Ecce est percipi

N'avons-nous donc pas fait fausse route ? L'idée que les choses n'existent que dans notre esprit n'est pas juste - elle semble remettre en question la solidité du sol même sous nos pieds. Cette même frustration se retrouve chez Samuel Johnson lorsqu'il donne un coup de pied au rocher.

Voici comment son biographe, James Boswell, se souvient de la discussion qu'il a eue avec son ami à la sortie de l'église, un dimanche de 1763 :

Nous avons discuté pendant un certain temps de l'ingénieux sophisme de l'évêque Berkeley pour prouver l'inexistence de la matière et que chaque chose dans l'univers est simplement idéale. J'ai fait remarquer que, bien que nous soyons convaincus que sa doctrine n'est pas vraie, il est impossible de la réfuter. Je n'oublierai jamais l'empressement avec lequel Johnson répondit, en frappant du pied avec force contre une grosse pierre, jusqu'à ce qu'il en rebondisse : "Je la réfute ainsi".

Ce qui était réfuté par la douleur qui lui traversait le pied était le principe d'immatérialisme de l'évêque Berkeley, à savoir que "être, c'est être perçu" - ou "esse est percipi" en latin (parce que les trucs intelligentes s'énoncent mieux en latin).

L'affirmation de Berkeley selon laquelle "tout ce qui est imperceptible n'existe pas" semble être une pure baliverne - je veux dire quand les trous noirs ou les atomes ont-ils commencé à exister ? Quand leur existence possible a-t-elle été proposée pour la première fois ? Lorsque nous avons finalement réussi à en photographier un ?

Malheureusement, la célèbre réfutation de Johnson échoue. Elle a toutefois été classée parmi les sophismes logiques bien connus comme "l'appel à la pierre" ou "argumentum ad lapidem" - bravo Samuel Johnson !

Honnêteté intellectuelle

Les sophismes sont des erreurs de raisonnement que nous commettons souvent parce qu'elles semblent solides, qu'elles font appel à notre bon sens. Notre cerveau est naturellement attiré par certains modes de pensée irrationnels. Les exemples les plus fréquents sont : le sophisme ad hominem, le sophisme de la bande ou l'appel à l'autorité - autant d'exemples de la manière dont la sphère sociale affecte notre capacité à raisonner efficacement.

Donner un coup de pied dans un rocher ne va pas à l'encontre de l'idée que la perception et l'existence sont liées d'une manière ou d'une autre, puisque c'est mon expérience du rocher qui détermine sa réalité apparente. La faiblesse de Johnson ne signifie pas pour autant qu'il a tort, mais simplement que la différence entre quelque chose qui n'existe pas et quelque chose qui ne peut pas être détecté est encore floue.

Kastrup est également coupable d'un mauvais raisonnement ou d'une légère malhonnêteté dans ses arguments contre le matérialisme. Par exemple, il sélectionne les questions scientifiques qui soutiennent son argumentation tout en négligeant celles qui la remettent en cause. Il utilise par exemple une interprétation populaire du "principe de l'observateur" en physique quantique, tout en ignorant le modèle consensuel sur le cerveau et la perception.

Ce que le rocher met en évidence, c'est le fait qu'il ne peut être ignoré - ou que les rochers sont ignorés à vos risques et périls. Nous devons faire face à ce que nous voyons. L'exploration de mystères cachés sur la base d'une simple spéculation ou d'une philosophie de salon peut souvent être intéressante et parfois même utile, mais elle est circulaire et incomplète. Les idées prennent vie lorsqu'elles sont confrontées au monde. Produisent-elles des prédictions exactes ? Conduisent-elles au conflit ou à la transformation ?

Il se peut que des théières non encore détectées soient en orbite autour d'une planète extraterrestre. Certaines de ces théières pourraient même contenir de minuscules dragons cracheurs de feu ou les réponses à tous les mystères de la vie, ce qui serait fantastique.

La découverte de ces théières particulières ajouterait certainement à la somme des connaissances humaines. Donc, si vous pouvez imaginer, sans quitter votre fauteuil, pourquoi elles pourraient exister et où elles se trouvent, nous voulons le savoir. Mais tant que nous ne les aurons pas trouvées, il serait injustifié de vivre notre vie en fonction de ce que veulent les dragons de la théière.

Les idéalistes purs et durs imaginent que le fondement créatif de l'univers, qui n'a pas encore été détecté, est comme nous. Notre expérience du monde est un état mental, et c'est donc tout ce qu'il y a dans l'existence. Mais pourquoi ? Pourquoi mes limites seraient-elles celles de l'univers ? Le fait que mon expérience d'un arbre soit manifestement subjective, limitée et probablement incorrecte ne prouve en rien que les arbres n'existent pas. Ou qu'aucun phénomène ressemblant à un arbre ne peut exister en mon absence.

Difficile ou complexe

L'idée que l'esprit est en quelque sorte à la base de tout est redevenue populaire grâce au "problème difficile de la conscience". Ce problème a été popularisé par le philosophe David Chalmers. Il s'agit de savoir s'il est difficile pour nous d'accepter que l'esprit puisse naître de la matière.

Nous pouvons plus ou moins comprendre l'idée que les pierres et les chaises sont des choses qui apparaissent dans notre conscience - en d'autres termes, que la matière est quelque chose dont nous faisons l'expérience. Mais l'idée que des objets puissent être assemblés de manière à produire des pensées et des sentiments nous semble trop bizarre.

Pourquoi les atomes, les molécules et les cellules disposés sous forme de matière cérébrale produiraient-ils soudainement des espoirs et des rêves ?

Bien entendu, Chalmers est féru d'idéalisme : si tout est fait de conscience, ou si l'esprit est en quelque sorte fondamental, le problème difficile disparaît.

Soudain, le panpsychisme ne semble plus aussi fou - surtout si nous l'appelons : Théorie de l'information intégrée (TII).

La conscience peut être considérée comme un spectre - nous sommes capables d'identifier des degrés de conscience, par exemple une personne faisant une sieste est moins alerte qu'une personne jouant au badminton. L'IIT s'inspire de ce principe et affirme qu'une pierre est également consciente.

Les roches sont conscientes parce que le fait qu'elles réagissent à leur environnement - par exemple, elles tombent sur le sol lorsqu'on les laisse tomber, elles s'érodent avec le temps - signifie qu'elles "traitent de l'information". Selon l'IIT, la capacité d'une pierre à "traiter des données" de cette manière est une indication d'un minuscule degré de "conscience" - une sorte de proto-conscience.

L'avenir nous dira si l'IIT peut réellement devenir une théorie scientifique à part entière, ou s'il se contente de jouer avec notre vision du monde à l'aide de jeux de mots astucieux. Si l'IIT pouvait expliquer en quoi une feuille inconsciente soufflant dans le vent diffère d'une feuille consciente, ce serait un bon début.

Le "problème difficile" est peut-être plus une question philosophique que scientifique. De nombreux neurologues du domaine ne s'en préoccupent pas particulièrement. Le neuroscientifique Anil Seth, par exemple, se préoccupe davantage de ce qu'il appelle le "vrai problème".

Pour le Dr Seth, notre résistance à considérer l'esprit comme une simple propriété émergente de la matière est similaire aux débats que nous avions auparavant sur la vie. La vie est-elle une substance magique indépendante et flottante qui pénètre dans le corps, le transformant ainsi de matière innée en être vivant ? Ou bien la biologie est-elle un phénomène qui émerge automatiquement de certaines interactions physiques et chimiques ?

Tout comme nous avions du mal avec l'idée que la vie pouvait naître de la non-vie (abiogenèse), nous luttons aujourd'hui avec l'idée que l'esprit peut naître de la matière.

Pendant ce temps, Anil Seth et ses collègues se consacrent à l'étude du mesurable plutôt qu'à la réflexion métaphysique. Jetons un coup d'œil rapide à ce que son livre "Being you" a à dire sur le sujet :

Être vous

Le message principal du livre est que nous ne percevons pas les choses telles qu'elles sont. Nous sommes ce que le Dr Seth appelle des "machines à prédire", estimant et hallucinant (selon ses termes) notre monde et notre personne. Ces images de la réalité, ou notre expérience de ce qui se passe, sont produites par le cerveau sur la base de la mémoire et des données qu'il reçoit des sens.

On a l'impression que le monde est un ensemble d'objets et que nos sens sont comme des fenêtres transparentes sur ce monde.

Nous avons l'impression de percevoir directement le monde à travers ces fenêtres.

Nous pensons naïvement que nous sommes des organismes détecteurs de vérité. Par exemple, lorsque nous interagissons avec une tasse de café, il semble que cette expérience sujet/objet soit un résultat inévitable et inhérent aux circonstances. Il y a une tasse de café sur la table et moi, l'observateur, qui regarde la tasse. Ce qui est perçu semble découler inévitablement, nécessairement, de la relation entre les entités réelles présentes : moi "ici" et la tasse "là-bas".

Cela peut être vrai dans le sens où je n'ai pas le choix : il est inévitable que mon activité neuronale particulière produise une expérience particulière. D'un autre côté, il est douteux que tous les cerveaux humains produisent exactement la même expérience, et si nous considérons l'expérience des araignées... tous les paris sont ouverts.

C'est donc notre cerveau, et non les objets supposés perçus, qui est la clé. C'est la matière grise dans ma tête qui est à l'origine de toute cette aventure avec la tasse de café.

Mon cerveau produit le sentiment d'être moi-même et d'interagir avec tous les autres entités qu'il a créés.

Il décide de ce à quoi ressemble mon monde en devinant - ou si cela semble trop désinvolte : en se basant sur les probabilités. Il fait la meilleure prédiction possible sur ce qui se passe - et donc sur ce que je devrais voir - en se basant sur toutes les informations qu'il reçoit. Cela inclut les données qu'il reçoit de tous les sens, c'est-à-dire des oreilles, des yeux, de la peau, etc. ainsi que de la mémoire.

Les données sont comparées à des événements similaires du passé pour produire une image neuronale - Seth utilise le terme "fantaisie neuronale" car l'expérience n'est pas exclusivement visuelle. Et cette image, nous la prenons pour une relation directe avec le monde, ce que nous prenons pour une fenêtre transparente sur la vérité.

Cette image est constamment affinée. Le cerveau réajuste sans cesse ce que nous voyons à mesure que de nouvelles données arrivent, généralement en préservant la continuité de notre réalité. Par exemple, si nous sortons une feuille de papier blanc à l'extérieur, elle continuera à avoir la même apparence que lorsque nous l'avons vue à l'intérieur. Bien que les informations fournies par nos yeux aient changé - l'éclairage a changé, nos yeux se sont adaptés à la lumière changeante - l'apparence du papier reste la même pour nous.

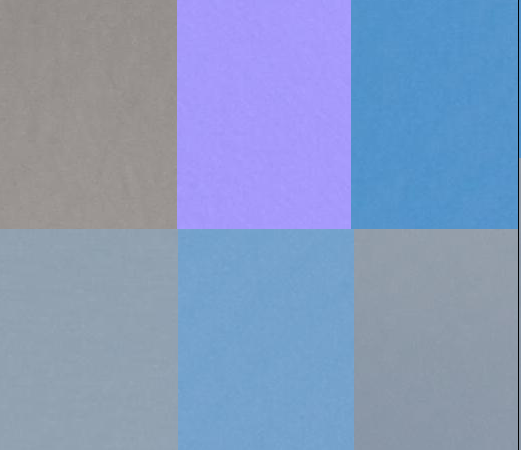

Regardez la figure ci-dessous. Il s'agit d'une mosaïque de 6 photos que j'ai prises d'une feuille blanche à différents endroits, en commençant par mon bureau en haut à gauche, en passant par mon balcon ombragé, jusqu'à un endroit ensoleillé dans le jardin en bas à droite.

Si nous pouvons faire confiance à mon appareil photo (ou si vous réalisez l'expérience vous-même), nous devons admettre que la teinte ou la couleur de la feuille de papier est modifiée au fur et à mesure qu'elle se déplace dans son environnement. L'apparence constante de blancheur que j'obtenais ne peut donc pas être due à la qualité de l'objet "là-bas". L'objet me paraissait toujours blanc, mais ma perception de la blancheur n'était pas le reflet exact d'un phénomène indépendant.

Lorsque nous nous accordons sur une vérité objective concernant le monde - comme les qualités d'une feuille de papier - nous partons simplement du principe que nous partageons la même appréciation. Ce qui est probablement correct, étant donné que nous partageons tous des environnements et des synapses très similaires.

La rougeur ou la blancheur est une expérience phénoménologique subjective de la façon dont la lumière se reflète sur les objets. La couleur est la façon dont nous percevons la lumière lorsqu'elle interagit avec son environnement. C'est ce que signifie l'expérience : comment nous nous sentons dans le monde - et non pas comment le monde est. La couleur, la forme, la solidité, la texture, la température, etc. sont des projections neurologiques.

Ainsi, ce que nous appelons "réalité objective" peut être défini comme une "hallucination partagée", c'est-à-dire un consensus sur ce que nous percevons.

Il y a une autre implication importante dans ce processus où mon cerveau affine constamment sa projection prédictive du monde sur la base des données sensorielles et de la mémoire. C'est que nous ne découvrons pratiquement jamais rien de complètement nouveau ou d'original.

Le fait que les images neurologiques produites soient des prédictions basées sur des expériences antérieures signifie inévitablement que je reconnais toujours, au mieux, une sorte de réinterprétation du passé.

Prenons l'exemple de la première fois que j'ai vu un gorille ou que j'ai découvert le concept de gorille. Même ce premier gorille n'était pas totalement nouveau pour moi. Je l'ai immédiatement reconnu comme un exemple légèrement différent de quelque chose de familier : un énorme singe à fourrure peut-être, un type dans un costume de Yéti géant, un monstre des royaumes démoniaques venu pour avaler mon âme, etc.

Quoi qu'il en soit, le fait est que mon expérience de la réalité dépend en grande partie de la familiarité.

La familiarité favorise la plausibilité

Les neurologues nous disent que notre cerveau est assis dans une boîte sombre et sécurisée (le crâne) et qu'il doit déduire des causes cachées des données qu'il reçoit des sens. Il fait des prédictions sur ces données sensorielles, reçues sous forme d'impulsions électriques, et crée une image sensuelle qui semble absolument authentique et irréfutable.

Les neurosciences ont élaboré ce modèle de perception en examinant ce qui est observable et mesurable. Nous demandons aux gens ce qu'ils voient, nous jouons avec différentes longueurs d'onde, nous mesurons l'activité électrique dans le cerveau, etc... Et nous construisons un modèle qui correspond le mieux aux données.

C'est ce qu'Anil Seth appelle le "vrai problème" de la conscience : produire les modèles les plus précis possibles de ce qui se passe réellement, en fonction des preuves disponibles.

Le "problème difficile" est l'expression de l'étrangeté du modèle consensuel de la conscience. Bizarre parce qu'il contredit des sentiments et des croyances familiers.

Les choses courantes semblent normales et nous n'avons donc pas tendance à remettre en question nos hypothèses quotidiennes. Je me sens tout à fait en sécurité dans ma compréhension des chaises et des pierres. Mes croyances religieuses me paraissent tout à fait légitimes et raisonnables, alors que les vôtres me semblent tout à fait scandaleuses et stupides.

L'idée que des processus électrochimiques puissent générer des expériences conscientes contredit ma vision du monde, elle semble déraisonnable, difficile à croire ou à comprendre. J'exprime donc ma difficulté : pourquoi l'activité de mon système nerveux central produirait-elle des espoirs et des rêves ? Comment cela fonctionne-t-il exactement ?

Des questions difficiles qui pourraient un jour susciter des réponses utiles. Mais cela me rappelle que je ne sais pas vraiment pourquoi les pierres tombent sur le sol, ni comment ma chaise supporte mon poids.

Les pierres tombent parce que la masse de la Terre a créé un puits de gravité dans l'espace-temps. Je peux répéter l'explication scientifique que je connais, mais je ne sais pas vraiment comment ou pourquoi la masse crée un puits dans l'espace-temps. La chaise me tient debout grâce à la danse des électrons, apparemment. Le fait est que ces énigmes quotidiennes ne me troublent pas. Je suis tout à fait satisfait de vivre avec ces mystères banals.

4 réponses à "Consciousness

-

UteS

Comment naissent les espoirs et les rêves ?

Je ne connais pas la réponse, mais je trouve les phénomènes eux-mêmes intéressants. Il est fascinant que la lumière soit présente dans les rêves, par exemple, ou que les souvenirs puissent se dérouler comme des films internes alors que l'environnement extérieur réel s'estompe.

Ou la couleur réelle de la feuille de papier dans différentes conditions d'éclairage :

On pourrait décrire la couleur de la mer comme étant bleue - si vous restez longtemps au bord de la mer et que vous avez le temps de la regarder, selon le temps, elle peut être noire comme du verre volcanique brisé, d'un turquoise profond, comme si elle était recouverte d'un film plastique, complètement plate et argentée ou effroyablement agitée d'un bleu-gris terne et de bien d'autres manifestations.

Il semble que nous utilisions "feuille blanche" et "mer bleue" dans nos pensées quotidiennes comme un cliché bidimensionnel, comme une "chose en soi" séparée de son contexte. En conséquence, ils perdent leur profondeur et leur vitalité. Elle devient une image statique que nous traitons.-

macdougdoug

Bonjour UteS, ravi de vous voir ici ! Ce que vous dites me fait penser au langage, et au fait que notre expérience du monde fondée sur des images statiques ou des clichés était probablement nécessaire à l'évolution du langage. Les mots sont des symboles pour les images fixes ou les concepts, c'est-à-dire les choses qui existent dans notre conscience.

-

-

UteS

Bonjour Macdougdoug - joli blog qui soulève des questions intéressantes. J'aurais dû commencer par là 🙂

Ces images et concepts figés semblent également jouer un rôle important :

"Les sophismes logiques sont des erreurs de raisonnement que nous commettons souvent parce qu'elles semblent solides, qu'elles font appel à notre bon sens. Notre cerveau est naturellement attiré par certains modes de pensée irrationnels. Les exemples les plus fréquents sont : le sophisme ad hominem, le sophisme de la bande ou l'appel à l'autorité - qui sont tous des exemples de la manière dont la sphère sociale affecte notre capacité à raisonner efficacement".Il me semble que les sophismes mentionnés sont un refus de s'engager sur une question. Une déclaration va à l'encontre de votre propre opinion et vous ne voulez pas qu'elle soit remise en question. Comme vous n'avez même pas envie d'écouter une opinion différente, vous préférez disqualifier la personne, vous référer à l'opinion dominante ou argumenter sur quelque chose qui n'a même pas été dit (argument de l'homme de paille) ou encore rabrouer l'autre personne d'emblée, en voulant bannir l'autre point de vue ou l'autre approche.

Vous ne voulez même pas entendre ce qui se dit. Une énorme défense qui ne peut être expliquée rationnellement.-

macdougdoug

Oui, cela semble être le principal problème de notre relation avec le monde. Le fait que ce que je dis ou fais semble si important. À tel point que je m'accroche à la stupidité ou que je me bats avec mon voisin lorsqu'on me met au défi. L'autorité du moi inclut la confusion et le conflit que nous voyons dans le monde.

-

Laisser un commentaire