Le pouvoir des mèmes

L'autre jour, j'ai eu une conversation intellectuelle avec un ami - sur la moralité ou le sens de la vie, ou quelque chose comme ça (j'ai oublié) - et c'était le bordel. Bonjour le dialogue de sourds - nous parlions la même langue, mais semblions vivre dans des réalités différentes.

En essayant de trouver un terrain d’entente, un fait simple sur lequel nous pourrions au moins nous accorder - j'ai attrapé quelques amuse-gueules sur le comptoir. Pouvions-nous au moins convenir que je tenais des olives ? Eh bien… non.

Notre confusion semblait porter sur deux points : le mot vraiet la mécanique quantique.

J'avais demandé : "est-ce que c'est vrai qu'il y a des olives dans ce bol ?".

La vérité est malheureusement un concept sujet a controverse, et rien que l’emploi du mot a provoqué chez mon ami une sorte de résistance mentale.

L'incertitude entourant les (prétendues) olives était encore exagérée par son intérêt pour la physique quantique. D'une certaine manière, l'existence d'une chose peut être remise en question par rapport à ce que nous savons de sa structure subatomique.

L’argument, dans ses grandes lignes, était le suivant : 1) La matière est constituées d'un espace essentiellement vide. 2) Ce que nous considérons comme des particules dans cet espace ne sont en fait que des champs de probabilité énergétiques. Par conséquent, les olives n'existent pas.

La conversation s'est arrêtée là - nous avons peut-être mentionné un chat qui était à la fois vivant et mort - mais c'est à peu près tout. Nous avons bu un peu de vin pour nous calmer, nous avons ignoré ce qui se trouvait ou non dans le petit bol, et nous sommes partis chacun de notre côté (et nous avons évité le sujet des olives depuis lors).

Nul besoin d'être un philosophe de salon pour avoir remarqué l'embrouille actuel autour de nos "vérités" subjectives. L'époque actuelle a été baptisée "post-vérité". Les effets négatifs du tribalisme comme fondement de la vérité font la une des journaux.

En règle générale, nous croyons et défendons ce que disent les personnes en qui nous avons confiance. En tant qu'Européen éduqué de la génération X, j'essaie de m'aligner sur le consensus scientifique. Une personne élevée dans un environnement plus rural et religieux peut être influencée par son prêtre. Une personne née à l'ère de l'internet peut se former uniquement grâces aux ritournelles idéologiques des réseaux sociaux.

Et le plus souvent, nous pouvons être quelqu'un qui n'entre dans aucune de ces catégories. C'est pourquoi, dans la plupart des cas, notre vision du monde est faite de contradictions et de confusion.

Quoi qu'il en soit, les visions du monde sont automatiquement façonnées par la culture à laquelle nous nous identifions. Et si vous et moi nous identifions à des pôles culturels opposés, nous sommes naturellement en conflit. Nous sommes émotionnellement et idéologiquement opposés. En désaccord, incapables d'écouter, et encore moins de communiquer.

Nos idées nous sont précieuses et nous nous sentons obligés de les défendre, de la même manière que nous nous battons pour protéger notre maison ou notre famille. Nous sommes contrariés lorsque nos valeurs sont remises en question : notre rythme cardiaque s'accélère, l'adrénaline entre dans le système.

C'est comme si notre survie, ou notre bien-être, exigeait que les croyances soient protégées, qu'elles soient gravées dans la pierre, qu'elles ne changent jamais.

Nous avons étudié certains travaux universitaires au cours des derniers chapitres à propos de ces phénomènes. J'ai cité sans vergogne une brochette de psychologues, d'anthropologues et de neurologues qui ont décrit les forces en jeu dans la nature et le comportement humains. Le pouvoir des mèmes est profondément ancré. Nous sommes automatiquement amenés à réagir à l'autorité de nos récits intérieurs.

Contenu et processus

Mais assez de science. Changeons de cap avec la question suivante : et alors ? Qu'est-ce que toutes ces données signifient pour moi ? La plupart des gens ne travaillent pas dans l'un de ces domaines - nous ne sommes pas des universitaires - personne ne nous demande d'écrire un article scientifique.

C'est peut être fascinant (au moins pour les personnes étranges qui aiment ce genre de choses), mais en quoi tout cela est-il important ? En quoi cela change-t-il ma vie ? Suis-je différent ? Ou bien tout ce savoir-faire n'a-t-il fait qu'ajouter une complexité supplémentaire à ma vision déjà confuse du monde ? S'agit-il simplement d'alimenter un dogme ? Suis-je accro à l'information ?

Il est évident que nous ne pouvons pas nous empêcher d'être préoccupés par notre situation. C'est essentiellement ce qu'est un problème : une situation embêtante qui nous préoccupe et que nous voulons résoudre.

Un problème peut être abordé de deux manières : soit en traitant les symptômes, soit en comprenant ce qui se passe réellement.

On pourrait même affirmer que la compréhension d'un problème et sa résolution sont à peu près la même chose. C'est évident dans les problèmes de mathématiques par exemple. Prenons la question suivante : quelle est la somme de 1+1 ?

Si je comprends ce qu'est une somme, le sens du chiffre 1 et ce que signifie +, le problème est pratiquement résolu.

Cela devient bien sûr plus délicat si je fait partie du puzzle, ce qui est malheureusement le cas dans ma vie de tous les jours. Il est évident que je suis toujours présent, impliqué et probablement au cœur des difficultés qui me concernent au quotidien. Mais étrangement, mes émotions et mes opinions ne sont pas considérées comme faisant partie de l'équation. Pourtant, elles façonnent ce que nous voyons, notre interprétation, et dictent notre réaction dans n'importe quelle situation.

Si quelqu'un m'offre du bacon, il n'y a pas de mal sauf si je suis musulman, végétalien ou au régime - ce qui compte, c'est qui je suis. Que le socialisme, la charia, la législation sur les armes à feu, etc. soient perçus comme positif ou de négatif dépend de la personne qui regarde. Les problèmes dépendent d'un point de vue.

Nous pouvons remarquer que d'autres personnes ont des relations inutilement conflictuelles avec la réalité. Mais notre propre relation mentale et émotionnelle à une situation est généralement considérée comme appropriée - si tant est qu'elle soit prise en compte. Mes propres opinions ressemblent plus à des faits qu'à des préjugés. Mes sentiments me donnent l'impression d'être guidés par des données concrètes. J'ai l'impression que la situation dicte en quelque sorte ma reaction.

Plutôt que de conditionner ce que nous voyons, plutôt que d'affecter notre comportement, notre expérience subjective n'est pas considérée comme pertinente - comme faisant partie de ce qui se passe. Plutôt qu'une variable de l'équation ou un élément essentiel du problème, notre propre point de vue nous apparaît comme un cadre fondamental de la façon dont les choses sont, une réponse rationnelle à la vérité.

Les problèmes sont toujours présentés comme quelque chose qui m'arrive de l'extérieur, plutôt que comme quelque chose dont je fais partie. Bien que je fasse partie intégrante du mélodrame qui se joue, le dilemme et moi sommes en quelque sorte distincts.

Je peux me sentir victime, je peux vouloir changer la situation, reprendre le contrôle - mais mon attitude et mon opinion ne semblent pas faire partie du problème, elles sont considérées comme une réaction au problème.

Bien sûr, les concepts sont utiles. La capacité d'identifier la victime dans une relation abusive aide tout le monde à comprendre les enjeux d'un procès, par exemple. Ou encore, elle permet d'examiner la dynamique du pouvoir lorsqu'on est attaqué par un ours ou lorsqu'on se voit proposer une arnaque de type pyramidal.

En ce qui concerne nos préoccupations banales, nos angoisses quotidiennes - les dangers potentiels, les enfants affamés à la télé, les factures à payer, le bonheur de nos proches, etc. Nous voulons simplement savoir comment naviguer au mieux, nous voulons des solutions, nous voulons nous mettre en sécurité.

La connaissance est notre super pouvoir, notre façon particulière de faire face à la vie - les chauves-souris ont un sonar, une pieuvre a des bras intelligents, l'homo sapiens a la connaissance. La connaissance nous rassure, elle nous aide à nous sentir en sécurité. Elle nous donne les moyens de progresser.

Dans les chapitres précédents, nous avons étudié la manière dont les connaissances sont acquises par le biais de la culture. Mes idées sur le monde et sur la manière de s'y comporter proviennent de ma communauté - nous imitons ce que font les autres et adoptons ce qu'ils disent. Il se peut que je porte une cravate et cherche un emploi, et que vous soyez à moitié nu à la poursuite d'une antilope, ou à cheval avec un faucon à la main, parce que c'est ce que font tous nos congénères.

Ma psychologie et mon comportement sont conditionnés par ma biologie et la culture ou la société dans laquelle je grandis. J'agirai en accord ou en résistance avec ce qui a été identifié comme normal. Ma réalité a été encadrée par les expériences que j'ai vécues.

La croyance restreint la réalité

Si nous avons été attentifs, nous avons peut-être remarqué que notre relation automatique avec la réalité est plutôt aléatoire. Nos réactions spontanées peuvent tout aussi bien se solder par des larmes que par de la joie ou du réconfort, qu'il s'agisse de nos propres interactions quotidiennes ou de l'histoire de l'essor et de l'effondrement des civilisations en général. Les histoires que nous avons adoptées ont autant de chances d'être une aide qu'un obstacle - seul le temps nous le dira. La force des circonstances (c'est-à-dire la sélection naturelle) désignera les gagnants et les perdants.

Tout au long de l'histoire, les hommes et leurs tribus ont agi sur le monde, guidés par des visions subjectives du monde. Nous avons déclaré la guerre, pratiqué des mutilations rituelles, célébré des anniversaires, coopéré et distribué des richesses selon divers récits traditionnels. Nous avons survécu et parfois même prospéré dans le cadre de diverses normes sociétales. Mais, un jour ou l'autre, même la plus chanceuse de ces sociétés se heurte à un défi qui n'est pas suffisamment pris en compte par ses diktats culturels.

Parfois, le danger est extérieur : une longue période de sécheresse ou l'apparition d'une horde de Mongols assoiffés de sang. Parfois, nous provoquons notre propre chute : trop de cannibalisme, de consanguinité ou de mauvaise gestion de l'environnement.

Quoi qu'il en soit, si nos réactions manquent totalement leur but ou aggravent la situation, nous avons tendance à rester confus et limités par nos œillères culturelles. Ma vision du monde tend à restreindre mon champ d'action et de compréhension.

Si j'estime que fumer des cigarettes, utiliser des huiles essentielles ou faire de longues promenades sont essentiels à mon bien-être, j'agirai probablement en conséquence.

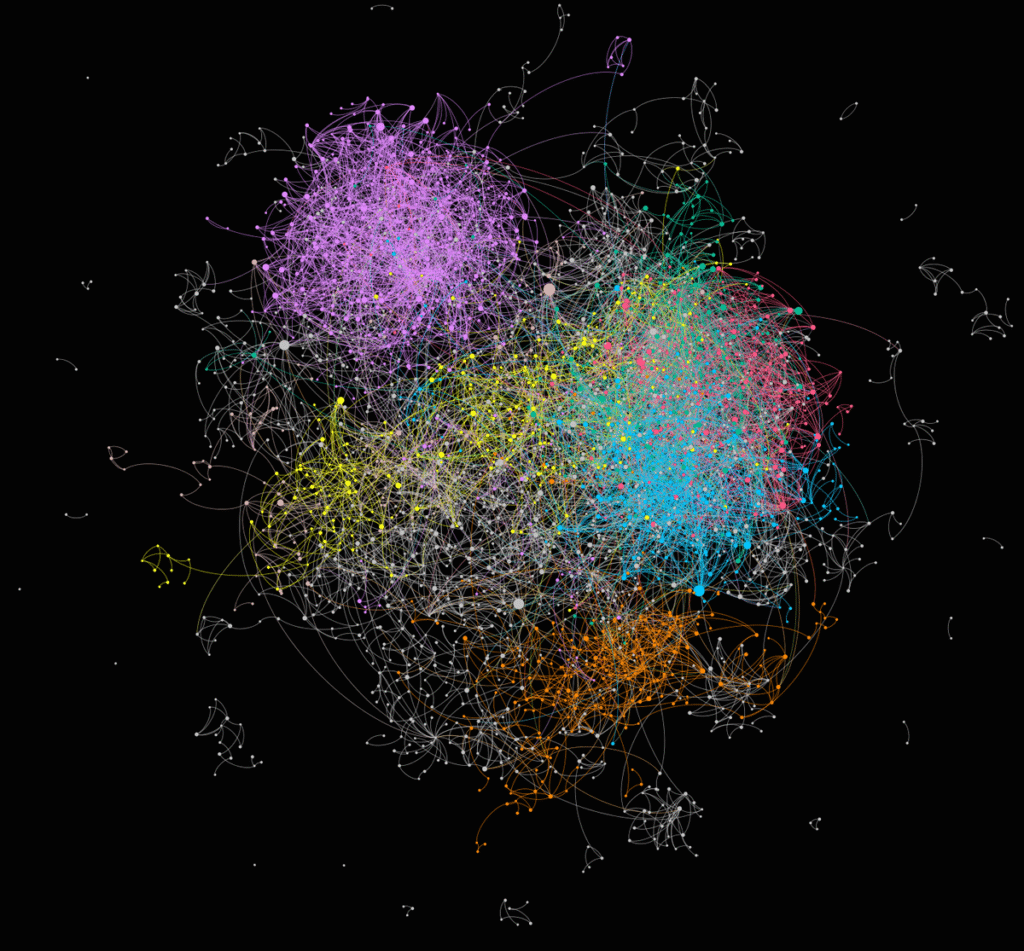

Les effets réels de mes croyances et des comportements qui y sont associés me resteront très probablement cachés. J'aurai bien sûr des opinions sur mes opinions. J'aurai une expérience subjective de ce qui se passe, mais les effets de mes actions échapperont largement à ma perception (notamment parce que ce que nous voyons est limité par la biologie et par nos connaissances, et parce que les conséquences peuvent se multiplier le long d'un réseau infini d'interactions).

Nous sommes probablement d'accord pour dire que la cause et l'effet (ou les événements corollaires) sont une évidence - il y aura des conséquences. Les actions découlant des récits que j'ai adoptés m'affecteront, ainsi que mes relations. Certaines peuvent être largement insignifiantes, d'autres, espérons-le, bénéfiques, et d'autres encore causeront des préjudices...

Cela signifie qu'au moins certaines croyances sont une cause de préjudice. Un mal que nous créons automatiquement, par habitude, souvent sans le vouloir. Et s'il y a des gens que nous aimons autour de nous, ils seront également affectés. Nous nous traumatisons mécaniquement, nous et nos proches, et par extension, le monde dans son ensemble.

L'histoire récente regorge d'exemples d'abus quotidiens que nous nous sommes joyeusement infligés à nous-mêmes. Nous pouvons citer le tabagisme ou la violence à l'encontre des d'enfants comme étant nuisibles parce que les opinions sur ces pratiques se sont inversées - les normes sociétales actuelles concernant ces questions contredisent les points de vue traditionnels. Autrefois, fumer était cool, et la violence envers les enfants était considérée comme bénéfique.

Les récits que nous avons intériorisés comme étant vrais dictent notre comportement. Nous agissons en fonction de ce qui nous semble juste.

Actuellement (en 2025), cela pourrait signifier faire des efforts pour protéger nos enfants contre les vaccins, ou au contraire chercher à faire vacciner nos enfants. Si je suis chef d'État, cela pourrait signifier déclarer la guerre à l'Ukraine.

Je m'efforcerai de faire tout ce que mon récit interne considère comme nécessaire. Ce qui semble vrai a une immense autorité, parce qu'il semble si essentiel et correct.

Des Néandertaliens avec des armes nucléaires

Cela ressemble beaucoup au point crucial de notre enquête : les dommages incessants que nous nous infligeons et que nous infligeons aux autres peuvent ne pas être nécessaires ou raisonnables.

S'il est vrai que notre comportement découle automatiquement de ce que nous sommes, tout le monde a intérêt à se faire une idée plus claire de ce qui nous motive.

Si je suis préoccupé par toutes les souffrances du monde, je veux en comprendre l'origine.

À certains égards, l'humanité a parcouru un long chemin. Grâce à la science, à la technologie et au commerce, un grand nombre de personnes ont acquis une richesse et un pouvoir immenses. Mais à d'autres égards, nous ne semblons pas avoir changé du tout. Les processus psychologiques primitifs qui animent chacun d'entre nous sont les mêmes que par le passé. Que je sois un milliardaire des temps modernes ou un gardien de chèvres préhistorique, mes angoisses, mes valeurs et mes désirs dictent toujours mes actions. Tout ce qui semble avoir quelque peu changé, ce sont les objets dont j'ai envie.

Nos visions du monde sont encore largement formées de la même manière. Nous pourrions dire que la vision de la réalité du chevrier était façonnée par des histoires traditionnelles ou des mythes, et que la nôtre est conditionnée par des récits culturels modernes - mais bien sûr, ce ne sont que des mots différents pour désigner la même chose. Leurs mythes peuvent inclure des personnages comme Thor, Osiris et le dôme du firmament, et les nôtres peuvent contenir des éléments plus raisonnables comme l'IA, le capitalisme et Jésus, mais il s'agit toujours fondamentalement de récits. Et notre relation aux récits n'a pas changé. Les histoires que nous considérons comme vraies ont toujours une immense autorité sur nous.

Malgré les avantages offerts par le monde moderne, nous ne semblons pas avoir changé sur le plan psychologique. Malgré notre immense pouvoir, nous sommes émotionnellement encore à l'âge de pierre.

Et ces mêmes émotions continuent de conduire mécaniquement le comportement, ce qui inclut notre comportement violent et inutilement destructeur.

Un comportement violent qui est le fruit des meilleures intentions. Ma colère est toujours justifiée, mes désirs sont toujours considérés comme des besoins, mon intelligence est toujours injustement remise en question par des imbéciles. Avec les résultats malheureux que l'on constate et qui touchent tout le monde, de nos enfants à la société dans son ensemble, en passant par des pays entiers en état de siège, le réchauffement de la planète et l'extinction massive actuelle.

La question de savoir s'il est possible de voir ce processus de préjudice en action semble essentielle. Si nous nous en soucions. Si nous nous soucions du mal que nous imposons au monde.

Les raisons pour lesquelles nous causons du tort sont-elles claires ?

Nous avons examiné comment nos comportements découlent inévitablement de ce que nous sommes, de notre culture, de notre psychologie et de notre biologie, telles qu'elles ont été formées au fil de milliers de générations. Les comportements persistent parce qu'ils sont efficaces : nous sommes allés de l'avant et nous nous sommes multipliés...

Les habitudes culturelles qui causent trop de dégâts auront des conséquences - elles finiront par s'ajouter à la balance et joueront un rôle dans tout effondrement potentiel qui pourrait se produire. Dans un environnement en constante évolution, même des habitudes autrefois bénéfiques peuvent devenir préjudiciables. Notre dépendance au sucre dans un monde d'abondance est un exemple souvent cité.

Les mécanismes de survie qui font plus de mal que de bien ne sont plus des mécanismes de survie. Ce qui était un comportement essentiel devient une menace existentielle.

Quelle est la plus grande menace qui pèse sur l'humanité ? Parmi les périls hypothétiques, citons les astéroïdes géants, les super-volcans ou les invasions extraterrestres. Quelles que soient les chances que ces cataclysmes se produisent, nous aurons peut-être un jour les moyens de faire face à certains de ces scénarios. Des astronomes, des ingénieurs, des géologues, etc. travaillent actuellement sur ces questions.

Plus à propos, la plupart des scénarios menaçant l'humanité impliquent des humains.

ie. Guerre nucléaire, changement climatique, IA maléfique, pandémies issues de la bio-ingénierie, effondrement de la biosphère...

En réalité, alors que nous sommes confortablement assis ici, la sixième extinction planétaire est déjà en cours. Une extinction causée par l'activité humaine. Ce n'est même pas la première fois que l'un des habitants de la Terre provoque la mort de toute la planète à grande échelle. La Grand événement d'oxydationqui a apparemment détruit environ 80% de tous les êtres vivants, a été causée par des cyanobactéries.

Quoi qu'il en soit, la seule crise existentielle qui se produit en ce moment est provoquée par nous mêmes.

Je pense que nous sommes également d'accord pour dire que les deux dernières fois que nous avons évité le pire, l'homme était dans les parages : le trou dans la couche d'ozone (saluons James Lovelock !) et les doigts qui hésitaient sur le bouton de lancement nucléaire pendant la guerre froide.

L'extinction catastrophique est généralement considérée comme une mauvaise chose, en particulier par les personnes qui la subissent.

La différence entre les cyanobactéries ou les astéroïdes géants et les humains est que nous semblons avoir au moins une petite idée de ce que nous faisons. Nous semblons être au moins quelque peu conscients des implications plus larges de nos actions.

Prenons par exemple les dix commandements de la Bible, qui comprennent des règles telles que "Tu ne tueras pas... tu ne voleras pas et tu ne porteras pas de faux témoignage". Ces commandements ont été rédigés il y a plus de 3 500 ans, ce qui prouve que le comportement humain était déjà un mal reconnu à l'âge du bronze.

Nous aggravons souvent notre situation, ce qui est étrange étant donné que nous sommes constamment motivés pour améliorer notre vie. Bien que nous voulions le meilleur pour nous-mêmes, nos préoccupations nous poussent souvent à agir de manière nuisible. À tel point que nous devons élaborer des lois et nous efforcer de les faire respecter pour que la société puisse fonctionner.

C'est dans cette direction que j'aimerais maintenant m'orienter, en examinant quelques tentatives pour répondre à cette impulsion inhérente à la violence inutile ou malavisée.