The Planet of the Apes

In Pierre Boulle’s novel “The Planet of the Apes”, we are presented with two main themes : that humanity’s reliance on technology is the cause of their downfall, and that the rise of the monkeys is due to their capacity for imitation.

Mr. Boulle wrote his novel in 1963, and since then the worrying idea that technology is somehow making us weaker and dumber is still part of our collective consciousness.

We are pretty wimpy. Whilst monkeys are treating their environment like some kind of muscle gym, we are staring down at our phones and letting robots do all the hard work. No one wants to fight a chimp. And if me and some ape were dropped naked into the jungle to see who would survive, I don’t think anyone’s betting on me.

Natural selection is all about the survival of the fittest. So the idea goes like this : the fact that technology now takes care of all the heavy lifting – whether mental or physical – means that our muscles and brains are degenerating through lack of use. And thanks to medical science we may even be creating a population of humans that wouldn’t normally be able to survive and reproduce – thus, in a way sidestepping natural selection.

The worry being of course that when the zombie apocalypse (ie. when civilisational collapse) finally happens we would be doomed to extinction, unable to function without our smartphones, hospitals or vending machines.

Intuitively, it does seem like we are actually less well equipped to survive in a hostile environment than our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Have we been evolving backwards? Is our ability to sidestep natural selection creating a species of degenerates?

Let’s consider another animal like the Cheetah for example. Say we noticed that the successive generations of Cheetahs breeding in zoos were becoming less and less able to run as fast as their wild counterparts. That the world’s fastest sprinter was losing its evolutionary edge. We might worry about their chances of survival if all the zoos closed and they had to fend for themselves in the wild.

Is this hypothetical Cheetah scenario the same as ours? Are we losing our evolutionary advantage? What exactly is our evolutionary advantage? If the Cheetahs speciality superpower is speed, what’s ours?

Skills where humans seem to outdo other animals are manual dexterity, imagination and language. So maybe we don’t have to worry about technology making us less muscular than our ancestors. Anyway, how far back do you want to go?

Early humans were pretty much always using tools. Just the adoption of spears and cooking already changed our guts and muscles from the get go. I don’t suppose anyone is saying that we never should have started using spears (or rocks) or cooking our food.

Muhammad Ali and Arnold Schwarzenegger are fine muscly specimens that have contributed much to the human endeavor, but so has Stephen Hawking.

The fact that Stephen Hawking was able to live to the age of 76, despite not being able to speak or move for much of his life, has a lot to do with the fact that we are social animals.

Like Elephants and Meerkats, helping, sharing and cooperating is part of our instinctive behavior. In our case to the degree where we try to enlarge the net of care to our whole species. When we can, we leave no one behind.

The fact that Stephen Hawking was able to contribute so much to society is pretty amazing. It’s partly thanks to technology of course, and is very much linked to something that is uniquely special about humans. Joseph Henrich (yes the same guy that came up with the WEIRD theory of mind) reckons that we might be the first cultural species. Let’s look at what this means.

The art of imitation

Since we promised to pit man against ape, let’s start there.

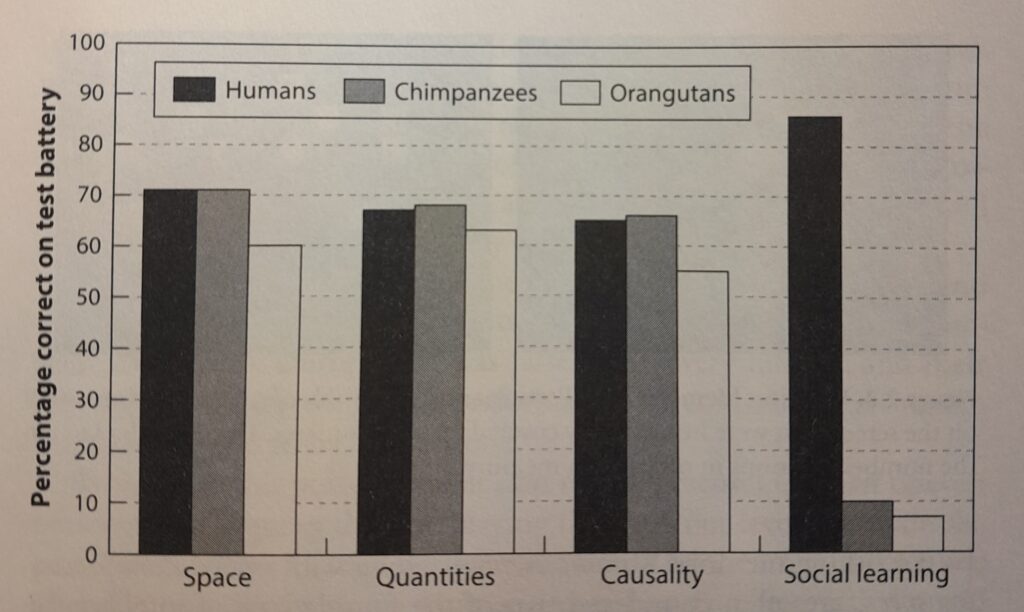

In 2007, Dr Esther Herrmann (PhD Evolutionary Anthropology) & friends published a paper where they described the following experiment :

Dr. Herrmann (& friends) managed to gather together a group of toddlers (between 2 and 3 years old) and pit them in a battle of intelligence against a horde of chimpanzees and orangutans. Our antagonists were presented with 38 challenges, which were supposed to test 4 different types of intelligence.

- Spatial Awareness. For example, are you able to build a 3D model from a 2D picture using some building blocks?

- Math. Can you assess relative quantities? Can you add and subtract?

- Causality. Can you choose the best tool for a particular job?

- Social Learning. Can you solve a seemingly impossible puzzle if some expert does so in front of you?

And the results are as follows

Firstly we should say that no Orangutans were mocked for their scores in these tests. Also they do have the best fur coats, lovely red hair. And surprisingly the only thing where humans came out tops, and by far, was in imitation.

In the words of Dr. Herrmann : “contradicting the hypothesis that humans simply have more “general intelligence,” we found that the children and chimpanzees had very similar cognitive skills for dealing with the physical world but that the children had more sophisticated cognitive skills than either of the ape species for dealing with the social world”.

If you’re wondering whether it was a fair comparison, seeing that our species was being represented by infants, just remember : we were trying to keep to a level playing field with regards to acquired knowledge.

The idea being that what is considered superior intelligence in humans may just be a form of accumulation. Also the age of monkeys doesn’t really matter, seeing as they don’t get much smarter as they get older.

In any case, we have more :

The amazing Ayumu

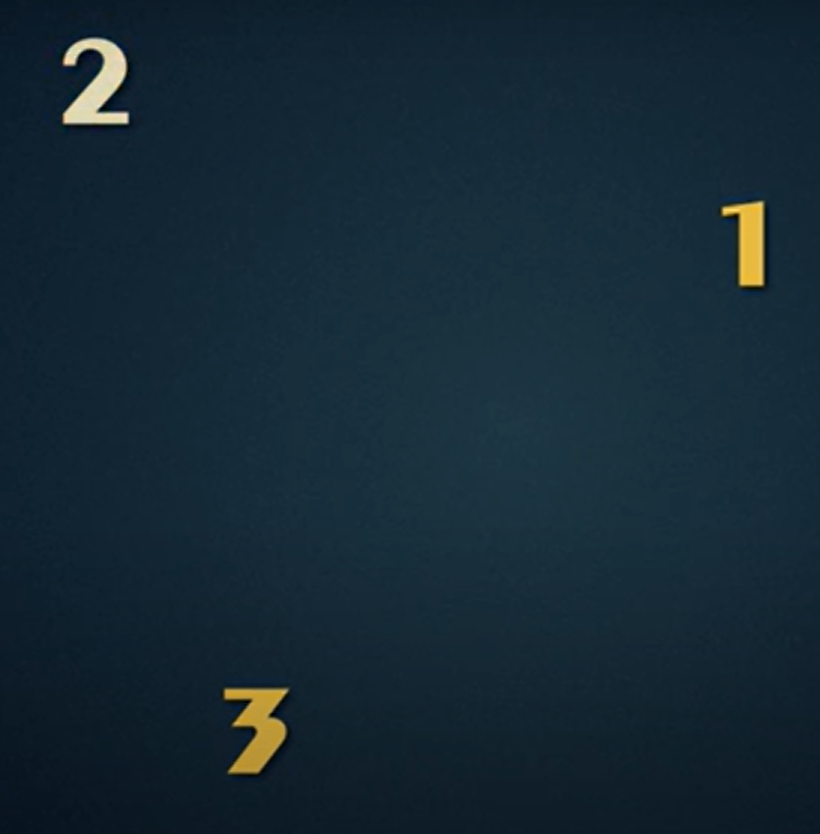

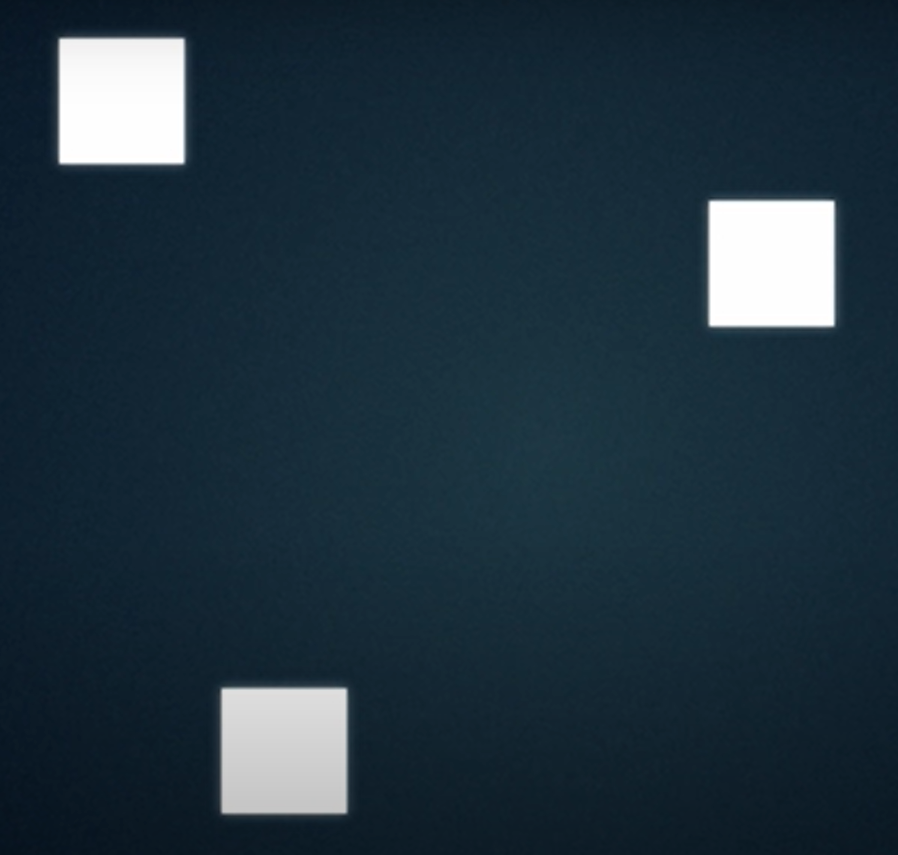

The Primatologist Dr. Tetsuro Matsuzawa has identified a cognitive skill where chimpanzees beat all humans, adult or children, hands down. He has set up a test where a sequence of numbers appear on a TV screen, and are then hidden by a square (see figure below). The person watching the screen has to try and remember where each number is by tapping the corresponding squares in sequence. 1, 2, 3 or 2, 7, 9 etc.

Chimps are generally much better at this than humans.

There are about 14 or so chimps that live at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University, who are invited to play this game regularly. Ayumu, a young male, is the best and current undefeated world champion.

He is able to correctly identify 9 hidden numbers in sequence, after only seeing them for 0.5 seconds. If a normally constituted human is shown a set of numbers for half a second, they will usually be able to correctly remember the position of 3 or 4 at best. Repeating a sequence of 9 digits like Ayumu regularly does, is just impossible.

Compared to a chimp we are just not very good at identifying and classifying what’s right in front of us. Half a second just isn’t enough time for me to recognise all the numbers and remember their positions. Dr. Matsuzawa thinks this is due to some kind of cognitive trade-off.

The “cognitive trade-off hypothesis” hypothesizes that we have traded our ability to actually see what’s what, in favor of being able to imagine and tell our friends what could be. In other words, the parts of our brains dealing with accurate perception and short term memory, may have been atrophied in order to make space for imagination and language.

I think Matsuzawa frames it in terms of a trade off between an accurate understanding of the here and now in order to facilitate immediate action vs the ability to plan and communicate about an imagined future.

Both these comparisons seem to suggest that what really sets us apart from other primates is our capacity for imitation, communication and imagination.

In the experiments where chimps and human children watched someone perform a series of maneuvers in order to obtain a prize, another telling difference occurs. The children will do a good job of copying the whole procedure, regardless of whether any particular act (eg. flipping switches, hand gestures etc) actually affects the end result in any obvious way.

The chimps that are able to solve the puzzle (which usually means obtaining a piece of fruit) after observing someone else do so, will more often concentrate only on what seems necessary. In a certain, non negligible, sense we could argue that the successful chimp has grokked where we have merely aped, copied or integrated.

Imitation, as in the ability to adopt outside knowledge, is obviously a feature of human intelligence, it has helped get us to where we are today. But imitation, as in the mechanical integration of some outside authority, could also be a bug.

Let’s look at exactly what we mean by cultural intelligence, and why we can reasonably call ourselves the first ever cultural species. And in doing so explore the limits that a cultural basis to our experience and understanding of the world implies.