Communication breakdown

On Dialogue was first published in 1990, it starts with the following lines :

“During the past few decades, modern technology… has woven a network of communications which puts each part of the world into almost instant contact… Yet, in spite of this worldwide system… there is… a general feeling that communication is breaking down… People living in different nations, with different economic and political systems, are hardly able to talk to each other without fighting.”

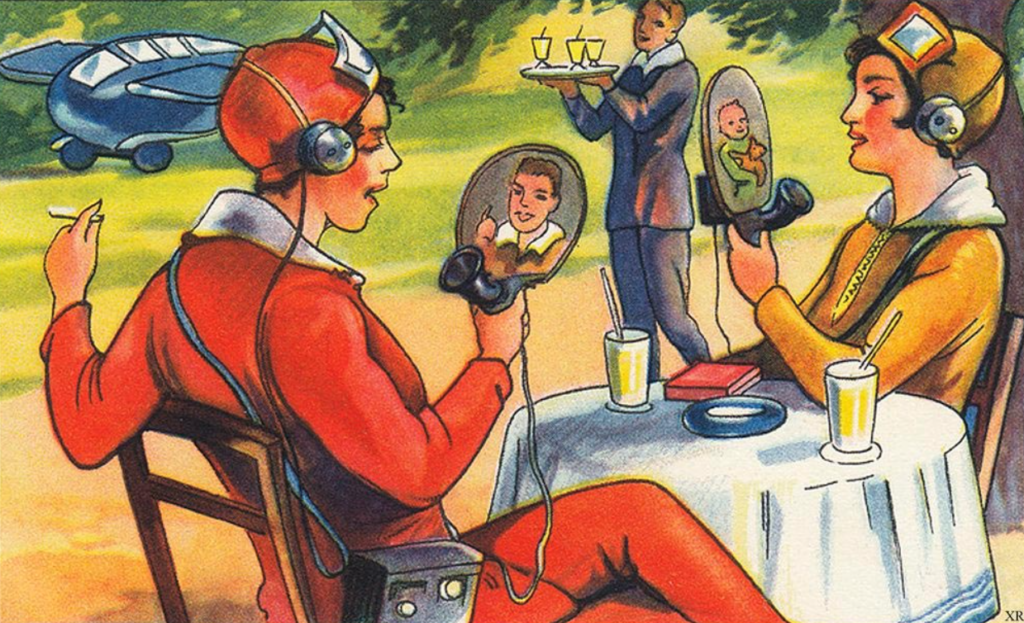

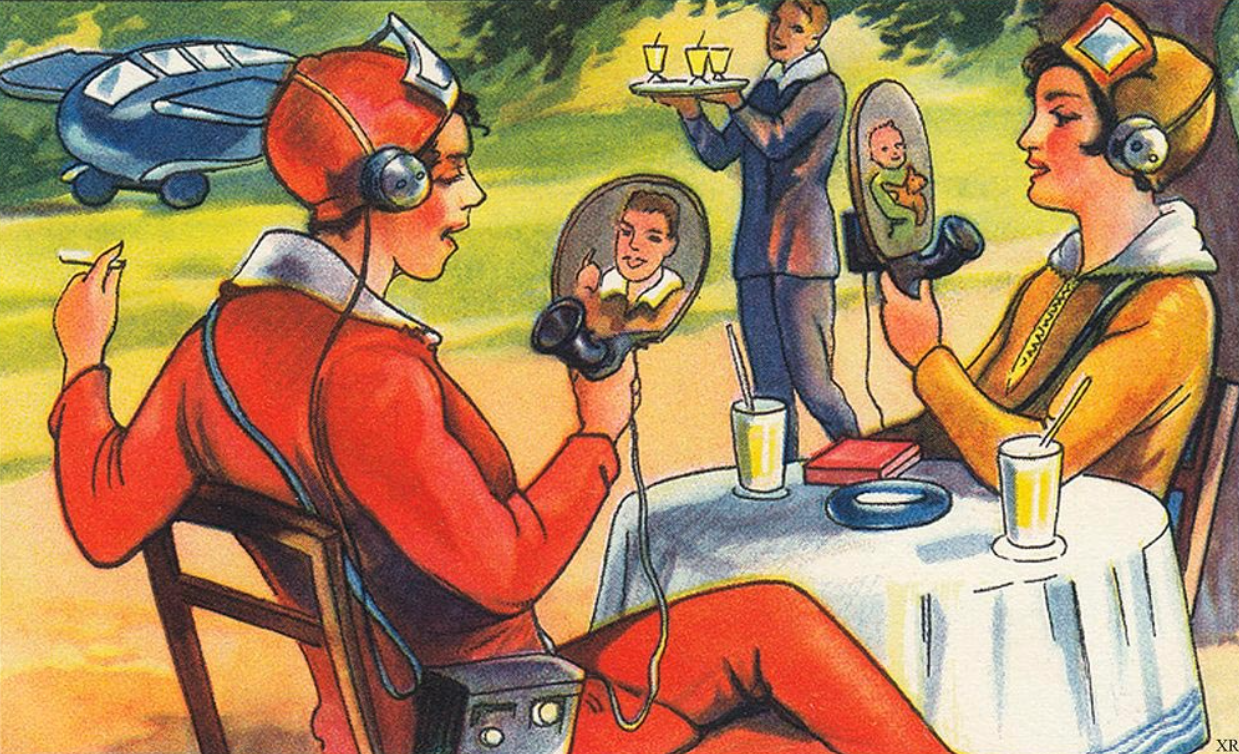

And this was before the internet – Tim Berners Lee was still writing the source code for the world wide web. The new age of Aquarius had not yet dawned. It was still possible to imagine a digital society where free access to information would finally liberate mankind from the shackles of ignorance and stupidity.

By now it’s become obvious that our relationship with information still needs ironing out. Social media posts have been linked to alienation within families and even genocide. The number of believers in Flat-Earth and other weird conspiracy theories is on the rise.

When efforts are made to address the breakdown in communication it becomes obvious that trying to provide better facts just makes things worse. Telling me I’m wrong makes me more defensive. The key to communication is mutual understanding and trust. It seems that we only communicate amongst friends. If you want your enemy to listen, you have to become their friend. Are you ready to befriend your enemy?

Maybe we’re asking too much. What if the person you’re talking to feels like everything that’s wrong in the world. The doctrines they’re espousing sound evil and harmful. How can you befriend someone so dangerous?

Unfortunately the fact is enemies have trust issues, and communication necessarily entails some sort of communion. Communion being an intimate fellowship.

We only truly learn from each other when we’re able to listen freely – without prejudice, without trying to persuade or defend, and without attachment to prior conclusions. This requires a primary interest in truth and coherence.

Unfortunately another fact is : I’m trying to protect myself here. That’s my primary interest. If some idiot is calling for the abolition of vaccines, that might feel wrong and dangerous. If I’m from an ethnic minority and they are racist, they are wrong and I feel threatened.

The structure of conflict

This is where Bohm points to our biological inheritance : the fight or flight response happens automatically. It’s completely normal.

Imagined threats will provoke real physiological responses. If my boss starts criticizing my work, my heart rate will increase. If my cultural identity is being rejected, my shoulders might stiffen. These signs of stress will be accompanied by emotional reactions like fear and anger. Which means I will have a strong desire to act : to flee or to defend myself.

But I can’t just run away when my boss gets angry – I can’t punch someone for mocking my street cred. And whilst I’m stuck there my body is being flooded with adrenaline and other chemicals, like it would if I was being attacked by a lion.

The primitive part of my brain is responding automatically as it has for millions of years – to keep me safe. And the more modern part of my neural cortex that has evolved to create mental concepts and images is also reacting with its own projections. Sadly this mix of old and new comes with compatibility issues.

The older neurological hardware is doing its job of reacting to danger, but it wasn’t built with the capacity to distinguish between actual and imagined realities. The highly developed frontal cortex in modern humans, which is great at producing images and concepts, is also helping to sustain a lot of anxiety. These imagined threats add to the stress. And if we can’t calm down, we have trouble thinking coherently. Our mind gets caught in a vicious circle of panic or anger.

Conceptual models of reality can of course be really useful – they are representations, like maps. We can replay past events, we can imagine potential futures.

The trouble starts when our abstract models are mistaken for authoritative fact. When they affect our emotions and our worldview. The nervous system goes into alert as it reacts to our mental maps – I am forced into action by my own imagination.

Our representations are mistaken for actual external realities. Leading to a paradox where our mental tools for solving problems end up making things worse. Like going to war based purely on our self-image and cultural myths.

It feels like we are heroically tackling real world threats, when we are in fact acting like vicious brutes based on our own twisted vision of morality. What we call problems are sometimes just the symptoms of our confusion between representation and actuality – between the map and the terrain.

Treating the actual problem, rather than merely being a symptom, or part of the problem – requires a wider perspective.

Rather than being carried headlong into battle by our convictions, we need to be aware of this automatic process. We need to be aware of this habitual process of unnecessary violence based on our mental activity.

If we weren’t being totally distracted by the content of thought, we could see that thought is part of a larger process.

Normally I am one of the objects in my experience (ie. me), reacting to other objects according to some set of beliefs. Our actions are determined by our ideas and emotions in a smooth mechanical process.

The process feels totally normal, every part appearing as a neutral or self-evident response to the situation at hand. But the “situation at hand” is at least in part, a mental construct – based on our convictions.

And our convictions can be at odds with actual reality, or with the situation as it’s being experienced by others.

Bohm calls this contradictory relationship with reality : paradoxical and incoherent.

It’s paradoxical to get so psyched out by the problems that we have created. We imagine a problem and then try to solve or run away from what we have imagined.

It’s incoherent that we should be in conflict with our own mental projections – we end up defending identities, beliefs, nations, etc..

How to Dialogue

Dialogue, as defined by David Bohm, is a way of addressing our incoherent relationship with ideas and with each other. It’s a space where our attempts at communication are exposed as a reflection of who we are. By simply paying attention to what happens when we talk to each other, we can see what is actually driving our moment to moment experience. We can see how we are all mechanically driven by our pride, our fears, our prejudices.

The first hurdle in any dialogue is our need to be right. Even those of us that want to avoid conflict are concerned with personal loss and gain : we want to know which belief to adopt.

And so we get caught up in the theorising, the speculation and debate. The goal of analysis and comparison being a winner – either the superior speaker or most attractive concept.

We have to pay attention to our tendency to debate, to argue, to defend our positions. The goal is not to reinforce our worldviews, it’s to see that we are always reinforcing our worldviews. To see that we are all being driven by the same insecurities.

When we first start a dialogue group this is what must be discussed – we have to talk about what we mean by dialogue. That it’s not a debate. That we also need to pay attention to the internal dialogue happening in each one of us.

As the other person is speaking, we automatically get caught up in our own mental reactions. We start comparing what we hear to what we already know. And based on that we start resisting or agreeing – or simply misinterpreting what is being said. Our own inner monologue is diverting our attention.

The aim of dialogue as a form of meditation is a broadening of awareness. That means being aware of our own motivations as they arise. We can listen to the ideas coming from our interlocutor, and also be aware of the ideas arising inside of ourselves.

Once it’s been established that the interaction does not revolve around winning arguments – we have to avoid the second trap, which is trying to avoid arguments.

It’s great if we’ve seen that dogma and violence creates unnecessary pain in our relationships, and that it stifles creativity. But differences of opinions exist. Confronting those differences is sometimes necessary in our everyday lives – for practical reasons. We might need to decide which option provides the best solution at the office or at school. Which class to take, which retirement plan works best, whose advice makes the most sense?

When inquiring into the nature of our relationships, arguments are also useful, they are the nuts and bolt content. They are a window into our inner workings. We’re not trying to pretend that we don’t all hold to different opinions – we’re looking at what that entails.

So what do we do? If we have somehow managed to listen to what someone else is saying, and we have noticed the mental and emotional reactions bubbling up in ourselves – what now?

Suspension is Bohm’s answer. Don’t do anything : neither repress nor express.

We will react mentally and emotionally when faced with ideas. Assumptions about reality will arise unbidden from our unconscious, or our memory, in response to the views being expressed. If it’s an opposing view, our irritation or hostility is directly linked to the assumptions hidden within us.

Suspension is the key practice in response to revelation. In other words : there is no need to move away from insight. We are being encouraged to trust that an awareness of the big picture is sufficient. A clear picture of what the speaker is portraying and a clear picture of my own motivations is already clarity. And clarity allows for intelligence. At least more so than allowing our hidden motivations to blindly lash out in anger at something that we have misinterpreted.

To accept that we (the speaker and I) are both humans – means that we need not condemn, nor justify our human foibles. And by giving our full attention to that shared psychological process, the process need not escalate into violence. Attention helps maintain a safe space for inquiry.

In suspension, thoughts, emotions and bodily reactions can be observed as a single unfolding process.

The danger now is that we confuse careful listening with “talk therapy”. Like in support groups based on shared identity (e.g. women’s or men’s groups, Alcoholics Anonymous, UFO abduction victims etc..) – or Psychotherapy.

It does feel good when our identity is affirmed, when our hopes and fears are being validated by our peers. We feel lonely and a sense of community is a blessing. Being able to express ourselves and be heard is essential for our wellbeing as social animals.

An analysis of our past traumas and an examination of the life that led us to where we are now can also provide immense relief – and even some practical strategies.

But that’s not the point of Dialogue. Our need for validation, our effort to find answers and solutions is part of our psychological makeup. The point here is not to enable but to observe.

Therapeutic healing can occur as a byproduct, our painful existence may be transformed, but that’s not the effort we are being asked to make.

We are being asked to suspend our habitual wants and fears in order to create a space of unbiased observation.

This is not so much about personal development – we are addressing wellbeing from the cultural or human perspective. The object isn’t to solve particular problems, it’s to observe how problems are created.

We are watching together, how people interact in society. Do the units function coherently in their own social environment?

The goal of dialogue is shared meaning. Let’s start with the words – to look together there must be a curiosity about what is actually being said. So obviously I must not be distracted by my feelings about what you are saying. My interpretation, my condemnation or attraction to what you are saying must not take precedence over your actual message.

Instead of immediately agreeing or disagreeing, I can test out different responses – because we’ve created a safe place to experiment. For example, if I am feeling overwhelmed by my resistance to what I am hearing (ie. it feels really, really wrong) – I can stay silent and watch that feeling.

Or if I think that something significant has been said or implied, I can express whatever that might be in my own words. The message is thus restated and enriched.

Shared meaning also appears in our behavior. In which our fundamental motivations are exposed – how we all function in the same way, driven by the same psychological processes. That we’re all, whether friends or enemies, in the same boat paddling in the same direction. We’re simply on different sides, we’re from different tribes.

In this space, free from personal concern or cultural bias, shared meaning becomes apparent. And thus we can act in the light of what is seen. There is an opportunity for intelligent action.

If we see the simple fact that we are similar organisms, with similar brains – being driven by the same fears and desires – the possibility of coherence emerges. We are able to work together towards what we both want.

And if we can inquire into the truth of what we believe together – the possibility of communication emerges. We can understand what is being said.

Coherence and community

In this communality of mind and being – conflict and fear is no longer the driving force – the notion of enemy or outsider loses its authority. We don’t have to attack foreign agents, or defend against their foreign ideas. From coherent thought a coherent society naturally emerges. A community without outsiders.

Which is not the same as everyone adopting the same ideology, or accepting every belief as true. The point was never to impose opinions or to agree on which idea was the best. Dialogue was never about winning, no one idea or person is meant to prevail. It was about allowing meaning to flow among and through us, so that a shared understanding might emerge that was not present at the start.

It’s not about accumulation or conclusions, but allowing the habit of clarity to arise from observing together.

Normally we engage with opinions on the basis of identity or possession, as in my opinion and yours, and treat them as being radically different. And thus we feel obliged to judge, compare and oppose ideas and identities as separate or disparate entities.

But now, with a broader perception of how ideas, emotions and identity arise – there is less confusion. This is what David Bohm calls “proprioception of thought” – in reference to proprioception : awareness of our own body in space. Here he’s hoping for increased sensitivity to the source, movement and formation of thought.

Beliefs are no longer “mine” or “yours”, we don’t create them. They are tied to language and culture, they are passed on via our institutions and through the media.

The individuals that make up the “us” and “them”, are local expressions of a larger movement of culture and biology.

As these feelings of possession and dissociation are allowed to fade – a sense of community can emerge. Shared meaning makes possible a community that does not depend on hierarchy, authority or exclusion. As defensiveness softens, communication deepens, giving rise to fellowship, and a sense of coherence with the whole.

Bohm points out that social cohesion and communication of this type already exists in traditional non-hierarchical communities. He’s alluding to community meetings in hunter gatherer tribes, where information is shared but where no one has the power to impose.

Our sense of isolation, the need to defend our positions is not always active. It’s not impossible for modern humans to feel a sense of connection, or wholeness – it happens regularly. I don’t always have to feel shy, or anxious or somehow at odds with my environment.

Faced with a sunset or a log fire at the end of a long day, my sense of self – with all its needs and worries – can subside. I don’t always have to be on alert, fighting for survival, trying to progress, protecting what’s mine.

We are a thinking, feeling, social species – it’s about time we learnt to live with human thoughts and feelings.

Faced with the ideas and emotions arising in me or in others – what do we do? Anxiety and resistance are not the only option – they are often the worst. Judgement and comparison automatically arise from our need for safety and progress – we miss out on simple appreciation. If our experience is always focussed on self-concern, a whole palette of life is lost.

Fellowship, discovery, wholeness, beauty, creativity are not found in fear – though they may be what makes a life worth living.

Leave a Reply