Idéalisme et matérialisme

Commençons par quelques citations qui devraient maintenant vous sembler familières. La première est d'Albert Einstein : "L'espace et le temps sont des modes par lesquels nous pensons, et non des conditions dans lesquelles nous vivons.

La seconde vient d'Ikhwan al-Sufa, un philosophe arabe qui a vécu près de 3 000 ans avant Einstein : "L'espace est une forme abstraite de la matière et n'existe que dans la conscience.

Pour information, ces citations ne proviennent pas de la page Facebook de ma grand-mère, mais d'un site web de l'université de Stanford. site web consacré à Einstein et à la gravité.

L'Université de Stanford nous aidera également à définir certains concepts philosophiques - grâce à leur excellente Encyclopédie de la philosophie - - car nous allons nous plonger rapidement dans l'"idéalisme".

Donald Hoffman est un idéaliste. Sa théorie de l'interface de la perception (PTI) postule que nous interagissons avec la réalité par l'intermédiaire de l'interface mentale de notre expérience, qui est fournie par notre cerveau. C'est à peu près la description de ce que l'on appelle : Idéalisme épistémologique. Défini par l'encyclopédie Stanford comme suit :

"Tout ce que nous pouvons connaître de la réalité nous est présenté par l'esprit".

Tout ce que nous vivons et connaissons est une projection mentale basée sur les données sensorielles et la mémoire. Espérons qu'après les quelques chapitres précédents, ce concept ne soit plus aussi flou. Mais ne vous inquiétez pas, nous sommes sur le point d'examiner à nouveau notre relation avec la réalité sous deux angles différents : la philosophie et la neurologie.

Alors, êtes-vous matérialiste ou idéaliste ? Quelle est votre position philosophique ?

Vivez-vous dans le monde réel des choses solides séparées par un espace vide ? Est-ce que vous et le monde êtes vraiment ce qu'ils semblent être ? Ou êtes-vous coincés dans une projection mentale floue ? Est-ce que vous et votre monde êtes le produit de votre propre imagination ?

De toute évidence, nous avons l'impression que le monde dont nous faisons l'expérience est réel - nous nous comportons comme des matérialistes (ou des réalistes, une vision du monde similaire). Mais attention, spoiler alert ! Bien que le matérialisme soit le modèle dominant de la réalité depuis environ un siècle, même les matérialistes doivent accepter l'"idéalisme épistémologique" et rejeter le "réalisme naïf".

La notion naïve selon laquelle nous percevons toujours la vie "là-bas" telle qu'elle est réellement ne tient pas. À cause des illusions visuelles, par exemple, ou parce que la réalité que nous voyons n'a rien à voir avec ce que nous dit la physique. Ou tout simplement parce que nous n'avons pas tous les mêmes expériences et que, si nous pouvons tous nous tromper, nous ne pouvons pas tous avoir raison - surtout lorsque ces expériences sont contradictoires.

Et si nous acceptons le modèle neurologique actuel de la conscience - nous y reviendrons dans un instant - nous devons accepter que l'expérience est mentale.

Si nous admettons que notre expérience d'un monde matériel est en fait un état mental, cela signifie-t-il que nous pouvons conclure que la réalité actuelle est fondamentalement quelque chose de mental ? Si mon expérience de la réalité se produit dans mon esprit, cela signifie-t-il nécessairement que l'univers est fait d'esprit, de conscience pure ?

Non, ce serait un saut énorme (illogique). Comme un poisson nageant dans la mer qui conclurait que l'univers entier doit être fait d'eau.

Néanmoins, j'ai l'impression que certaines personnes affirment que la réalité est fondamentalement une sorte d'esprit immatériel.

Ces personnes sont des idéalistes ontologiques ou métaphysiques. Ils épousent ce que l'on pourrait appeler l'idéalisme dur, par opposition à son cousin plus doux : l'idéalisme épistémologique.

Avant d'explorer le raisonnement qui sous-tend leur vision du monde, permettez-moi de planter une épingle là où se trouve le principal point de confusion :

Lorsque l'on dit : "la réalité est fondamentalement une construction mentale", tout dépend de ce que l'on entend par "réalité".

S'agit-il de "ce que nous voyons lorsque nous regardons le monde" ou d'une vérité fondamentale cachée sur le monde qui existe indépendamment de nous ? En examinant les arguments, nous devons garder cette dichotomie à l'esprit, afin de repérer tout appât soudain et tout changement entre ces deux concepts.

Insérer Dieu ici

Je suis peut-être en train d'empoisonner les eaux avant même d'y plonger, alors je m'en excuse, mais j'ai remarqué quelque chose d'autre chez les personnes qui s'identifient comme des idéalistes purs et durs. Ils sont biaisés. Ce qui ne veut pas dire que le réalisme l'emporte, car soyons réalistes : nous le sommes tous.

Nous sommes tous nés dans une culture particulière, et nombre d'entre nous, des deux côtés du débat entre réalisme et idéalisme, ont été baignés dans une certaine version de l'idéalisme platonicien. Il s'agit de l'idée que la matière est en quelque sorte inférieure à son essence. La matière est en quelque sorte corrompue, moins pure que son essence, qui est une sorte de "forme" immatérielle idéale, parfaite et intemporelle.

Nous pensons que notre "esprit" ou notre "âme" est ce que nous sommes vraiment. Que notre esprit est en quelque sorte supérieur, plus essentiel que notre incarnation matérielle.

Ainsi, lorsque les idéalistes défendent la primauté de la conscience sur la matière, ils défendent souvent un endoctrinement religieux. Lorsqu'ils parlent de la conscience comme du "fondement immatériel de l'existence", ils parlent en fait de Dieu.

Le père de Donald Hoffman était un prédicateur chrétien fondamentaliste, adepte de la création d'une nouvelle Terre. En somme, un littéraliste de la Bible. Même si Donald a réussi à voler de ses propres ailes et à devenir un scientifique respecté, il est né dans un monde où Dieu était toujours présent - à la maison, à l'école, à l'église. Aussi, lorsqu'il insiste sur le fait que la conscience est en quelque sorte plus fondamentale que son contenu - des contenus tels que l'espace-temps et les objets que nous percevons par exemple - sans rien pour étayer son affirmation, je me méfie. Je pense : présupposés !

Puisque je fais part de mes soupçons plutôt que d'exposer simplement les arguments, autant dire la vérité : je ne supporte pas Bernardo Kastrup ! Ou du moins, je ne supporte plus de l'écouter ou de le lire.

Bernardo m'est apparu comme l'éminent défenseur de l'idéalisme moderne, et je l'ai donc écouté. J'ai lu son livre Je l'ai parcouru à plusieurs reprises, en échouant la plupart du temps lamentablement à comprendre de quoi il parlait.

L'échec est douloureux, et c'est pourquoi je suis devenu quelque peu réticent à l'égard de M. Kastrup. Je me méfie de son intelligence, de ses déclarations mystérieuses qui restent mystérieuses même si j'essaie de les comprendre. Bien sûr, c'est peut-être entièrement de ma faute - ma difficulté à comprendre les mathématiques complexes ne signifie pas que la trigonométrie est un tas d'absurdités.

Quoi qu'il en soit, vous êtes prévenus. Malgré tout, je vais quand même vous présenter le peu que j'ai réussi à tirer du livre de Kastrup.

L'idée du monde

Bernardo commence bien en formulant le débat entre matérialistes et idéalistes en deux questions simples :

L'esprit et la matière sont-ils des opposés polaires ? Ou bien l'un découle-t-il de l'autre ?

Si nous n'avons jamais vraiment exploré ce sujet, ces questions peuvent sembler stupides. L'esprit et la matière sont-ils opposés ? Nous pourrions dire "bien sûr que oui ! - c'est ce que nous voulons dire lorsque nous prononçons ces mots". Les pensées et les idées ne sont pas du tout comme des objets solides et durs.

Mais apparemment, le fait de penser à ce genre de choses brouille quelque peu les pistes. Elle bouleverse nos conclusions habituelles - elle remet en question notre expérience normale.

Les deux parties de ce débat s'accordent en fait sur le fait que l'esprit et la matière sont étroitement liés. Ils affirment tous deux que l'un découle de l'autre - ce n'est pas là que réside le désaccord. Les matérialistes pourraient insister sur le fait que nous avons largement démontré que la conscience est une propriété émergente du cerveau. En manipulant les cerveaux, nous pouvons directement affecter les états mentaux. Les idéalistes répondront : "tout est dans ton esprit, mec - même tes expériences et tes idées sur les cerveaux".

Bernardo déclare : "nous ne connaissons pas - et fondamentalement nous ne pouvons pas connaître la matière avec autant d'assurance que nous connaissons l'esprit". Il entend par là que notre expérience d'un monde matériel est une déduction basée sur notre interprétation des données sensorielles et de la mémoire. C'est ce qu'il appelle "l'écran de la perception". Ce qui ressemble beaucoup à l'interface mentale de perception de Hoffman.

"Nous ne pouvons pas connaître la matière avec autant d'assurance que nous connaissons l'esprit, parce que notre connaissance du monde ne commence pas avec la matière mais avec la perception". Il s'agit fondamentalement d'un idéalisme épistémologique.

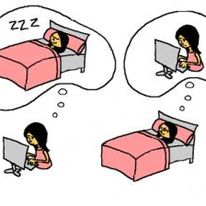

Les expériences que nous avons du monde nous semblent si réelles que nous les confondons avec la vérité. Lorsque je me cogne l'orteil, la douleur que je ressens est un fait solide et dur. Lorsque je regarde le ciel, le bleu que je vois semble se produire "là-bas". Nous pouvons faire des prédictions précises sur le monde extérieur, nous pouvons naviguer efficacement dans ce monde. Tout cela donne l'impression que nous percevons directement la réalité. Nous oublions que ce que nous percevons directement est une expérience mentale.

De la même manière que nous ne nous rendons généralement pas compte que nous rêvons lorsque nous rêvons, les rêves semblent réels.

Le matérialisme consiste essentiellement à ne pas comprendre que le monde matériel est une construction cognitive. Nous interprétons les données sensorielles, nous ne percevons pas directement la réalité telle qu'elle est. La matière est une déduction, donc mentale - l'esprit est la seule certitude.

La dernière phrase, "l'esprit est la seule certitude", est tout à fait conforme au "cogito ergo sum" de Descartes. L'affirmation de Descartes étant la finalité du "doute radical" - sa conclusion étant que la seule chose dont nous pouvons être certains est l'expérience mentale.

Quoi qu'il en soit, l'idéaliste conclut que ce que nous appelons le "monde physique" est plus précisément défini comme le "contenu de la conscience".

Il est évident que tout ce que nous pouvons percevoir de la réalité est nécessairement un état mental. Mais si un idéaliste a raison d'affirmer que nous ne pouvons pas être certains que le monde est physique, sur quelle base pouvons-nous affirmer que la totalité de l'existence est exclusivement mentale ?

Bernardo semble l'affirmer. Il croit en un "esprit universel" comme fondement de tout être. Selon lui, l'esprit universel est le "primitif ontologique" (parce qu'il est philosophe), ce qui signifie simplement : ce dont tout le reste découle, la source de tout le reste.

Il postule que la réalité est fondamentalement l'expression de cet esprit universel, et que notre expérience subjective, nos esprits personnels sont comme de petites poches de conscience. Il pense que l'esprit universel unique s'est en quelque sorte dissocié et que cette dissociation ou ségrégation est responsable de toutes les identités apparemment séparées qui existent dans le monde.

Malheureusement, comme je l'ai déjà dit, je ne vois pas pourquoi - je ne vois pas les étapes logiques ou les raisons qui mènent à sa conclusion.

Pour étayer son idée selon laquelle notre expérience subjective est une bulle dissociée de l'esprit universel, il évoque la maladie mentale connue sous le nom de "trouble dissociatif de l'identité" (TDI). Ce qui est tout simplement triste et troublant, et ne constitue en aucun cas un argument en faveur de son hypothèse - si ce n'est pour dire "hey ! ces choses-là arrivent, ce n'est pas impossible".

Quant aux principales raisons pour lesquelles nous devrions croire que la réalité fondamentale est nécessairement mentale, il faudra le lui demander. Comme je l'ai dit : je ne comprends pas - et j'abandonne.

Mais terminons par quelques-uns des arguments que j'ai réussi à saisir :

- Si nous n'étions pas conscients, nous ne pourrions même pas déduire qu'il existe un monde matériel.

Notre expérience du monde est un état mental, et le monde matériel n'est qu'une déduction au sein de cet état mental. Nous pouvons donc dire des choses comme : l'état mental est fondamental, le monde matériel est une déduction secondaire. À ce stade, nous sommes invités à commettre l'une des deux erreurs suivantes. Le sophisme définitoire, où nous avons utilisé le mot "fondamental" pour décrire notre expérience mentale du monde - par conséquent, "Gotcha !", la réalité fondamentale est mentale ? Ou le sophisme de la composition, où nous concluons que toute la réalité est mentale parce que la seule partie de la réalité dont je peux être certain est mentale.

- Si nous acceptons la primauté de l'état mental et que les objets dont nous faisons l'expérience sont des constructions mentales, prétendre que la conscience émerge de la matière est une supposition contraire à la réalité.

Affirmer que la conscience est une propriété émergente du cerveau est une erreur, car nous ne pouvons être certains que de la conscience, c'est-à-dire cogito ergo sum. Le cerveau n'est qu'une partie du contenu conceptuel de la conscience. Les scientifiques qui démontrent que la conscience humaine est étroitement liée au cerveau humain passent à côté de ce point important.

Le principal problème de cet argument est qu'il n'est pas un argument en faveur de quoi que ce soit - il s'agit au mieux d'un argument contre le camp adverse. Malheureusement, même si nous parvenons à prouver de manière concluante que toutes les affirmations matérialistes sont fausses, cela ne prouve en rien que l'idéalisme est correct ou même possible. Par exemple, si vous pouvez prouver que l'abiogenèse et la théorie de l'évolution sont fausses, nous ne pouvons toujours pas être certains que Dieu l'a fait.

- Le principe de l'observateur (en physique quantique), qui concerne la manière dont une situation donnée est affectée lorsque nous interagissons avec elle - par le biais d'une mesure ou d'une perception.

Bernardo présente cela comme un exemple d'un événement étrange de "l'esprit sur la matière" - comme le pouvoir de la conscience de transformer la réalité matérielle. Mais il s'agit là d'une interprétation plutôt personnelle de sa part, qui n'est en aucun cas représentative du consensus scientifique. Et même si nous acceptons sa définition comme correcte, nous devrions également prendre en compte toutes les démonstrations scientifiques contraires. Par exemple, le fait que l'expérience consciente dépende de l'état du cerveau, c'est-à-dire que la conscience est déterminée par la matière.

Bernardo s'appuie également sur les archétypes jungiens. Il s'agit de la façon dont notre conscience collective se manifeste dans le monde matériel. Par exemple, nos croyances en des concepts tels que l'argent ou les droits de l'homme deviennent des objets concrets dans le monde réel, sous forme de billets de banque ou de lois. Faites-en ce que vous voulez.

C'est alors que le Dr Kastrup se sent suffisamment à l'aise, ayant montré qu'il n'est pas dupe, pour conclure par quelques déclarations religieuses qu'il juge appropriées. Répétons-les donc ici :

"Le monde est la pensée de Dieu" Thomas d'Aquin & "Voir Dieu, c'est être Dieu" Sri Ramana Maharshi.

Une réponse à "Idealism

-

UteS

Bonjour Douglas, excellent sujet, merci.

L'idée d'introduire Dieu comme une sorte d'explication à tout semble un peu audacieuse. Peut-être est-ce dû à notre mode de pensée autoritaire ?

Albert Einstein : "L'espace et le temps sont des modes de pensée et non des conditions de vie.

Que savons-nous des circonstances de notre vie sans pensée, sans connaissance, sans théorie à leur sujet ? N'est-ce pas seulement par la pensée (et ce que Krishnamurti appelait le devenir) que l'impression de temps et d'espace apparaît sous la forme d'un mouvement vers un but, d'une planification, d'un passé et d'un futur, d'un ici à un là ?

Nous n'avons pas créé nous-mêmes notre mode de conscience et de pensée (comment le pourrions-nous ?), mais il s'est développé au fil du temps, comme le reste de la nature. Il s'agit d'un phénomène qui, comme tout le reste, semble surgir du néant.

Laisser un commentaire