Are we getting smarter?

Let’s start with a couple of questions. Now that we’ve acquired the tools of logic and reason, now that we’re so smart that we can build rockets, it seems only natural to assume that we are smarter than more primitive folk. I mean : are we more intelligent than a hunter gatherer? Or if that seems too tricky to answer : are humans smarter than chimpanzees?

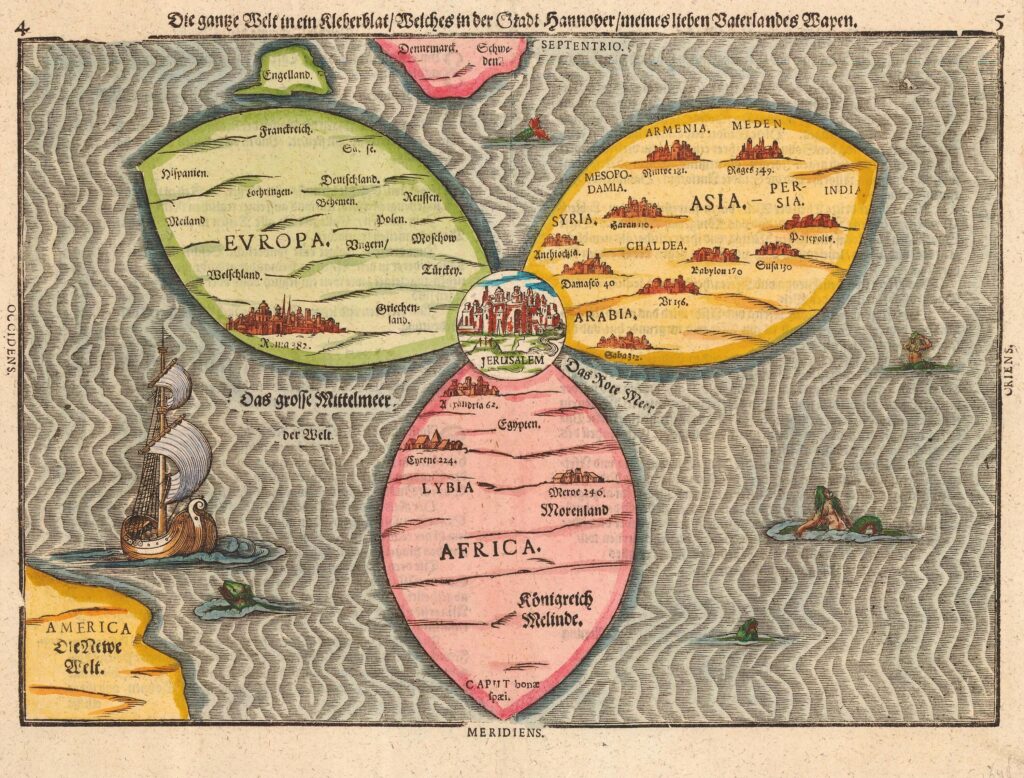

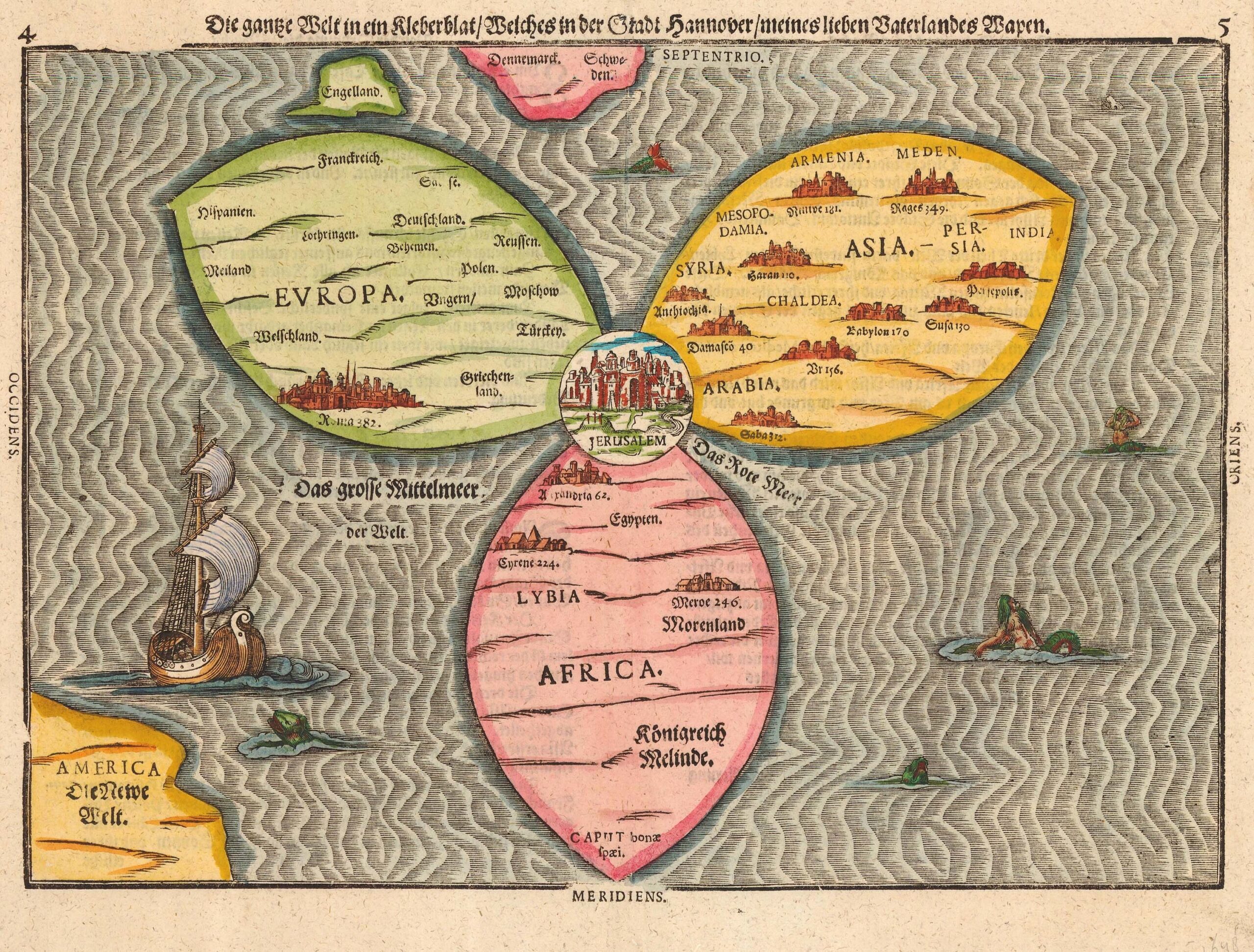

I realize that this is an emotionally charged question. It’s not a competition as in : who’s better? Chimpanzees are obviously better at climbing trees, more muscular than us, and of course more handsome. Rather I’m asking about our understanding of the world. I have been to school, have learnt to speak 2 languages, can now easily count to over 100, add and subtract, have notions of geography, philosophy etc.. So does my vision of the world align more accurately with reality than theirs? Do all the things we know really grant us a clearer lens through which to relate to the complexities of our life?

Man vs wild

We do have data relating to these questions. One interesting phenomenon, when comparing the intelligence of a modern educated person against someone from a traditional cultural environment, are reports about failed expeditionary campaigns. By which I mean groups that have been deliberately put together with the express purpose of exploring some strange foreign land. Top notch individuals, perfectly suited to the task at hand, are chosen, by some well funded military or scientific organization, and end up having to be rescued by primitive savages.

We are talking about educated white men, usually scientists and military personnel, vs. Aborigines, Inuit or Native Americans. The test being : who has the best chance of survival in a hostile environment (no shopping centers, no restaurants, no Ubers).

Alas, the story I think is a familiar one : the group of intrepid explorers, faced with a hellish desert of ice, sand or overly lush forest, mainly end up dead.

This despite the fact that they do so in what the locals deem to be their backyard, a lovely place that provides them with all the food, medicine and material they need.

One example is the Burke & Wills expedition of 1860. Lots of dead white guys there. Burke and Wills both dying despite being shown by locals how to find and prepare an abundant native source of food : nardoo, a variety of clover.

Unbeknownst to our intrepid explorers, nardoo is toxic, and consuming it without first leaching out the toxins can be fatal. The interesting thing is, the natives probably did not know how dangerous this plant was either, they just knew the “proper” way to cook it.

It’s actually very difficult to figure out that nardoo is bad for you. Eating nardoo does not make you feel sick at all. However it does contain an enzyme that breaks down Thiamin (ie. Vitamin B1), an essential nutrient. So, if you’re consuming large quantities of that enzyme, and not eating anything that might provide you with any Thiamin, like meat or fish, death ensues, eventually.

You might be wondering whether it’s fair to claim that even the natives themselves didn’t know why they only ate nardoo that had been prepared in the proper way. Thing is, you can just ask them. They don’t know. The question itself is considered weird. Why would we need “reasons” to do the right thing (ie. our proper, traditional, way)? If some strange tourist asks me why, I might realize that they want me to provide a reason, so I might try and make one up, but that’s about as far as it goes.

We aren’t describing some rare mystery specific to nardoo and Australian aborigines either. This kind of thing happens all the time, all societies are blessed with really clever life enhancing techniques and taboos. Techniques and taboos whose origin is difficult to explain.

Like for example, the Mapuche people in Chile who traditionally add ash to corn before cooking – an addition that allows the corn to release Niacin (an essential nutrient). Or taboos in Pacific island cultures that forbid pregnant women from eating popular everyday foods that we know now (thanks to our knowledge of chemistry etc) could harm the fetus.

How did people manage to come up with such beneficial strategies if they had no way of knowing that the strategies could even be beneficial in the first place? Why does the society perpetuate these strategies despite there often being no obvious reason to do so?

It used to be that we could explain these mysteries with a story about some ancestor interacting with the local gods. The theory these days is that it’s all to do with our relationship to culture. Simply put :

- Everything that happens in the culture we are born into, is instinctively taken to be a normal, fundamental truth. For example, I feel just as strongly about gravity as I do about eating dogs : heavy things always fall to the ground when I drop them & dogs are not food (according to my Euro-centric upbringing)

- Cultural groups are affected by the same rules of natural selection as biological species. The traditions that exist within the most successful tribes will spread, and these traditions will tend to be either neutral (have no effect whatsoever) or beneficial to the survival of the group as a whole.

Over time, these 2 simple rules can allow complex systems to become part of a tribal tradition without anyone consciously planning anything. A misunderstanding here, a lucky intuition or mistake there, that is copied by successive generations, and voila : without actually getting smarter, a tribe can nonetheless build up a huge library of potentially useful habits and tools.

Roald Amundsen, the first man to reach the North and South poles, famously capitalized on this bonanza of traditional knowhow. Despite the advances of science and industry, no one in the modern world at the time (ie. early 1900’s) was able to produce anything like the quality of equipment used by the “primitive” Inuit culture. Much of Amundsen’s success owes a huge debt to his having lived and learned with the Inuit, and the use of their dog sleds, hunting equipment and clothes.

Anyway, in contrast to the stories of white men dying in the wild, we could also mention stories of tribal women being abandoned and left to fend for themselves alone. How do they fare? Much better apparently.

Consider the Pacific islander, christened Juana Maria, abandoned somehow by her entire tribe in 1835 when they all decided to move to the mainland. She survived quite happily for nearly 20 years, and when finally “rescued” as an elderly lady, was able to offer presents and refreshments to her rescuers.

1-0 to the primitive savage?

Not necessarily. The examples above aren’t really fair. People in a familiar environment aren’t usually going to have trouble getting on with their lives, and anyone in an alien environment is just going to feel at a loss. But still, it does make it difficult to claim that a modern, educated human is smarter than someone with a traditional, tribal upbringing.

A group of intrepid polar explorers whose ship gets stuck in the Arctic ice over winter, even if the ship is crewed by scientists and engineers, is probably not going to be able to invent any useful survival techniques. Like for example, ways to keep warm, acquire food, make tools or clothing.

Their survival will depend entirely on how well their ship holds together and the amount of provisions they managed to stock up on.

However, nearly everyone belonging to the local indigenous culture will have learnt a whole load of amazing and useful tricks and tactics, simply by observing and imitating their peers. Could we say that intelligence is more a product of the culture than the people within it?

This would explain why we might think that modern humans are more intelligent than an uneducated person living in some jungle tribe : we are confusing the technology available to someone with their brain power. The scientific method, the industrial revolution, and capitalism, means that everyone in the modern world has access to really space age tech and toys.

But it would be a mistake to assume that the more tech my culture gives me access to, the smarter I am.

A definition

Intelligence is typically defined as : the capacity to acquire and apply skills and knowledge. Which, in the examples we have been looking at, could be translated as : the ability to respond adequately to a given situation. So, when placed in an unusual or alien environment, modern humans seem to do no better than their traditional counterparts.

In fact, for humans what we call intelligence seems to be a measure of how well we manage to integrate cultural customs. Human intelligence is intimately tied to culture and context. If I display a good knowledge of proper social etiquette, express myself eloquently in the local patois, share the same worldview as you, and manipulate my smartphone with ease, this would probably be proof enough of intellectual competence. At least for someone in Singapore, San Francisco or Stockholm. In a more traditional culture you would have to swap smartphone for the appropriate technology, like canoe or boomerang.

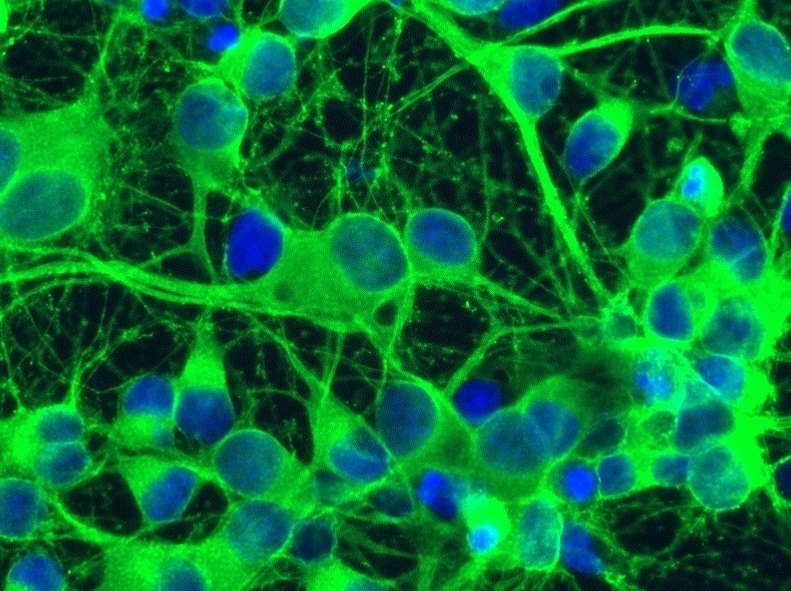

This does not mean that our brains are not changed by our cultural conditioning. A young mind that is brought up on a daily regime of data accumulation and comprehension, and accustomed to solving mental puzzles (ie. goes to school) is likely to have a higher IQ. A brain that learns to read is going to be wired noticeably different from one that doesn’t. A mathematician gonna be good at math, philosophers gonna “philosophate”.

The point is that specialization is not synonymous with improvement. The point is that the next development in any field of knowledge is dependent on a library of existing knowledge. We are standing on the shoulders of a huge pyramid of normal sized people. And nothing indicates that we are any more creative, clairvoyant or insightful than they were.

Okay, what about the man vs. chimp question we asked at the beginning of this chapter? Maybe if we look into the data about that we might gain some more insight into the idea of intelligence as a cultural phenomenon?

2 responses to “Intelligence is cultural”

-

Josy

Douglas j’ai eu beaucoup de plaisir à te lire.

C’est très instructif et intéressant.

J’avais pleins d’images qui apparaissaient au fur et à mesure que je lisais.

J’ai trouvé ta façon de décrire et d’expliquer très accessible.

Moi qui ne suis pas du tout scientifique et d’une intelligence dite “normale”.

Pour moi la vraie intelligence est essentiellement celle du coeur.-

macdougdoug

Merci Josy, c’est gentil. Perso la traduction française du texte m’embête un peu – je vais voir si chatGPT peu me proposer quelque chose de plus facile a lire.

-

Leave a Reply