“I think that tastes, smells, colors etc. reside in consciousness. So if we disappear, all these qualities would be annihilated” Galileo Galilei

Donald Hoffman, a cognitive psychologist who studies consciousness, begins his book The Case Against Reality with this quote from Galileo. Hoffman’s thesis is that our conscious experience of spacetime and the things within it is a creation of the brain. So far so good, 9 out of 10 neurologists agree.

We also generally agree that our experience of reality is not an exact representation of reality as it actually is. This becomes obvious if we consider the atomic theory of matter – matter consisting essentially of empty space and the interaction in that space of tiny subatomic particles – we don’t experience reality as such, we experience rocks as rocks.

The jewel beetle’s delusion

Dr. Hoffman likes to illustrate his point with a story about the Australian Jewel Beetle, which serves as a cautionary tale about the existential dangers of preferring beer over women :

Jewel beetles are shiny, dimpled, mainly copper coloured insects that live in the Australian outback. The males spend much of their time flying around in search of females in order to make babies.

Aussies are the indigenous, “no-worries” humans that also like to visit the outback. The males spend much of their time drinking beer, and often leave the empty, shiny, dimpled, copper coloured bottles (aka “stubbies”) lying around to mark their passage.

Now, when a male beetle spots one of those glossy stubbies lying on the ground, he sees irresistible beauty – and immediately alights upon the bottle to do his duty for the species.

Unfortunately, despite the stubby being huge, amazingly glossy and incredibly dimpled, in short despite appearing to be the sexiest thing ever, all the valiant efforts of our male beetle are in vain. No babies are born of this union, and our exhausted, starry-eyed bug usually ends up as food for the local ants.

This became such a problem that local wildlife enthusiasts ended up sounding the alarm : the Australian Jewel beetle was in danger of going extinct. And, in maybe the most astounding and heart warming part of this story : Australia rose to the call. Laws were enacted, stubbies were redesigned, littering was frowned upon and the jewel beetle was saved. Huzzah!

The key point in this story of unrequited love, is that what the bug sees is a delusion, is completely false.

Evolution has provided the jewel beetle with the senses necessary to find a mate – to recognise reproductive potential when he sees it. He thinks the stubby is really hot, but he’s wrong – it is demonstrably not.

There are other examples of this kind of thing happening : Swans preferring to sit on footballs rather than their own eggs; fish swallowing a fisherman’s lure, hook, line and sinker etc..

And if other animals can be fooled by their eyes and ears, surely we can too.

Dr. Hoffman’s position is that evolution has provided us with “life hacks” for survival, which have nothing to do with perceiving the truth. My attraction to beer bottles has nothing to do with my understanding of what beer bottles really are. I want beer, the fundamental nature of beer bottles is irrelevant.

Error propagation

As a cognitive scientist, his goal is to solve, or at least make some headway into the “hard problem” of consciousness. Namely : explaining what consciousness is, how it works, why we have conscious experiences.

Seeing as we don’t seem to be making any headway into the question, despite decades of research and tons of data about how the brain works, he suspects that we must be doing something wrong. We might be barking up the wrong tree.

In this case, the big mistake we (meaning neuroscientists and cognitive psychologists) are making is : believing our eyes.

Eureka? Of course! It makes sense : if my eyes are lying to me about beer bottles, then they must surely also be lying to me about brain cells, neurons and synapses.

And if our base observations are even slightly wrong, then any assumptions based on these premises have a good chance of getting wronger. (and wrongerer)

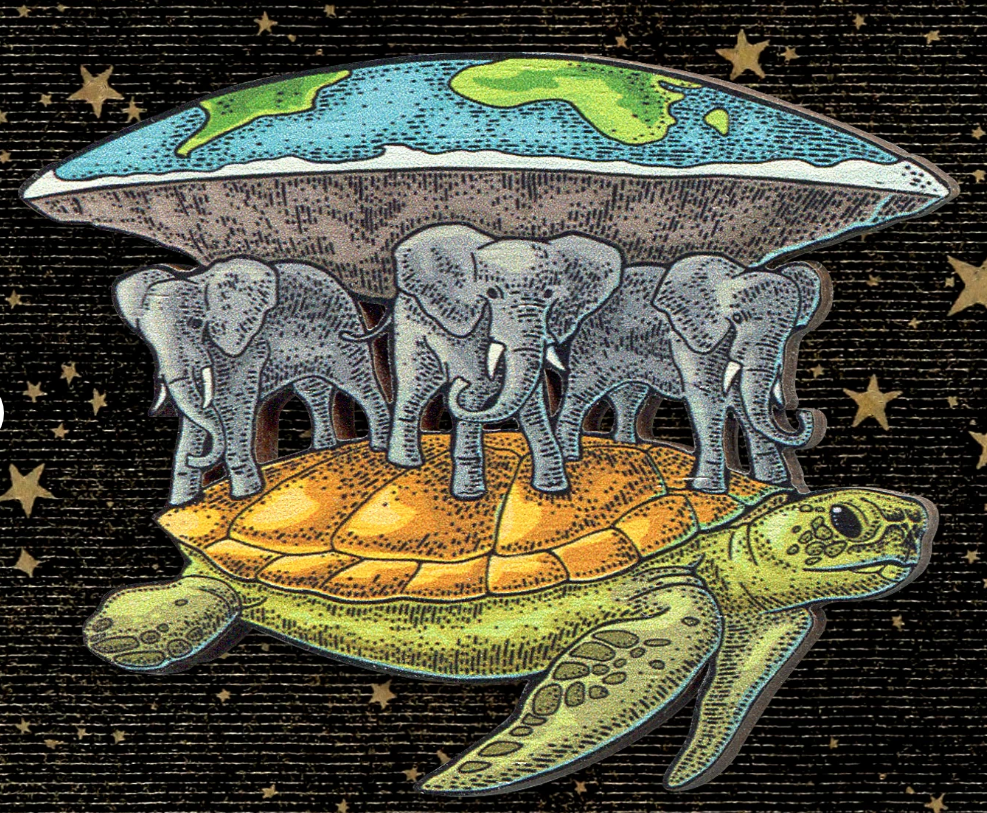

For example, if I assume the Earth is a disc, because it looks flat to me, there is at least a 50% chance that I might be wrong. In order to explain gravity (ie. why things fall to the floor rather than just float in the air) I could assume that the discworld is rising upwards like an elevator. And in order to explain why the oceans don’t just spill off over the edge, we could assume the existence of some kind of perimeter wall.

Merely by adding assumptions to my initial observation, I am also multiplying my chances of being wrong. If there’s only a 50% possibility that this is a disc world, then statistically, due to the rules of uncertainty and error propagation, a rising disc world is less probable. A rising discworld surrounded by an ice wall even less so. And by the time we’ve assumed that the disc world is being carried on the back of a giant turtle, our chances of being right might be zero (or less – I haven’t actually done the math).

So, says the good Doctor, trying to discover how consciousness arises, by looking through microscopes and making assumptions based on our sense data, is a bit like sending an expedition to the outer ice wall in order to lower someone down over the edge in a basket. Our chances of getting a good photo of the giant turtle are slim.

If our conscious experience isn’t a reliable indicator of truth, then we can’t rely on it to find out what’s true.

Questioning authority

Luckily, we still have stuff like math and logic, against which we can test our assumptions. And that’s what we will be presenting in the next chapter : The Case against Reality. Which basically argues that our experience of reality is in no way an accurate reflection of reality as it actually is.

Dr. Hoffman does a pretty good job of that, but still has a long way to go. His conclusion seems to be that in order to understand consciousness, we need access to reality at a deeper, more fundamental level. This is based on the, unfortunately unproven, assumption that consciousness is somehow more fundamental than its contents.

He says stuff like : “spacetime is doomed, we have to go to a much deeper framework”.

Good luck to him – physicists are definitely making claims and predictions about our universe that are way outside the purview of our biological sensory perceptions, and the common sense opinions derived from them – so maybe cognitive psychologists can do the same.

My goal in presenting his work is somewhat different. The realization that I do not normally have access to the truth, the solid indisputable facts, or whatever, may be useful in itself. I’m not so much interested in discovering ultimate reality, and more about avoiding acting like a jerk.

If I am right, and you are wrong, then maybe our conflict is justified? If what I believe is true, and you are questioning my beliefs, then maybe it’s okay for a bit of righteous anger? But if we’re both helplessly projecting our subjective, cultural conditioning – me believing in my own opinions and you in yours – then maybe outright war is an unnecessary, cruel mistake?

My experience of reality feels really, really real to me. Hoffman is offering us an opportunity to question our experience, to question its seemingly unquestionable authority. He’s offering us a change of perspective, an opportunity to broaden our horizons, open our minds – a bit like a school trip abroad for teenagers.

Of course it’s essentially a philosophical, or virtual trip abroad.

But it’s a trip to a very, very exotic place. It’s a frontier beyond our current relationship to weird questions like : “If a tree falls in the forest with no one around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

The accepted answer is usually that “sound” is the auditory experience created by our brains – which of course can only occur in the presence of some brainy person with ears.

We still feel very confident that “sound waves” still exist, that they are vibrating through the air. We stand firm in the obvious knowledge that the tree exists (we can see it, point at it, touch it) – that it really did fall.

Unfortunately, Hoffman is forcing us to be honest about the full implications of what we are saying. He is not allowing us to get away with logical contradictions.

If we accept that sound is an experience created by our brains, on what basis do we insist that soundwaves, air, trees and even ourselves are any different? How is our experience of these things or concepts any different from our experience of sound? Aren’t they also products of our eyes, ears, touch and brain?

Well obviously they are. Hoffman’s not even asking that question, he’s too busy demonstrating that our experiences are just useful delusions at best.

Anyway, let’s get into it. Keeping in mind that this is supposed to be science. By which I mean it’s not just speculative philosophy. Dr. Hoffman can only succeed if his hypothesis is backed up by evidence. And since science is an unforgiving taskmaster, he must also address any evidence against his claim.

Leave a Reply