Amalgamind

Our minds are not confined to our brains. Or more precisely our knowledge or intelligence is not solely dependent on our brains. Think Encyclopedias, Libraries, Google or even your mum. That’s what we mean by “cultural intelligence”. In order to deal with any given problem, I’m not limited by my own memory or analytical abilities. I can ask someone else.

Of course, we did not become the “first cultural species” by magic. Humans are part of a long evolutionary timeline. Many other social species also display proto-cultural tendencies.

Imagine if you will a 50 year old elephant named : Endugu. She happens to be the leader of a herd in the African Savanna. She is also the only member of the herd who was alive during the great drought of 1978. 1978 being the only time Endugu visited a particular watering hole situated outside her habitual stomping grounds. And thus the only one capable of leading her group to this life saving place in case of need.

If I can use the memories in someone else’s brain to help me survive, or generally deal with everyday situations, this is the beginnings of culture.

Language is probably one of the key foundations of culture. So if we can identify (and we can) some primates who are able to communicate vocally, ideas such as : “alert! danger from the sky!” or “me got yummy!”, that would be another proto-cultural spark. Because, here again we are acting on knowledge in someone else’s brain.

The evolutionary leap that we’ve made, in comparison to Elephants or Monkeys, lies in the fact that data can be stored outside of brains altogether. Thanks to the level of complexity of human language, and the invention of writing. We can share what we know in books.

Cultural intelligence is very similar to the concept of “extended cognition” or “extended consciousness”, proposed by David Chalmers or Andy Clark. They posit that cognitive processes can extend beyond the boundaries of an individual’s physical body. Meaning that we can rely on external tools like smartphones and universities, to aid our cognitive processes, effectively expanding our minds beyond the brain.

Big is Beautiful

The theory of cultural intelligence also includes the notion that any one person’s “Eureka” moment is never a solitary endeavor. Each person’s perspective, every invention and any discovery, always happens as part of a broader cultural framework – as part of a dynamic network of data storage and dissemination.

Take for example, the invention of the bow & arrow. Did loads of people, across different times and places, independently invent this excellent technology? Or was it invented maybe once or twice during our 200000 year existence?

What if I tell you that the earliest evidence of arrows are some 65000 year old broken stone points? So if these fragments really are bits of arrowheads, it’s fair to assume that homosapiens existed for around 130000 years without managing to invent this really useful tech.

We are trying to demonstrate that Tech use is dependent on culture. That people are not regularly reinventing stuff because they are so clever, but rather that we are exceptionally efficient disseminators of the rare sparks of creative insight that do occur.

We are saying that society is a kind of collective brain, and as such is capable of far more creativity and knowledge than any specific person’s individual brain. And moreover that larger and more interconnected populations generate faster cumulative cultural evolution and can sustain more complex technologies.

If this were true we would see that bigger tribes have more tech. And vice versa.

The Tasmanian Aborigine is a commonly cited example. Known for having one of the smallest cultural toolkits of any society. For a while it was even thought that they had forgotten how to make fire. But this is now contested. However, if we compare Tasmanian tech (eg. hunting equipment, clothing materials, fishing gear and canoes) to what their cousins on the Australian mainland have got, the insular clan is found wanting.

This is in line with the idea that the smaller, island population lacks the quantity of cultural connections necessary for the preservation and improvement of knowledge. The 8000 years that they were cut off from the rest of Australia, by the rise in sea levels, was enough to make the difference in their toolkits apparent.

The Polar Inuit culture of Greenland is another case that illustrates the same point. Between the years 1820 to 1862 they came dangerously close to extinction due to the loss of essential skills. By a cumulation of unfortunate events, ranging from a flu epidemic to extreme weather, and a drop in food resources, everyone that knew how to build a hunting canoe, died.

And despite everyone else realizing how important hunting canoes were to their continued survival, nobody was able to reverse engineer one.

The reason Polar Inuits still exist today is mainly thanks to contact and cooperation with the Inuits on Baffin Island, situated 500 km to the west.

Okay, let’s just make sure the terms and the thesis are clearly defined :

“Culture” refers to the ideas, customs and social behavior of a particular society.

“Intelligence” is the ability to respond adequately to a given situation.

And it is culture that supplies humanity the appropriate means to respond intelligently. The more people in a society the more novel events will occur – via misunderstandings, mistakes, force of circumstance etc. The more connections between those people the more data will be distributed throughout the system.

Large interconnected groups generate more tools and know how – as the Tasmanian and Polar Inuit stories seem to demonstrate.

And the size and connectivity of the community is far more effective in terms of creativity and accumulation of knowledge than any one person’s IQ (or GI: General Intelligence). A large gang of communicative dumdums will outpace a small clique of introverted eggheads.

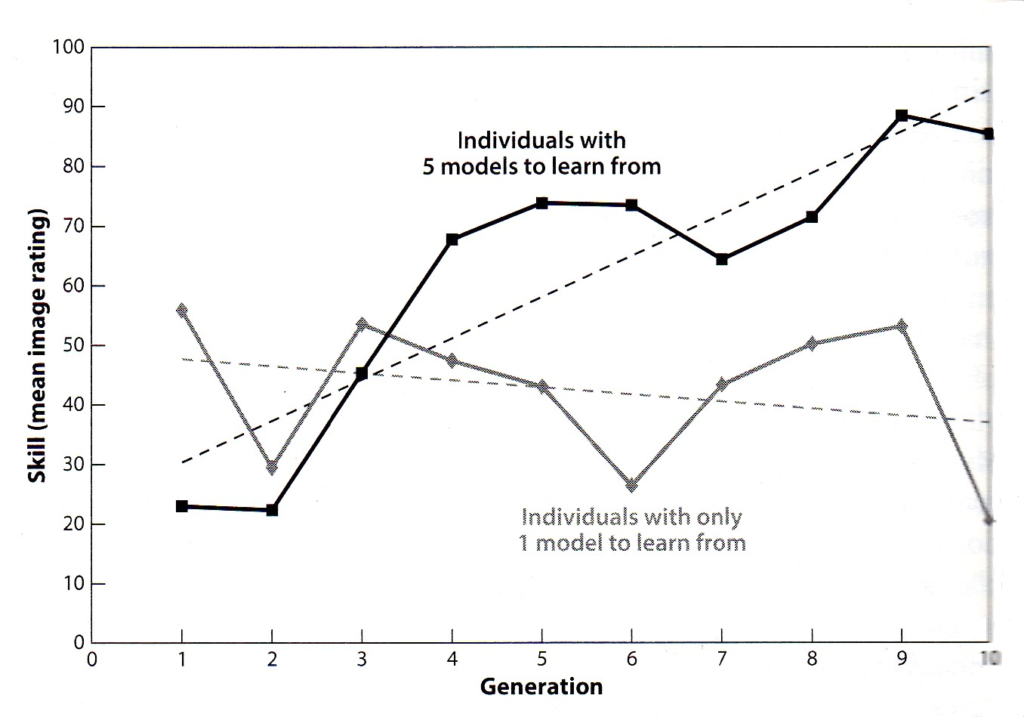

Dr Henrich demonstrates this in the figure below (with his student M. Muthukrishna) : it basically shows the level of skill over time depending on whether you could only depend on one expert explaining a certain procedure, or whether multiple individuals explained it to you. The more people you know, the higher the quality of data accumulated. Probably because no one person is going to be able to pass on 100% of what they know.

Belief & Identity

So we have stumbled down a unique evolutionary path that relies on a brain that instinctively imitates and integrates the words and deeds of the people around us. We are even willing to overrule our own experience and intuitions to do so. Take chilis for example, they are an integral part of many traditional cuisines, despite the fact that their main contribution to the senses is pain (and I love chilis, I’m planning on testing out a fermented strawberry/chili vinegar recipe asap).

We have also developed an innate attraction for individuals bearing the hallmarks of success, precisely so that we might learn from them.

And finally, we’ve pushed the social instincts of living together in groups and creating relationships to new heights (Think Tokyo, 39 million inhabitants. Or Facebook, 3 billion users monthly).

These 3 cognitive adaptations : imitation, fascination with success and desire for connection, are what seem to be the major driving forces of our ability for rapid cultural and technological accumulation and change. In big cities, fads and gadgets come and go in the blink of an eye. Hula hoops and fidget spinners might have faded from the scene, but they will be forever in our hearts, and encyclopedias.

Some clues that these 3 cognitive processes may be at work in our societies are things like:

- How our religious beliefs are correlated to our place of birth – because we integrate what we hear and see around us.

- Respect for our elders – because managing to survive into old age has long been considered a sign of success (success at surviving, traditionally seen as a win).

- Popstars selling cars or influencing votes – because the prestige gained in one domain now affects our perception of their authority generally.

- Tribalism – Or how conflict & “truth” can be affected by groupthink, due to the importance of our relationships.

Not only is Culture the basis of human intelligence and knowledge, but it is such an important part of how we operate that it has also affected our physiology, our psychology and our identity.

Take our small teeth and short colon (compared to other great apes). This is probably due to the fact that homosapiens are the only species to cook their food. And we have done so ostensibly throughout our 200000 year existence. Culture has shaped our bodies.

Take the Kuuk Thaayorre Aborigines of Australia, who don’t have words for left and right. They’ll say stuff like : “I like the earring you’re wearing on your Northern (or Southern etc) ear”. Their traditional greeting is “Hi, where you heading?” (instead of “Good morning”). To which you should reply “I’m heading West” (or NorthEast etc depending). This has led to these people having a sense of orientation on par with some migratory birds. Something that was long deemed impossible due to our lack of specialized sensory apparatus. But in fact evidently very much possible. An ability provided by a cultural quirk.

Specialization is another aspect of our behavior that sets the cultural species apart from the purely social animal. We can devote our life to one particular idea or activity, thus helping our society flourish and in turn flourishing ourselves. We even identify ourselves by our specialist occupation (eg. butcher, baker, candlestick maker etc).

The biggy is probably how language and a theory of mind (ie. the capacity to deduce someone else’s mental states based merely on their behavior) seem to be genetic or epigenetic traits. Infants, from around the age of two, are instinctively able to ape the complex musicality of their mother tongue. They seem naturally able to ascribe intent to their peers.

So tangled is this net of behaviors and abilities that we are faced with a chicken & egg dilemma – which came first? Language : the ability to insert ideas into another person’s brain; or Culture : communal beliefs and behavior?

Resistance

All these traits and behaviors are so far removed from any other form of life on Earth that some folk are claiming that we’re a new kind of being. Culture starts with us – we are a new form of intelligence. Culture can be seen as a major shift on the evolutionary timeline. Nearly as significant as the apparition of biology from the primordial chemical soup. On par with the advent of rudimentary brains in primitive biological organisms.

Anyway, even if you find the idea a bit far-fetched, the shift from individual smarts to cultural know-how is a planetary first. Human intelligence is based on a superorganism, known as Culture.

On the one hand Culture helps keep us alive, it is the motor of progress. Thanks to the bicycle – a much loved cultural artifact – we have gained the ability to move as effortlessly as the Albatross gliding on an ocean breeze . Hallelujah!

But what’s the flip side? If what we call Intelligence is merely a form of imitation and belief, what does that imply?

Well, obviously there’s the danger of believing in stuff that’s not true.

Whether something accurately describes an aspect of reality, does not depend on who is telling the story, or how many times I hear it. But apparently that is exactly what seems to confer authority to what I believe : whether I trust the person telling me the story, and how prevalent the story is in my life.

If my parents or my friends believe something, and people I respect on TV or the internet are constantly repeating that same thing – odds are I’ll end up believing it too.

There is an automatic principle of authority that accompanies all the narratives that become part of my world view. By which I mean that everytime I adopt a new belief, it automatically takes on an aura of rock solid truth. I automatically feel that I have gained some accurate understanding of the world around me. This holds true even if my understanding is that thunder and lightning is produced by Thor when he explodes the Frost Giants with his mighty hammer.

Strangely enough, mistaking the stories I believe for an understanding of reality isn’t necessarily problematic. It usually works out just fine, so long as everyone else I interact with also considers these same narratives as true. Believing that Thor causes thunderstorms only becomes a problem if I am a meteorologist, or if I need to predict the weather accurately.

Problems only become apparent when we meet people with a different worldview, with brains molded by a different cultural regime. For example, when a Republican has to listen to a Democrat. Or if our worldview comes into conflict with our goals. Like the meteorologist who worships the Norse gods.

We resist. Our beliefs seem so true. And if they are brought into question we get agitated, lose our cool. Rather than question a story that I identify with, I shall resist. It’s automatic, I can no longer listen when one of my pet ideas is being shoved around, I must defend the truth (or what feels like the truth). How deep it cuts. How can listening to a story hurt so much?

Time to visit Julien d’Huy and the oldest stories in the world. See you in the next chapter.

Leave a Reply