thought experiment that might give further credence to the FBT idea :

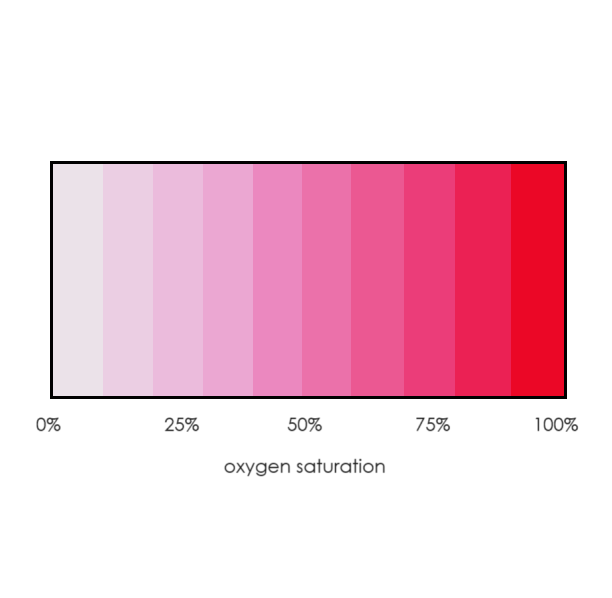

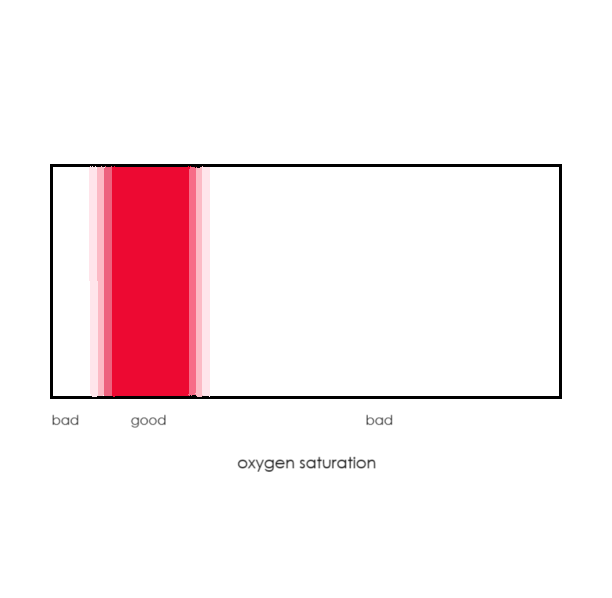

Imagine that we were creatures living on a small planet on the outskirts of Betelgeuse. Furthermore, imagine that we needed the air we breathed to contain around 20% oxygen. Too much oxygen and we would die, too little and ditto. Now, let’s say that the oxygen levels on our planet vary, making some places dangerous to hang out in and others just fine.

Anyway, many creatures living on this planet have evolved the ability to see the air around them. Because, as we know, evolution by natural selection favors traits that help us survive. Being able to perceive the quality of the air around us helped keep our ancestors alive. Is this alien story making sense so far?

If so, we may consider this question : which of the following abilities would be better, being able to accurately perceive the quality of the air, or just being able to discriminate between good air and bad air?

To help us decide, here’s what these two different ways of seeing the air might look like :

Hopefully we can agree, at least in this case, that a more accurate perception of reality doesn’t really improve our chances of survival. We might even agree that the subtleties that come with increased accuracy, would also require more time and energy to process. Time and energy that could be better spent scarpering to safety.

Nature is full of simple organisms that survive without any representation of reality whatsoever. Reaction to stimuli, without the need for any conscious conceptual experience, has been the norm for most of this planet’s biological history. Big brains were latecomers to the scene. And as we know brains are what provide us with our conscious experience of what’s what.

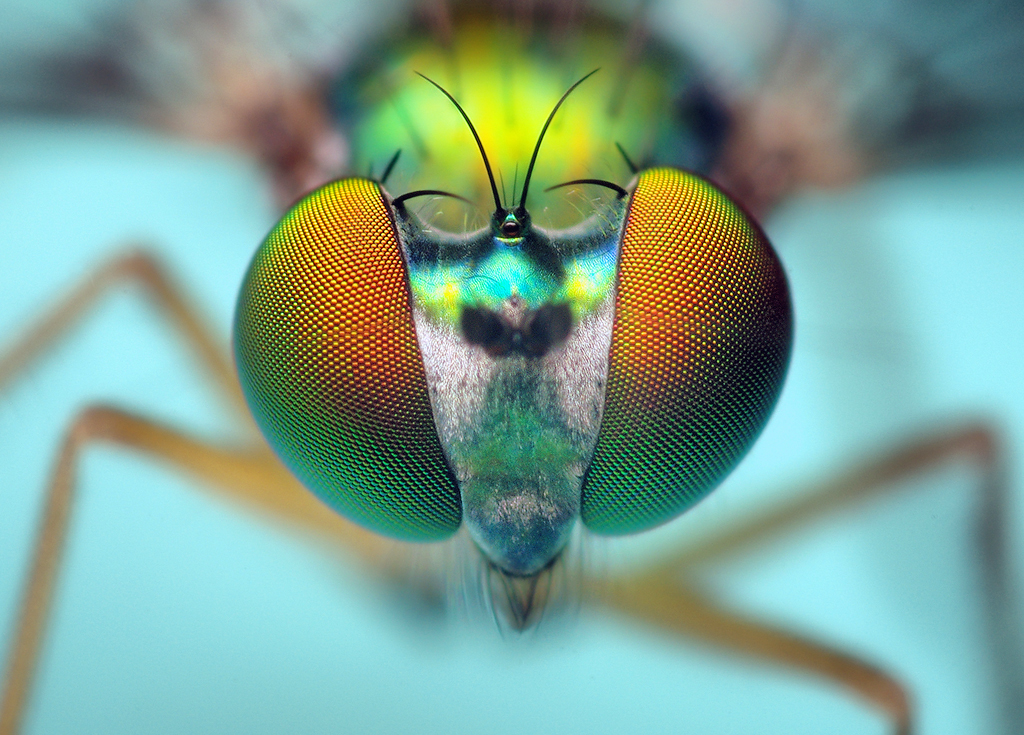

Take the common Housefly, as anyone who’s tried to swat one knows: it’s really good at surviving. And this despite having practically no brain. Which means that it probably doesn’t have much of an idea of what it’s perceiving at all. As far as we can tell it’s just reacting to movement – thanks to signals from its amazing compound eyes. Houseflies have been around for much longer than us, without ever needing to know about what exactly was going on.

Someone could reasonably argue that our perceptions aren’t really incorrect, just lacking in complexity. For instance, in the case of our space aliens living near Betelgeuse, who only perceive differences between good air and bad. The air that they perceive as good really is good, the bad air really is bad. The fact that a simplistic experience of reality might be more efficient, doesn’t mean it’s false.

The mistake being made here is what’s called a category error. We are equating preference with truth.

It may be a fact that I think poop is disgusting. But that’s just a fact about my subjective opinion, not a fundamental truth about poop. As you know, dung beetles hold poop in high esteem.

Maybe this is all a bit hard to swallow, and we are racing through Hoffman’s arguments here. But our brains do really seem to be geared more towards problem solving, rather than towards an accurate depiction of reality. Just because I believe a story is true, doesn’t make it so. Just because one of the solutions we come up with actually works and gets us what we want, does not mean we understand what’s really going on.

Take a look at this :

The brown rectangle on the left side of the hat is the same color as the yellow one on the front (or the right) of the hat. It’s hard to believe but our brain is playing tricks on itself in order to get by.

Try putting on a pair of rose colored glasses – the world might look rosier for a while, but your brain will eventually adapt. In due course, despite still wearing those glasses, the colors you see will start to appear quite normal again. Your brain wants you to be able to function properly, and it’s willing to lie in order for you to do so.

Interface Theory of Perception

Anyway, let’s tie a bow on this chapter with what Hoffman calls the Interface Theory of Perception (aka ITP). Hold on to your hats, here’s the theory in a couple of paragraphs:

Microsoft Windows OS is the interface I use to navigate around my computer. The reality I perceive are the icons on my desktop: the folder and the trash bin for example. These icons are useful representations that allow me to do my work, but they are illusions; in no way do they resemble what is actually happening in my computer. What’s actually happening in my computer is hidden to me, but there’s nothing in there that resembles a file or a trash bin icon in any way. We usually try to describe the mysterious processes going on there as an algorithmic manipulation of information in the form of 1’s and 0’s. Or as a series of information gates on electronic circuit boards (or whatever, I don’t really know what I’m talking about, sorry). The point is, even though I must take what I see seriously, it’s an illusion. I will take care not to drop my files into the trash bin if I don’t want to lose my work – even if they’re merely symbolic representations of what’s actually taking place.

Now ITP postulates that Spacetime is the interface I use to navigate around the universe. The reality I perceive are the objects in spacetime that I experience. These are like the icons on my computer desktop – they allow me to manipulate a more fundamental, unseen reality. We must take them seriously, especially buses, trains and rattlesnakes, because we will really die, or be late for work. But they are just useful experiential representations of some more fundamental reality.

Hoffman is quick to point out that he’s not the first to make the crazy claim that Spacetime itself might not be fundamentally real. The non-locality inherent in quantum mechanics for example, causes some physicists to make the same allegations.

ITP also conveniently counters any suggestions that our shared vision of reality might constitute an argument for objective truth. If we can all agree on the facts then they are surely facts, not just subjective beliefs.

Unfortunately, our use of the same interface would also explain why we all see the same icons.

So, if I’ve managed to keep score correctly, that’s probably 30 points to Hoffman and 0 for reality.