Regress?

With fire, being a practically unlimited source of energy, and pointy sticks, human beings became the kings of the jungle – or the grassy plains. Yet humanity’s drive for progress never stopped. Being top dog was apparently not good enough. Over the millenia we have gone from hunter gatherers to pen pushers (or keypad clickers). What is it about us that fuels this journey from living off what nature provides to walking on the moon (or splicing genes)?

Would it be correct to assume that our commitment to progress is a psychological imperative? Is the need for improvement a fundamental part of our psyche?

This constant striving for improvement can sometimes seem paradoxical, or counterintuitive : just consider one of the first major societal advancements in human (pre)history, the shift from our nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle into agriculture.

Surely to progress is to move from a state that is somehow inadequate to something that is somehow better. This is of course a value judgement. The idea is that we are not satisfied with the current situation, and thus make an effort to improve it.

With hindsight we can question whether our transition into an agrarian society was actually progress at all. The archeological data seems to indicate that the first Neolithic farmers had to work a lot harder and were much less healthy than their primitive huntergatherer neighbours (eg. skeletal remains symptomatic of increased nutritional deficiencies and repetitive strain). Granted, we are able to make this comparison with our birds eye view of the data: more effort for a lower quality product (at least in terms of nutritional value) seems like an obvious mistake.

Needless to say, the subjective viewpoint of the average Neolithic person in the field was probably very different. For one thing, the change did not just happen overnight. There was presumably a time when nomadic foraging groups discovered that they could supplement their access to certain foodstuffs by giving nature a helping hand – for example by setting fire to all the weeds, and allowing certain pioneer plants to flourish (like delicious nettles or blackberries).

Any tendencies for sedentarisation would also have been encouraged whenever any tribes happened upon some particularly bountiful ecosystem. Cultural evolution would of course build upon each successive generation’s knowhow for managing and encouraging the local flora and fauna. Progress, in this case, being not so much a choice, but more of an inherited practice. Also, in lieu of leisure and food quality, agriculture probably did provide a relative benefit in terms of the quantity of food produced – and thus for the opportunity to feed more people, which of course means demographic growth. Farmers rule, because they multiplied and took over the land

Genesis

This early step that we took in our ongoing quest for betterment – the first major advance in our shared history of cultural revolution : the move from nomadic hunter gatherers to sedentary farmers, which apparently happened around 11000 years ago, seems to have left major traumatic scars on the human psyche. I say this because we are (unconsciously) still being affected by that move even today. A large proportion of the present-day population still believes in a peculiar interpretation of an early theory we had about our relationship to progress-known as “Original Sin”. I know right: WTF? Please let me explain.

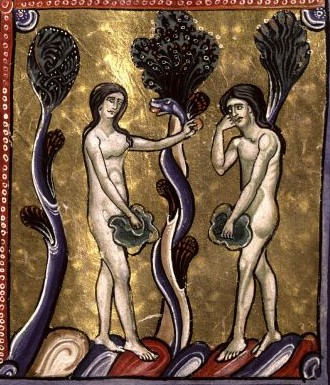

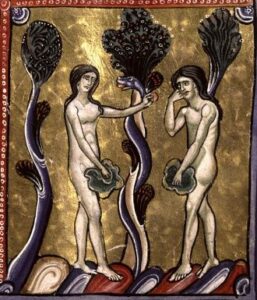

The Genesis story in the Old Testament was probably written somewhere around 3000 years ago. The story includes an explanation of how humanity essentially went from a carefree, day to day existence, happily living off the bounty of nature, to an existence of drudgery and effort, where sustenance could only be obtained through “painful toil” and strife. I am, of course, referring to the tale of Adam and Eve’s fall from grace.

This is basically Iron age man speaking to us, from across the centuries, with their explanation of what it means to be human. It is the account of the farmer described above from their own point of view. As an aside, we may wonder where they got this idea : that their ancestors, the original humans, had lived a more bountiful and leisurely life than theirs. Was this just a coincidental fantasy that simply happens to align with current archeological hypotheses? Or was there some cultural memory of the fact that had managed to survive, that had been passed down through consecutive generations? This question is something that will be addressed later as it ties into any definition of human intelligence, in which cultural heritage seems to play a major role.

Anyway, back to our story of Adam and Eve : Apparently there was this tree that grew in the Garden of Eden, called the Tree of Knowledge of Good & Evil. Despite being a restricted tree by divine command, and I quote : “of the tree of the knowledge of good & evil you shall not eat…”, Adam and Eve – the first humans, who had up till this point been living a carefree day to day existence upon nature’s bounty-decide to eat one of its fruits. This immediately results in a sense of self-consciousness for our two protagonists – the Bible narrative describes them as suddenly realising themselves to be naked. God, who wanders by not long afterwards, informs them that the eating of the fruit of knowledge of good and evil also means that their existence has now become one of conflict, distress and hardship. With this ends humanity’s life of ease in the Garden of Eden.

In the Christian tradition, this story is usually interpreted by focussing exclusively on the idea of obedience. The message being that Sin, which means a failure to follow God’s command, can be extremely detrimental. Usually the events are described thus: God, upon seeing that Adam and Eve have disobeyed His orders, decides to punish them and all their descendants-for ever and ever. We are left with the understanding that suffering is due to an error that happened in the past, and that it is basically dependant on God’s nature or will. His insistence on being obeyed, His anger, His mysterious sense of justice.

Suffering is due to an act of God, a punishment for our failure to follow orders.

It’s an excellent allegory, and if we are to believe this interpretation, human suffering is a consequence of our relationship with an angry deity.

This interpretation is usually attributed to St. Augustine, who placed the onus differently in that it was humanity’s sin (ie. disobedience of God’s rules) that tainted future generations with evil.

Wherever we place the blame, this interpretation, is just a guilt trip. It is basically a tale of crime and punishment that happened long ago, in a faraway place. It is completely useless in that it gives us no understanding of what makes us tick, our modus operandi, no predictive tools (apart from this idea that we must obey a silent deity, which may be predictive, but which remains unverifiable) – we just suffer the consequences.

However, if we parse the story down to its simplest form, we are left with a surprisingly modern idea : Suffering arises from the knowledge of good & evil.

Modern in that it’s an equation posed in purely psychological terms. It reminds me of something that would not seem out of place in an Evolutionary Psychology workshop. Again, hard to tell if this is a coincidence, or whether these iron age philosophers just happened to be ace psychologists, on a par with their contemporaries like Pythagoras in Greece (530 BCE) and Buddha in India (540 BCE).

Clearly, this idea that suffering is a function of discrimination and preference, has been completely ignored by the religious Christian tradition. But does it make sense? Does it align with reality?

Firstly, suffering needs a reference point: the person suffering. Without the sense of some central figure interacting with reality, the concept is meaningless. This is basically our sense of self: the feeling that we are the central agent upon whom reality is being brought to bear. We are the central figure, somehow apart from, but to whom reality is happening.

This may be why the Bible story references the sudden awakening of self-consciousness in Adam and Eve.

The notion of good and bad also needs a point of reference; and here again this function is filled by the self. Neither good nor bad can exist in a vacuum-the same goes for up & down, big & small and, dare I say, past & future? They only exist as differences relative to a point of view. And in the case of preferences or value judgements such as: good & bad, they only make sense in relation to a goal. In this case the survival (or progress and security) of the self. (Or the will of the Almighty, in relation to our souls – being the concept of some enduring, eternal self)

distress

In modern psychology, the sense of self can be understood in evolutionary terms as part of the survival instinct, arising with the need for a central figure that reacts to danger (bad) and security (good).

This might be a good time to mention the similarities with the Buddhist version of suffering, which is also seen as a function of desire, aversion and the Ego/self. Some Buddhist teachings also define the self as an emergent property of our localised processing of sense data. (Skandha)

Knowledge of good and bad is basically a relationship with reality based on discrimination.

When I consider the world around me, either I find it inadequate in some way – too uncomfortable, too dangerous – and I am obliged to do something about it, or it happens to be a wonderful moment, and in this case I want to do my best to keep things as they are. Of course, there are also times when the discriminating self disappears, and with it all notions of good, bad, struggle, conflict or effort. Like for example when we are totally engrossed in our favourite movie, or fully committed to some activity.

But whenever I do consider my situation, or the situation of my loved ones, I will find it wanting in some way. And whatever I consider to be good or precious, I will want to protect.

Whatever I deem my situation to be, it will be a source of concern. This perception of our situation as always being somehow unsatisfactory, is why we have ended up walking on the moon. This constant drive for progress and security is humanity’s suffering self at work.

contrast

Our cultural and technological progress is an amazing achievement. Where would we be without running water, the washing machine and human rights? (most probably : smelly, itchy, tired and kowtowing to our bigger,stronger neighbours)

However, if we apply our magical fruit given knowledge of discernment to our journey of progress over the millenia, a couple of interesting paradoxes seem to crop up.

Take for example our hunter gatherer friend and their spear. At one point in time the mightiest weapon available.

Now consider the atomic bomb. Thanks to our constant effort over time, our internal imperative for progress and security, we have produced something far, far superior to the spear. Or is it far, far worse?

The atom bomb can be described as the ultimate weapon that has by its very power, imposed world peace – but at the same time made it possible for us to exterminate human civilisation at the mere push of a button. So progress or huge mistake? There appears to be some debate on the issue.

We can also ask what progress means when we evaluate the hunter gatherer lifestyle against our own. Consider the office or factory worker. Or a health care provider, a cook, a waiter, a restaurant owner, an engineer, an architect or a carpenter… There are of course strikingly obvious differences between then and now – but which is better? Opinions will once again differ.

This question can only really be addressed by focussing on intent and consequence. Has human suffering been addressed by our efforts to escape it? Have we finally stopped worrying about what tomorrow may bring? About my security and happiness, or the security and happiness of my loved ones?

Hunter gatherers still exist in the world today. Am I happier than a Hadza man out in the bush with his bow and arrow, tracking some prey with his gang? Am I any less prone to worry and sadness?